Tel Dan

No site in Israel combines all the elements that Tel Dan displays: a delightful walk through the forest along the rushing waters of a source for the Jordan River, a high place notorious in the Old Testament, an example of a gateway containing both a judgment seat and massebot, and a Middle Bronze gate from the time of Abraham. Such a location stirs both mind and soul. Take the time to experience all of the site and to learn about every one of its fascinating aspects. Being part of a nature preserve, Tel Dan (Tell al-Qadi or Tell el-Khaddi) offers a delightful outing.

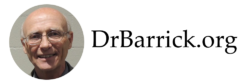

From the foothills of nearby Mt. Hermon, Tel Dan appears as part of a dark green patch of the wooded banks of the Jordan River and its springs. Another beautiful location sits nearby — Caesarea Philippi (which this blog will soon report). The Huleh Valley within which Tel Dan lies comprises a large portion of Upper Galilee with its neighboring mountains and hills. The area’s rich history, beautiful landscape, lush farmland, hiking trails, and bountiful wildlife preserve place it among the most attractive tourist destinations in Israel.

Passing through the area in 1863, Henry Baker Tristram describes Tel Dan in glowing words:

A ride of three miles from the bridge brought us to Tell Kady (“the mound of the judge”), which thus, in the significance of its name, still preserves the ancient Dan (“judge”). On the higher part of the mound to the south, tradition places the temple of the golden calf, and ruined foundations can still be traced. Nature’s gifts are here poured forth in lavish profusion, but man has deserted it. Yet it would be difficult to find a more lovely situation than this, where “the men of Laish dwelt quiet and secure.” “We have seen the land, and behold it is very good.… A place where there is no want of anything that is in the earth” (Judg. 18:9, 10). At the edge of the wide plain, below a long succession of olive-yards and oak-glades which slope down from Banias, rises an artificial-looking mound of limestone rock, flat-topped, eighty feet high, and half a mile in diameter. Its western side is covered with an almost impenetrable thicket of reeds, oaks, and oleanders, which entirely conceal the shapeless ruins, and are nurtured by “the lower springs” of Jordan; a wonderful fountain like a large bubbling basin, the largest spring in Syria, and said to be the largest single fountain in the world, where the drainage of the southern side of Hermon, pent up between a soft and a hard stratum, seems to have found a collective exit. Full-grown at birth, at once larger than the Hasbany which it joins, the river dashes through an oleander thicket.

— H. B. Tristram, The Land of Israel: A Journal of Travels in Palestine, Undertaken with Special Reference to Its Physical Character, 3rd ed. (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1876), 572

The bridge Tristram mentions was the Jisr el-Ghujar crossing the main stream of the Jordan River half-way between Abel-beth-maacah (due west of Tel Dan) and Tel Dan. Those 19th-century travelers next made the brief ascent to Banias (Caesarea-Philippi) to the east.

One of the modern information signs along the footpath to Tel Dan explains that the spring at Tel Dan (one of three principal sources for the Jordan River) produces 250 million cubic meters of water per year. Such a voluminous and consistent water supply made the area quite suitable for habitation throughout the site’s history. It remains a significant source of water in the modern nation of Israel, providing for irrigation in the upper valley of the Jordan, supply to the Sea of Galilee, and ultimately irrigation in the lower valley of the Jordan.

Biblical Occurrences

Dan’s earliest mention in the biblical text occurs in Genesis 14:14 in the time of Abraham. The text stirs a debate over the apparent anachronism (identifying Laish as Dan before the Danite migration described in Judges 18) and whether a proper understanding might involve what some refer to as “inspired textual updating.” Robert Dick Wilson (renowned for his mastery of Ancient Near Eastern languages and history) offered the following solution, allowing both names to exist simultaneously throughout the city’s history: “Laish may have been written with the signs la and ish in cuneiform and might be read as Laish, or after the conquest by the Danites as Dan.”[1] As Wilson points out, cities and countries mentioned in the Old Testament sometimes possess two different names (e.g., Mizraim and Ham for Egypt, as well as Hebron known also as Kiriath-Arba).[2]

The next appearance of Dan in the Bible comes in Joshua 19:47 recounting the Danites’ conquest of Leshem and their renaming the city Dan. Another form of the older name, Laish, occurs in Judges 18:7, 14, 27 giving a more extended account of the Danites’ relocating their tribal center to Laish (Dan, v. 29). Thereafter, mention of Dan can be found in 1 Kings 12:27–30 (Jeroboam I, 930–909 BC, setting up the golden calf worship in Dan and Bethel); 15:20 (parallel to 2 Chronicles 16:4; Syria’s Ben-Hadad I, ca. 895–860 BC, conquering Dan during the reign of Baasha, 908–886 BC); and, 2 Kings 10:29 (Jehu, 841–814 BC, failing to put a stop to the golden calf worship at Dan and Bethel). The biblical phrase “from Dan to Beersheba” (Judges 20:1; 1 Samuel 3:20; 2 Samuel 3:10; 17:11; 24:2, 15; 1 Kings 4:25; 1 Chronicles 21:2; 2 Chronicles 30:5) describes the north-to-south extent of the land of Israel (a distance of approximately 170 miles). Texts like Jeremiah 4:15 appear to use “Dan” as a reference to the tribe as a whole and its territory, rather than specifying the city of Dan alone.

Historical Background

Archaeological evidence indicates that Laish was founded around 2700 BC and flourished until about 2300 BC before falling into ruins and remaining unoccupied until around 2000 BC. At that time the builders of the city surrounded it with a massive earthen rampart (similar to that at Hazor). A large, Middle Bronze Age, triple arch, mud-brick gate provides us with one of the earliest arched city gateways in the world. It stood approximately forty feet above the surrounding area outside the city. Stone steps led from the lower ground on the eastern side of the city up to the gate and then down from the gate into the city itself. Egyptian execration texts and the Mari letters both mention Laish as a town in Canaan in the 19th–18th centuries BC. In the Middle Bronze Age (2200–1550 BC) during which Abraham lived, the city probably covered a little over thirty acres. According to Genesis 14, Abraham pursued the alliance of kings who had captured his nephew Lot when they raided Sodom and Gomorrah. He and his 318 armed men may have spent a night at Laish/Dan before going on to Hobah where they caught up with the kings and recovered their loot as well as rescuing Lot. Although archaeologists currently date the gate to the mid-18th century BC, it is possible Abraham entered the city through an earlier gate at the same location (or, if the dating is a little off, he might have seen this very gate). The biblical text does not mention Abraham visiting Laish on his return. However, he probably retraced his steps before he traveled south to pay a tithe of the recovered loot to Melchizedek, king of Salem (= Jerusalem).

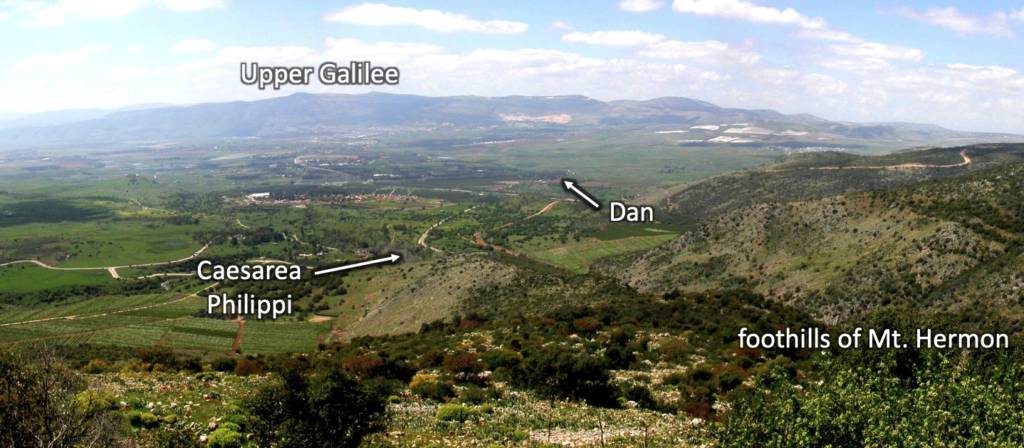

The Egyptian Pharaoh Thutmose III (1479–1425 BC) includes Laish in his list of cities he conquered in Canaan during his campaign of 1468 BC. The list appears on the temple walls at Karnak in Egypt with the cartouches for the names of Hazor and Laish adjacent to one another (see the photo below).

In 930 BC the nation of Israel divided into two kingdoms: the Northern Kingdom (Israel) and the Southern Kingdom (Judah; cf. 1 Kings 12:16–33; 2 Chronicles 10:1–19). At his coronation in Shechem Rehoboam, Solomon’s son, refused to lighten his father’s heavy tax burden on the people. As a result, the ten northern tribes revolted and selected Jeroboam (Jeroboam I, 930–909 BC) as their king. In order to keep the inhabitants of the Northern Kingdom from going to Jerusalem for worship, Jeroboam established worship centers in Dan and Bethel, equipping them both with a golden calf idol and cultic installations.

Tiglath-pileser III (745–727 BC) conquered Dan around 743 BC (see 2 Kings 15:29) and made it part of a district under Assyrian domination. Danites were among the Israelites deported to Assyria after Sargon II (721–705 BC) captured Samaria in 722/721 BC.

When Josiah (640–609 BC) was king of Judah, he restored the borders of Israel back to the description of “from Dan to Beersheba” (see 2 Kings 23:19–20 for the implication). A city gate dates to this period of Dan’s history. A Phoenician inscription on a pottery sherd found in 1968 at the level of the upper gate reads, לבעלפלט, “belonging to Ba’alpelet” — the name means “may Ba’al rescue”; an indication that the worship of Ba’al continued. The city later fell again to the Babylonians under Nebuchadnezzar (ca. 589 BC; see Jeremiah 4:14–18).

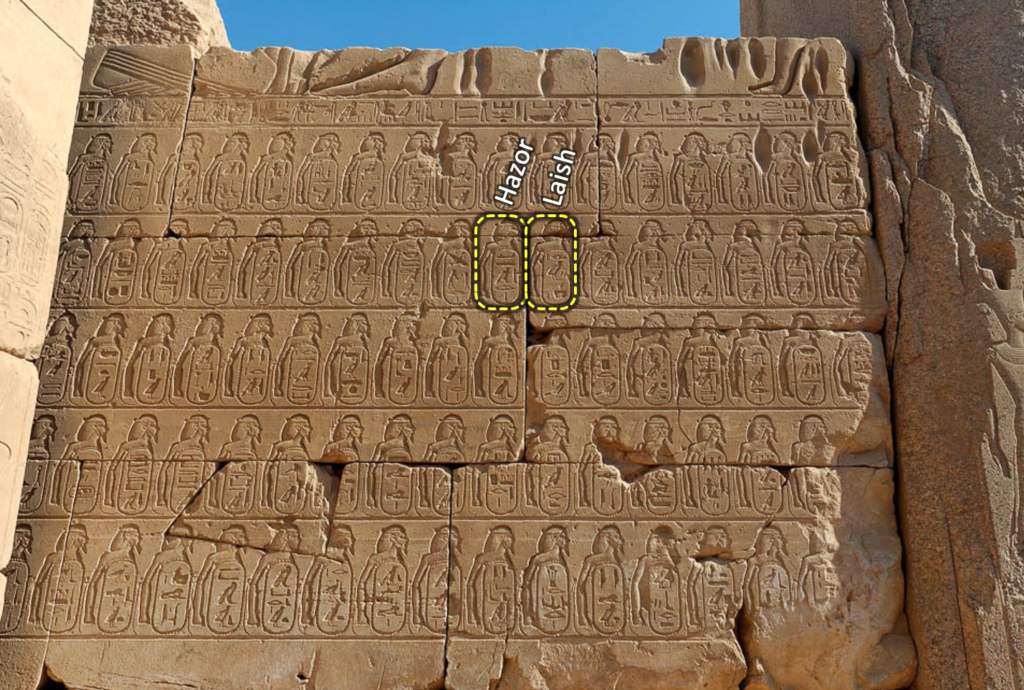

During the Hellenistic (332–37 BC), Roman (37 BC–AD 324), and Byzantine (324–640 AD) periods, Dan was rebuilt and reoccupied. From among the artifacts recovered from those periods is a Greek and Aramaic inscription reading, “To the god who is in Dan, Zoilos made a vow” (“ΘΕΩΙ ΤΩΙ ΕΝ ΔΑΝΟΙΣ ΖΩΙΛΟΣ ΕΥΧΗΝ”; see photo below — the Aramaic line below the Greek reads, [בדן] נדר זילס לא[להא], “[in Dan] Zoilos vowed to G[od]”). This inscription was recovered in the area of the great altar in 1976.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations at Tel Dan commenced in 1966 under the direction of Avraham Biran (Department of Antiquities and Museums, Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion). Archaeologists discovered evidence of an early settlement in the Pottery Neolithic Period (ca. 5000 BC). They also uncovered floors, walls, and pottery from the Early Bronze II (ca. 2700–2600 BC) and evidence that the city comprised about 50 acres during that time period. The great rampart and Middle Bronze gate mentioned above were among the discoveries dating from about 2000 BC. According to Biran, “It is estimated that in order to build the ramparts about 800,000 tons of material had to be used, a task which would require a thousand workers three years to complete.”[3] The Middle Bronze gate in the southeast corner of the city wall consisted of 47 courses of mud brick that were originally covered with a white lime and calcite plaster (remnants of the plaster were found in the joints between the courses). The main entry way measures eight feet across and ten feet high. The gate must have provided an imposing facade. Its three arches divide the gate structure into four chambers. Despite its impressive appearance, the gate soon developed structural issues and was buried to incorporate it into the great earthen rampart surrounding the city. That burial preserved the structure up until its discovery in the 20th century.

The Late Bronze Age (1550–1150 BC) finds included Mycenaean and Cypriote imported ceramic pieces, cosmetic boxes inlaid with ivory, objects of gold, silver, and bronze, tombs, and the skeletal remains of forty-five people (including men, women, and children).

During Iron Age I–II (1200–586 BC) the site occupied its full 50 acres. Excavations provide evidence of a number of conquests, one of which was quite likely that by the Danites in the 13th–12th century BC. At that stratum in the tell many stone-lined pits appear, indicating a significant change in the occupiers of the site. The pits served for storing food. Another destruction took place in the 11th century BC leaving 2–3 feet of ash, burnt bricks, and shattered household vessels. Among the finds from the period of the Danite occupation were remnants of Philistine pottery.

Great Horned Altar

Among the discoveries at Tel Dan the most prominent biblically consists of the great horned altar constructed in the time of Jeroboam I (930–909 BC) for the worship of the golden calf. A metal frame depicting the shape of the altar has been erected on the altar’s platform. The size and shape was determined by means of one of the altar’s horns which had been found during excavation. The altar appears to have been enlarged and remodeled during the reigns of Ahab (874–853 BC) and Jeroboam II (793–753 BC). Connected with the altar is another platform on which the idol of the golden calf must have stood. The installation includes some storage rooms. A number of cult-related artifacts have been recovered in that area including “terracotta and faience (glazed earthenware) male and female figurines, incense stands, a miniature horned altar, and several bronzes, including a fine scepter and several incense-offering shovels.”[4]

Iron Age Gate and Fortification Wall

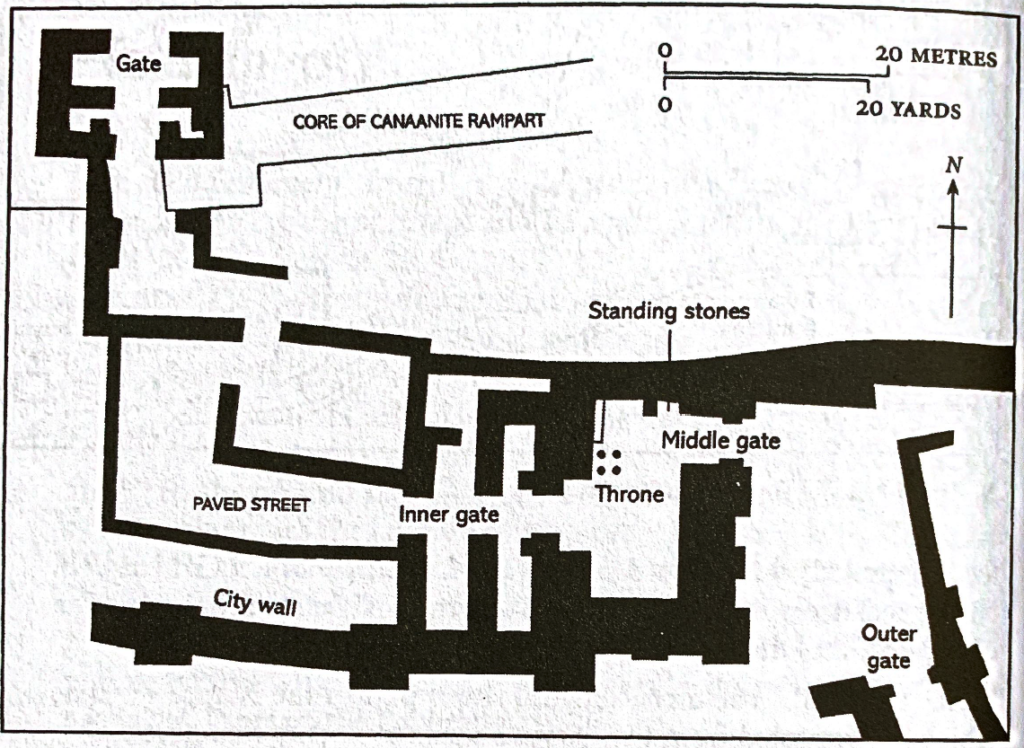

The 9th century BC city wall of Dan and gateways have also been excavated (see photos below). Biran describes this southern section as follows:

The establishment of a cult center at Dan called also for special security—remains of massive fortifications, a city wall, and a gate were uncovered at the S foot of the mound. In the 9th century B.C.E. a 4 m thick city wall and gate complex which included an outer gate with a large paved square were built. The gate has four chambers and a monumental paved entryway leading up to the top of the mound. Between the two gates is a stone-paved piazza, 19.5 × 19.4 m, with a bench for the elders and a canopied structure where the king may have sat …

— Avraham Biran, “Dan (Place),” in The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, ed. by David Noel Freedman et al. (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 2:15

The podium at Tel Dan’s Iron Age gate provides a superb example of the way the ancient peoples of the region conducted the judicial functions of a city’s rulers or elders (see Ruth 4:1–12 for but one of a number of examples within the biblical text). As with the podium set in the gate at Hazor, a cultic bamah (“high place”) with five massebot (standing stones) lies nearby (see photo below; cf. 2 Kings 23:8). One key element related to the podium consists of the carved (pomegranate form) stone bases for the canopy that was erected over the podium to protect the seated ruler/judge from the hot sun or rain. In the photo above, the wood posts and framework are a modern reconstruction for which only the carved stones at the base of each post were discovered during excavation. (Keep these pomegranate-formed bases in mind for future blog posts that will return to this element.)

Cemetery

While digging a channel for an electric cable in 2004, a crew unearthed ancient remains a little over 100 yards north of Tel Dan. Among the finds were pottery fragments and burned bones. The discoveries consisted of burials of several individuals 15–20 years of age from the 7th–6th centuries BC, as well as one adult (over 30), and a few infants. Other artifacts included bronze bracelets, bronze and silver toggle pins, silver earrings, bronze and iron arrowheads, spear and javelin, and a variety of beads. Several tombs were discovered. Two jar burials were also found as well as a cremation burial. Some of the burials might date from the 10th–9th centuries BC. The finds are significant since no cemetery had previously been found throughout the decades of excavation at Tel Dan. For a fuller report, see the article by Hartal listed in “Recommended Resources” below.

Tel Dan Stele

In 1993, on the final day of the excavations season at Tel Dan, Avraham Biran and Gila Cook were making certain the site was ready for the off-season.

The team’s surveyor, Gila Cook, first noticed it. There, in secondary use in a wall, on the east side of the plaza, beneath an eighth-century B.C.E. destruction level, she saw a basalt stone protruding from the ground. As the rays of the afternoon sun glanced off this stone, Gila thought she saw letters on it and called Biran over. When he bent down to look at the stone, he exclaimed: “Oh, my God, we have an inscription!” The stone was easily removed and, when turned toward the sun, the letters sprang to life. In their words, “It was an unforgettable moment.”

— “‘David’ Found at Dan,” Biblical Archaeology Review 20, no. 2 (March/April 1994): 33.

In his superb volume on Hebrew inscriptions from Bible times, Shmuel Aḥituv offers the following translation of the Tel Dan Stele. Before the translation he provides a transcription of the Aramaic text in modern Hebrew letters and follows the translation with a technical commentary on the text.

1 [ ] and cut (a treaty) [

2 [ … ʿe ]l my father went up [against him when] he was fighting in Abe [l?

3 And my father lay down, he went to his [ancestors/(place of) eternity]. And the king of I[s-

4 rael entered previously in the land of my father. [And] Hadad made me myself king.

5 And Hadad went in front of me, [and] I departed from [the] seven [cities]

6 of my kingdom, and I slew [seven]ty kings, who harnessed thou[sands of chariots

7 and thousands of horsemen/horses. And [was killed Jo] ram son of [Ahab

8 king of Israel, and [was] killed [Aḥaz]yahu son of [Jehoram, king

9 of the House of David. And I set [their cities into ruins and turned

10 their land into [desolation. And I slew all of it and I settled there

11 other [people]. And as to the te[mple, I devoted it. And Jehu son of Omri ruled

12 over Is[rael and I laid

13 siege upon [—Shmuel Aḥituv, Echoes from the Past: Hebrew and Cognate Inscriptions from the Biblical Period, trans. by Anson Rainey (Jerusalem: Carta, 2008), 468

The most likely date for the stele has been set at 841–840 BC, although some (including Biran) argue for 796 BC. The main debate rages on over whether ביתדוד (bytdwd) in line 9 presents a clear mention of King David. For those who argue that the absence of the word divider found throughout the inscription indicates a single word as a name (e.g., “Bitdod”), we must point out the absence of the word divider in line 3 between “king of” and “Israel” ( מלךי[ש]ראל, mlky[s]r’l) — another example of the word divider not being used between two nouns in construct, especially in a proper name or title. “The house of David” (the best reading of the text) is a phrase used twenty times in the Hebrew Bible. The Tel Dan Stele is but one piece of archaeological evidence testifying to the existence of a historical King David. The a priori evidence of the Hebrew Bible’s historical accounts should be sufficient in and of themselves to demonstrate the historicity of King David. Denial of the testimony of the ancient text requires equally ancient and authentic records stating or demonstrating the contrary — a favorite argument cited by the aforementioned Robert Dick Wilson.

This inscription holds specific significance to the historical accuracy and integrity of the biblical text in regard to Hazael, Jehoram, and Ahaziah (2 Kings 8:1–9:27). As mentioned in my earlier post on Dibon in Jordan, the Tel Dan Stele joins with two other inscriptions from the same basic period of time affirming the biblical record (the Mesha/Moab Inscription and the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III).

Recommended Resources

- Aḥituv, Shmuel. Echoes from the Past: Hebrew and Cognate Inscriptions from the Biblical Period, trans. by Anson Rainey. Jerusalem: Carta, 2008. Appendix 1, “The Tel Dan Inscription.” 467–73. (Includes a bibliography of significant works on the Tel Dan Stele.)

- Biran, Avraham. “Dan (Place).” In The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, 6 vols., ed. by David Noel Freedman et al. New York: Doubleday, 1992. 2:12–17.

- Biran, Avraham. “Sacred Spaces: Of standing stones, high places and cult objects at Tel Dan.” Biblical Archaeology Review 24, no. 5 (September/October 1998): 38–41, 44–45, 70.

- “‘David’ Found at Dan.” Biblical Archaeology Review 20, no. 2 (March/April 1994): 26, 28, 30–31, 33, 35–36, 39. (A full listing of inscriptions found at Tel Dan.)

- DeSilva, David. “Tel Dan: Sacred City of the Northern Kingdom.” 2017. Faithlife Logos Bible Software. Video. [11:00]

- Dever, William G. “Palaces and Temples in Canaan and Ancient Israel.” In Civilizations of the Ancient Near East, 4 vols. in 2, ed. by Jack M. Sasson et al. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2000. 1:605–14.

- Hartal, Moshe. “Tel Dan (North).” Hadashot Arkheologiyot 118 (2006).

- Kaiser, Walter C., Jr., and Paul D. Wegner. A History of Israel from the Bronze Age through the Jewish Wars, rev. ed. Nashville, TN: B&H Academic, 2016. (Pp. 8–9, 352–53, and 491 discuss the significance of the Tel Dan Stele.)

- Laughlin, John C. H. “The Remarkable Discoveries at Tel Dan.” Biblical Archaeology Review 7, no. 5 (September/October 1981): 20–37. (A detailed description and discussion of the Middle Bronze Gate.)

- Mazar, Amihai. “The Fortification of Cities in the Ancient Near East.” In Civilizations of the Ancient Near East, 4 vols. in 2, ed. by Jack M. Sasson et al. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2000. 3:1523–37.

- Muhly, James D. “Mycenaeans Were There Before the Israelites: Excavating the Dan Tomb.” Biblical Archaeology Review 31, no. 5 (September/October 2005): 44, 46–51.

- Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome. The Holy Land, 5th ed. rev. and expanded. Oxford Archaeological Guide. Oxford, Eng.: Oxford University Press, 2008. (Pp. 500–504)

- Price, Randall, with H. Wayne House. Zondervan Handbook of Biblical Archaeology. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2017. (Pp. 117–23 give a description of the Tel Dan Stele and its significance in the minimalist vs. maximalist debate over the historical existence of King David.)

- Sergio and Rhoda in Israel. “Tel Dan and the 4,000 Year Old Canaanite Gate.” Season 1, Episode 18. August 27, 2017. Video. [10.14]

Footnotes

[1] Robert Dick Wilson, A Scientific Investigation of the Old Testament, rev. by Edward J. Young (Chicago: Moody Press, 1959), 135. In Akkadian la iñänû means “poor, powerless, dependent”; A. Leo Oppenheim and Erica Reiner, eds., The Assyrian Dictionary: I and J, vol. 7 of The Assyrian Dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, ed. by Ignace J. Gelb, Benno Landsberger, and A. Leo Oppenheim (Chicago: Oriental Institute, 1960), 222 (hereafter referred to as CAD). la is often used as the first element of proper names in Akkadian and also may act as a preposition meaning “from”; A. Leo Oppenheim, Erica Reiner, and Robert D. Biggs, eds., The Assyrian Dictionary: L, vol. 9 of CAD (1973), 5. Interestingly, dannu (“solid, strong, reliable, fortified” is the opposite meaning to la iñänû; see A. Leo Oppenheim and Erica Reiner, eds., The Assyrian Dictionary: D, vol. 3 of CAD (1959), 92. According to René Labat, Manuel d’ Épigraphie Akkadienne, 5th ed. (Paris: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geunther, 1976), 147 (#322), 261, la6 is the same sign as dan as well as KAL (equivalent to dannu). In addition, the opposite meaning to iñ is the equivalent of danna (ibid., 107 [#166]), meaning “hardly, with difficulty” (CAD, 3:87). Therefore, Wilson’s suggestion that the same cuneiform signs could have been read both ways is perfectly legitimate. The Danites might have been attracted to Laish just because it may have also been known as Dannu, a name similar in sound to or reminiscent of their own ancestral tribal name.

[2] Wilson, A Scientific Investigation of the Old Testament, 138.

[3] Avraham Biran, “Dan (Place),” in The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, 6 vols., ed. by David Noel Freedman et al. (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 2:13. For additional description with detailed measurements, see Amihai Mazar, “The Fortification of Cities in the Ancient Near East,” in Civilizations of the Ancient Near East, 4 vols. in 2, ed. by Jack M. Sasson et al. (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2000), 3:1526.

[4] William G. Dever, “Palaces and Temples in Canaan and Ancient Israel,” in Civilizations of the Ancient Near East, 4 vols. in 2, ed. by Jack M. Sasson et al. (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2000), 1:610–11.