Due to the amount of information I desired to communicate about Beth-shean / Scythopolis, this site required two posts. Post #15 covered Old Testament Beth-Shean and this post covers New Testament Scythopolis.

Scythopolis

During the Greek period Beth-shean became known as Scythopolis (and, later, Nysa Scythopolis), one of the ten cities of the Decapolis. In fact, it became the chief city of the Decapolis even though it was the only one of those ten cities situated west of the Jordan River.

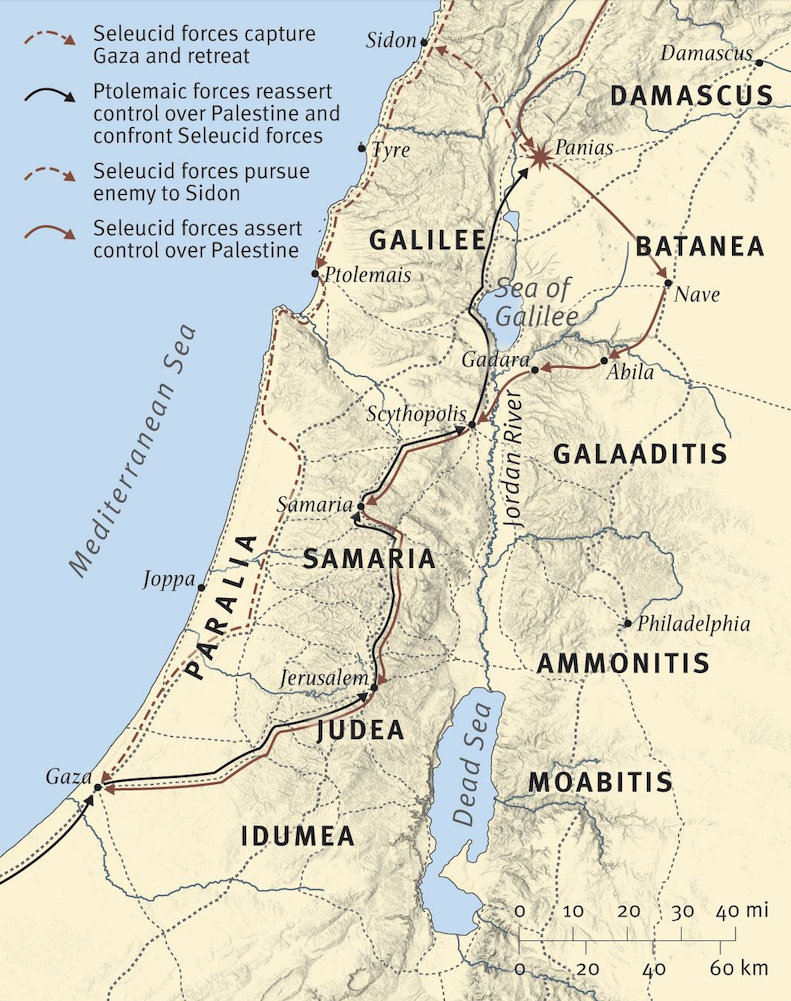

Archaeological evidence points to the site being reoccupied in the Hellenistic period (363–332 BC). Beth-shean was renamed Scythopolis in the time of Ptolemy II (Philadelphus, 285–246 BC). “Scythopolis” means “city of the Scythians,” perhaps a reference to a unit of Scythian cavalry serving in the army of Ptolemy II. In 163 BC, 1 Maccabees 5:52 mentions that Judas Maccabee brought his army across the Jordan River “into the broad plain by Beth-Shan” on their way back to Judah after his campaign in Gilead. A slightly different telling of this event occurs in 2 Maccabees 12:29–31 in which the author reports that Judas

marched against Scythopolis, … However, the Jews residing there bore solemn witness to the Scythopolitans’ goodwill toward them and to the kindness they had shown them in times of trouble. Accordingly, Judas and his men thanked the Scythopolitans, urging them to continue in the future to be friendly to our people.

During the reign of Antiochus VI (Epiphanes Dionysis, 145–142 BC), Jonathan Maccabee (160–143 BC) met the Seleucid general Tryphon at Beth-shean to do battle (1 Maccabees 12:39–53). But Tryphon tricked Jonathan into taking a small force with him to Ptolemais where he was slain. Later, John Hyrcanus (135–104 BC) retook the city. Then Pompey captured it by 63 BC. The Romans occupied the site from 63 BC until AD 324, initially rebuilding it in 57 BC and allowing it self-governance in 47 BC.

The Talmud has many references to the Jews of Beth-shan. Rabbi Simeon ben Lachish, ca. 350 A.D., said, “If paradise is situated in the land of Israel, its entrance is Beth-shan.”

— Henry O. Thompson, “Tell el-Husn — Biblical Beth-shan,” Biblical Archaeologist 30, no. 4 (Dec. 1967): 134

One synagogue in Scythopolis dates to AD 300 and the first Christian church made its appearance ca. 325. The city remained a cosmopolitan center with both Jews and Christians until it fell to Muslim invaders in 636. The Islamic conquest of the city is known in a number of sources as “the day of Beisan.” An earthquake (approximately 6.6 on the Richter scale) on January 18, 749 brought about the final destruction and abandonment of Beth-shean/Scythopolis. Four hundred years later crusaders captured the city and constructed a castle on the tell. But it fell to Saladin in 1183.

Modern note: The dead tree on the top of the tell was used for the final scene of “Jesus Christ Superstar” showing Judas hanging himself (see first photo below under “The New Testament City”).

The New Testament City

Scythopolis represents the best preserved Roman-Byzantine city in Israel (see the model of this period’s city inside the entrance to the Park). Since water was abundant in the Valley of Harod, the site enjoyed a long and prosperous existence. People moved from the upper city atop the hill down to the lower level in the valley. Later the city was called Nysa after Dionysius, the Greek god of drinking wine.

In 63 BC Roman general Pompey made it part of the Decapolis (ten cities designed as a source of Graeco-Roman influence). Beth-shean/Scythopolis was the only city of the Decapolis west of the Jordan River. After the 1st century BC, Jews could dwell safely in the lower city. In the 2nd century AD it became a textile center for the Roman Empire. The city reached its height of glory and influence in the Byzantine period (324–628). The destruction of the city in the 749 earthquake, earning its reputation as the “Pompeii of Israel.”

From the small Jewish community surviving the era of the Crusades, the first Hebrew book on the geography of the Holy Land was published (1322).

Although the New Testament does not mention Scythopolis itself, it does refer to the Decapolis (Matthew 4:25; Mark 5:20; 7:31). The ancient lists of these cities making up this group of ten cities differ from one another. However, the following seem to make the best grouping: Scythopolis (Beth-shean), Pella, Philadelphia (Amman), Gerasa (Jerash), Gadara, Hippos, Abila, Capitolias, Raphana (Raphon), and Dium — and some lists include Canata. The Decapolis consisted of cities boasting of their connection to Greek culture, institutions, and origin.[1]

Archaeological Notes

For the excavations of Scythopolis, the Roman theater (constructed late 2nd century to early 3rd century AD) was excavated by Shimon Applebaum and Avraham Negev (1960–1962). Yoram Tsafrir and Gideon Foerster of Hebrew University, as well as Gaby Mazor and Rachel Bar-Nathan of the Israel Antiquities Authority, have continued excavations at Scythopolis since 1986.

Before excavation, part of the theater was the only ruin protruding from the ground. Two bathhouses (one near the amphitheater) provided social gathering places similar to our modern health clubs. The model below reproduces the probable appearance of the complex. The third photo below explains how the citizens of Scythopolis used the bathhouse (start at upper right and move through the placards to the left — Hebrew order).

Amphitheater: Prior to modern archaeological excavations, robbers had taken away many of the amphitheater’s limestone seats. At one time the amphitheater seated around 7,000 spectators. It was used until the 6th century AD. A second amphitheater lies outside the national park. It was also Roman and dated from the 2nd century AD. Its first row of seats sat high enough above the floor to use the stage area (arena) for gladiatorial and hunting contests. Josephus says that some Jews captured in the defeat of the Zealots in AD 70 were forced to fight animals here — something that also occurred at Caesarea Philippi.

Public Market: A shrine was created within the semi-circular area of the public market. A mosaic of the goddess Nysa/Tyche(?) was discovered there.

Antonius Monument: This monument was erected at the intersection of the northern street where Valley Street turns north and Sylvanus Street continues east.

Monastery of Lady Mary: Before AD 567 this monastery was constructed at Scythopolis. It featured beautiful mosaics including a calendar mosaic in the main hall and twelve medallions in a room at the far end of the hall running from the entrance.

Recommended Resources

- Applebaum, Shimon. “The Roman Theatre of Scythopolis.” Scripta Classica Israelica 4 (1978): 77–105. (PDF download available.)

- Sergio and Rhoda. “Beit-Shean and Scythopolis — The Ancient Roman City.” Season 2, Episode 1. September 2, 2018. YouTube video. [11.50]

Footnotes

[1] Jean-Paul Rey-Coquais, “Decapolis,” in Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, 6 vols., ed. by David Noel Freedman et al. (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 2:116–21.