Rabbah Ammon / Amman Citadel

Today Amman serves as the capital of the Hashemite kingdom of Jordan. In ancient times it was known as Rabbah of the Ammonites. In the Hellenistic and Roman periods the city was named Philadelphia (honoring Ptolemy II Philadelphos, ruler of Egypt 285–247 BC). Philadelphia was the southernmost city of the Decapolis (see Matthew 4:25; Mark 5:20; 7:31

The Ammonites established their capital atop the hills along the Jabbok River valley (cf. Deuteronomy 2:37). King Og of Bashan slept on a large iron bed which ended up being kept in Rabbah Ammon (Deuteronomy 3:11). Archaeologists have exposed the Iron Age city wall surrounding the old Ammonite fortress.

From the heights where the Amman Citadel sits one can look down into the Jabbok valley at the Roman theater. Its semicircular plan includes three horizontal sections of seats. Coins excavated from the site indicate the theater was constructed around the middle of the 2nd century AD. On the acropolis Hadrian’s temple to Jupiter (Hadrian’s favorite deity, rather than Hermes, as some suggest) dominates the current scene.

Biblical history’s most significant event connected with the Amman Citadel involves the Israelite attack on Amman (also known as Rabbah Ammon) while King David remained in Jerusalem (2 Samuel 11:1; 1 Chronicles 20:1). At that time David caught sight of Bathsheba bathing and ended up in an illicit relationship and Bathsheba’s pregnancy (2 Samuel 11:2–5). While the Israelites besieged Rabbah Ammon, David gave Joab instructions to put Bathsheba’s husband Uriah in the front of the battle near the city wall, so he would be killed (2 Samuel 11:14–17).

When Joab and the Israelite army had captured the royal fortress of Rabbah Ammon, he sent for David to come and personally finish the conquest (2 Samuel 12:26–31). The Ammonite king’s crown was transferred to King David’s head (2 Samuel 12:30; 1 Chronicles 20:2–3).

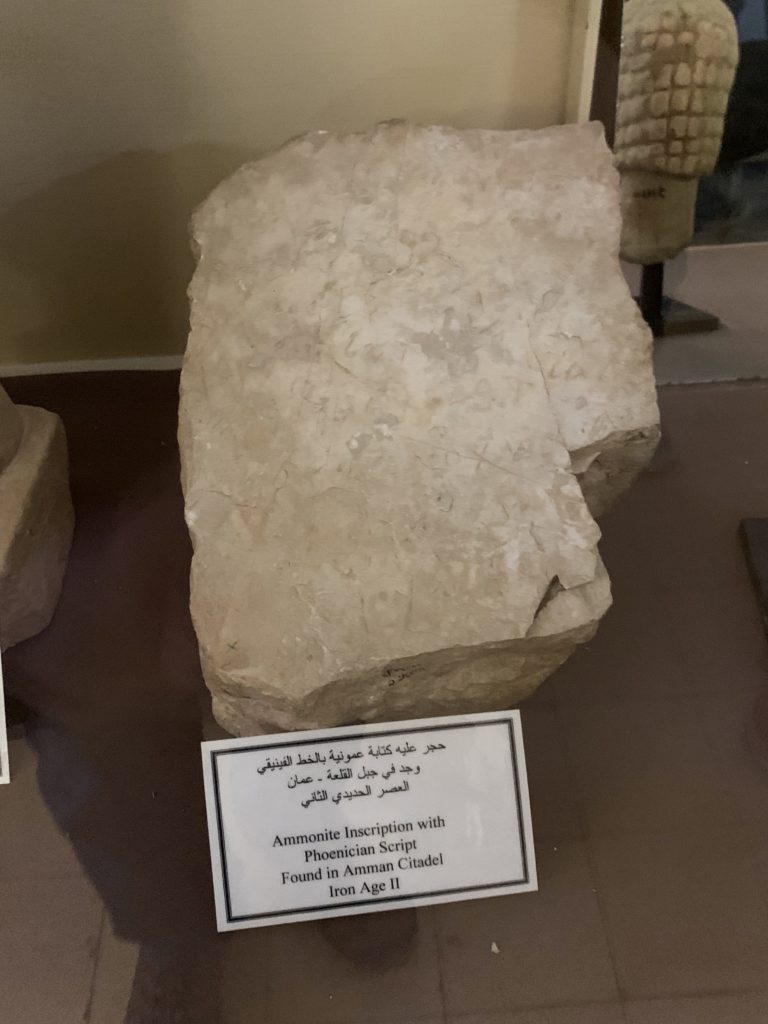

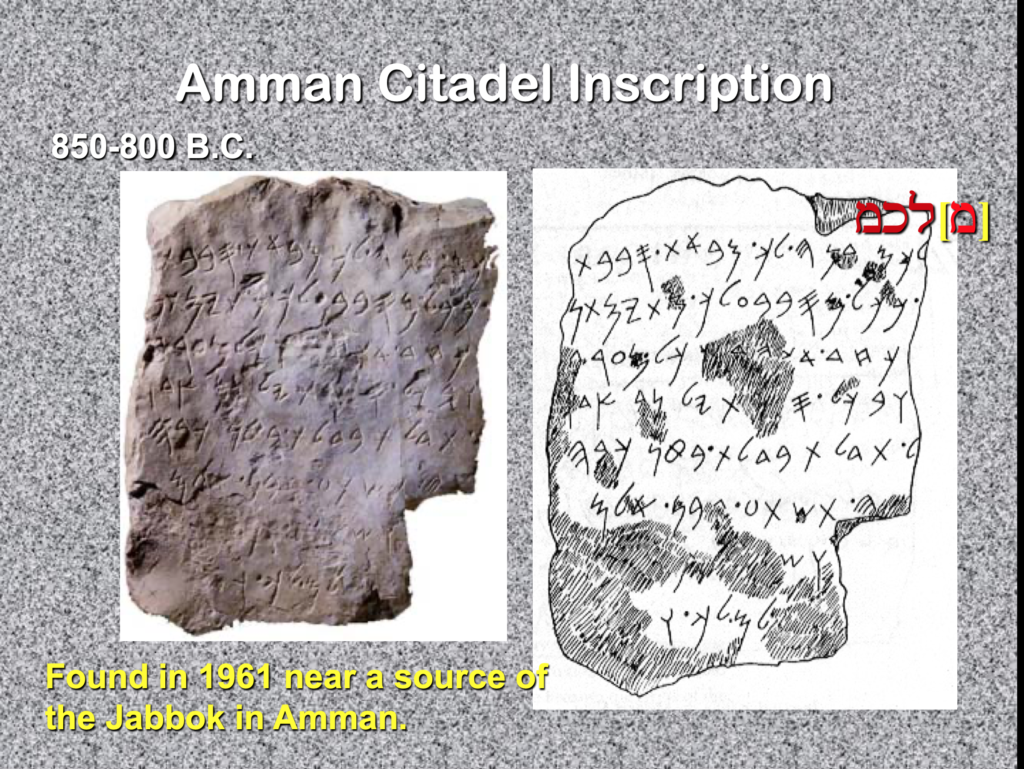

A museum near the Roman temple displays a variety of artifacts from the many periods of Amman’s ancient history. One inscription dates to the 9th-century BC. It’s but part of the total inscription referring to architectural structures. It might represent a dedicatory inscription for a temple to the Ammonite God Milcom, who is mentioned in the inscription; or it might be a royal record about the building of the city or its acropolis. Somebody in the past had repurposed it as a threshold for a door in a domestic structure—a piece was cut from it to allow it to fit better in its new context. It also demonstrates the close linguistic relationship between Moabite and Hebrew at that time.

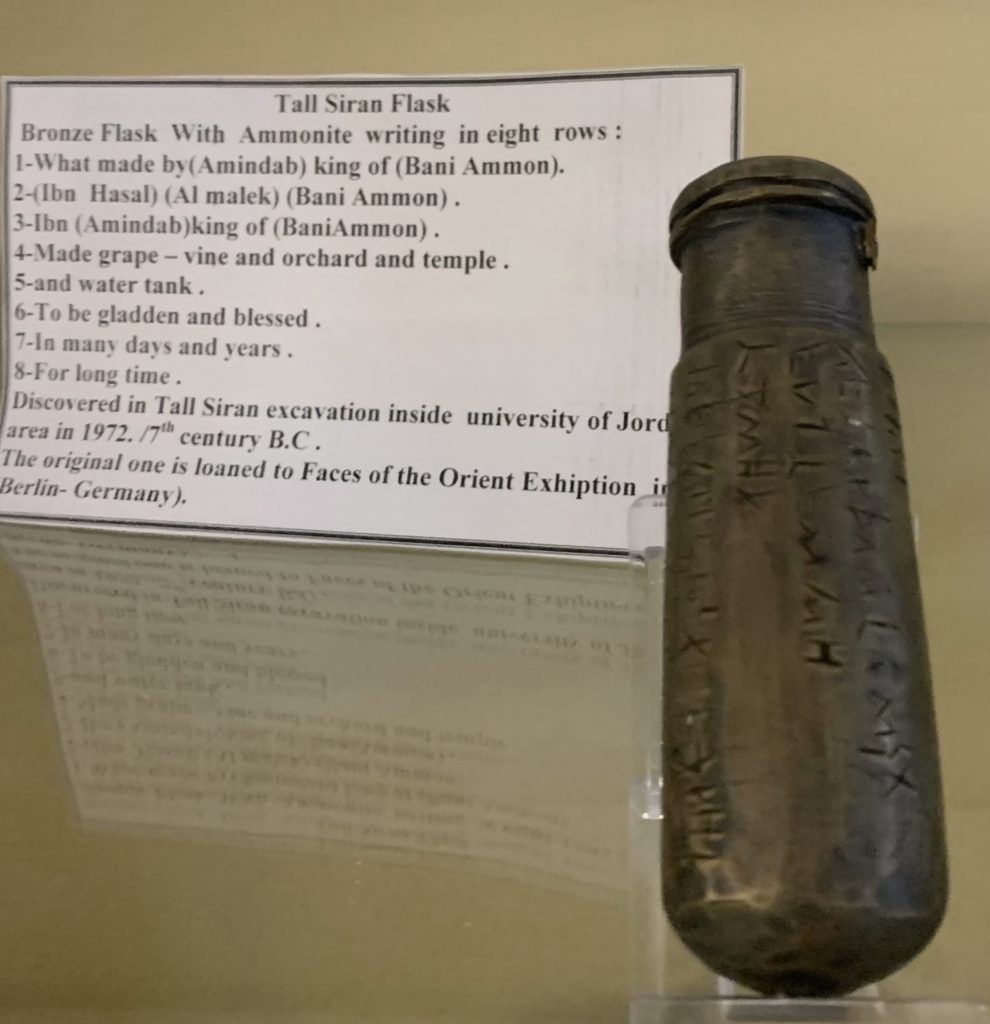

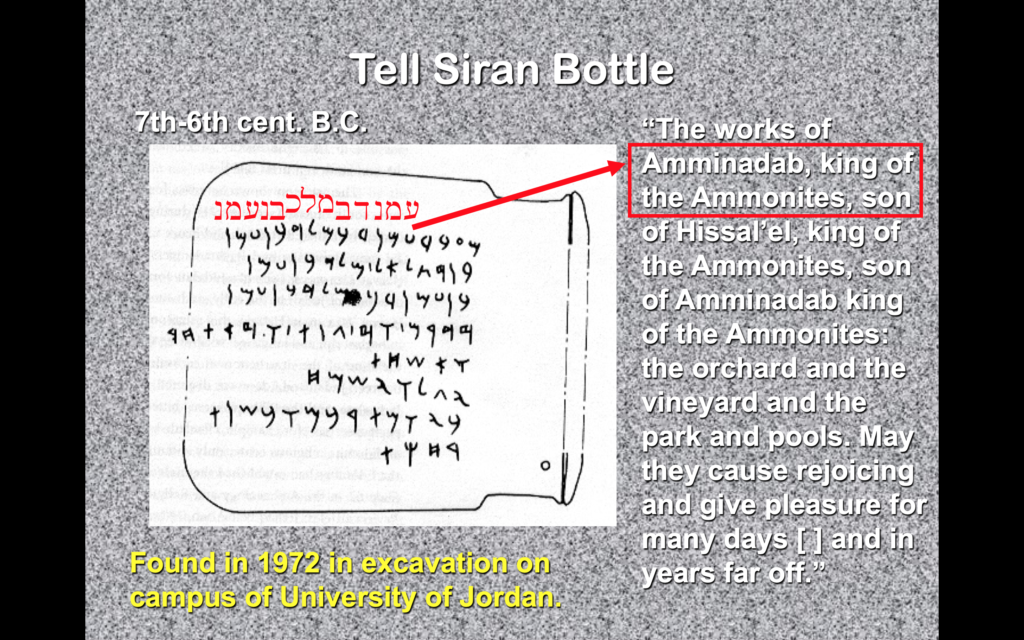

Another inscription occurs on the sides of a 4-inch high bronze bottle discovered at Tell Siran on the University of Jordan campus in Amman (near the hotel in which we stayed). This inscription describes vineyards, gardens, and cisterns belonging to Amminadab, the Ammonite king in the 7th century BC. This might be the same Amminadab mentioned in an inscription of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal dated to 687 BC.

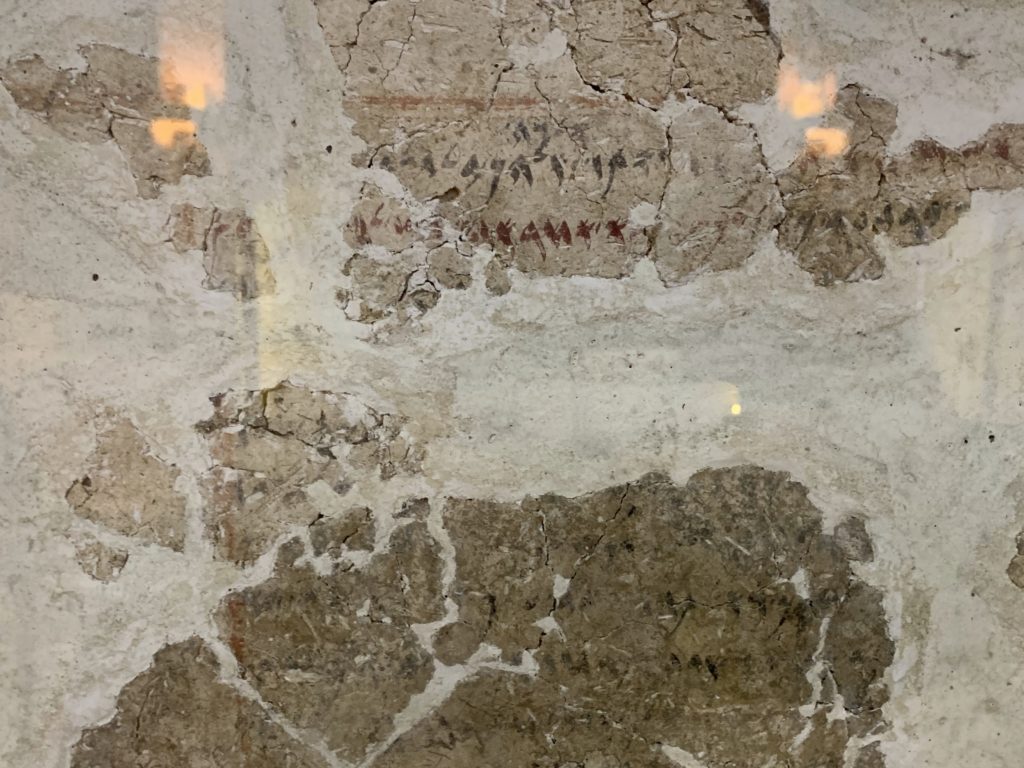

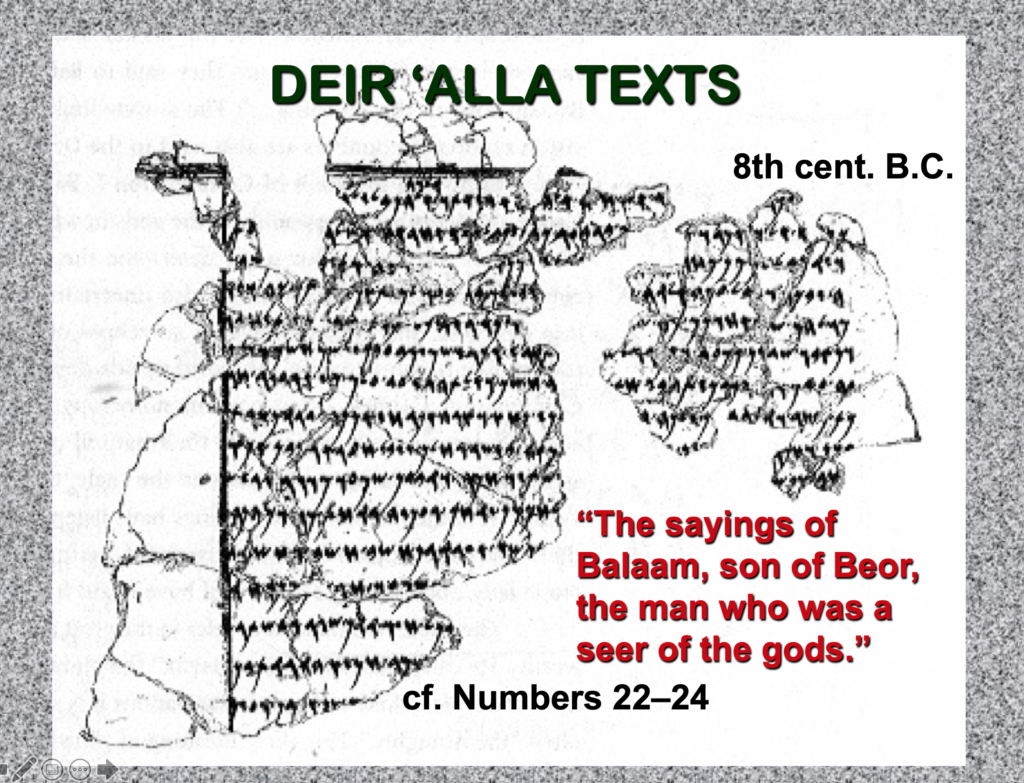

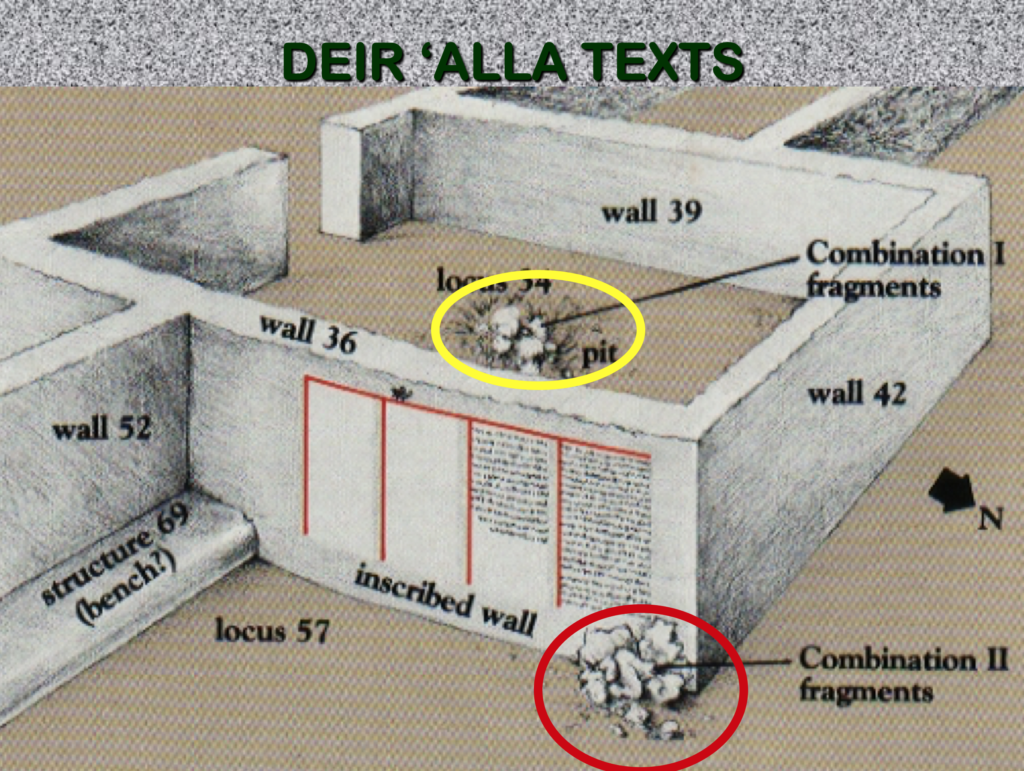

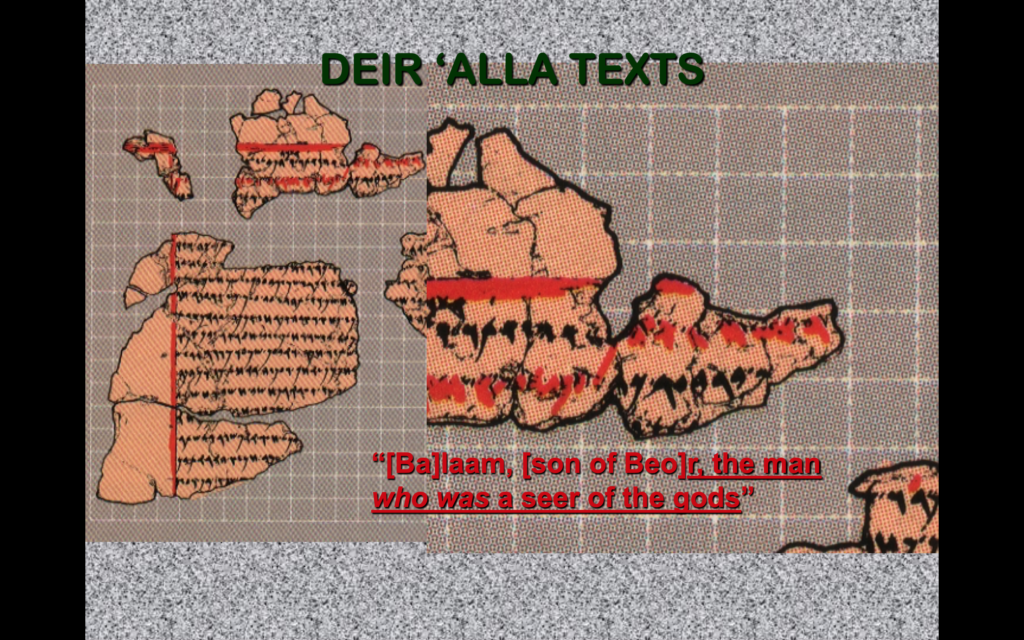

In addition, the museum presents a copy of the Baalam inscription found at Tell Deir ʿAlla (ancient Succoth, cf. Genesis 33:17; Judges 8:4–16) near where the Jabbok River canyon opens out into the Plain of Moab. Excavators at Deir ʿAlla discovered a cultic building of the 8th century BC with pieces of plaster fallen from the walls in an earthquake. Writing on the plaster pieces revealed an Aramaic inscription referring to Baalam of Beor. In fact, it uses similar words to those recorded in the introductions to his prophecies in Numbers 24:3–4. Red ink highlights some of the words—kind of like a “red letter edition.”

“[This is] the account of [Balaam, son of Be]or, who was a seer of the gods. The gods came to him in the night, and he saw a vision according to the oracle of El. Then they spoke to Ba[laa]m son of Beor: ‘This he will do … in the future(?) …’”