Peor

Geographical details in the account regarding Balaam in Numbers 22–24 provide information identifying the area where Israel camped east of the Jordan River before entering Canaan. When King Balak of Moab sent for Balaam to curse Israel, he went to meet him at Ar of Moab on the Arnon Gorge (Numbers 22:36; see Post #7 under Aroer). Balaam had traveled a long distance from Pethor/Pitru along the Euphrates River (Numbers 22:5). Balak took him first to Kiriath-huzoth (Numbers 22:39), perhaps the same as Kiriathaim (see Numbers 32:37). Balaam’s first sight of the Israelite encampment came at Bamoth-Baal (literally, “high places of Baal,” Numbers 22:41), which seems to have been a shrine on one of the high points of the Abarim range near Mt. Pisgah. Next, Balak took Balaam to Mt. Pisgah (Numbers 23:14) associated with Mt. Nebo. The third site to which Balak brought Balaam was Peor (Numbers 23:28), the next ridge northeast of Mt. Nebo on the Moab plateau.

From there Balaam could see the Israelites on the plains of Moab below at Abel-Shittim (see Post #1). While Israel camped at Abel-Shittim, they began practicing a despicable form of idolatrous prostitution and aligned themselves with the worship of Baal of Peor (Numbers 25:1–5). Such sexual sin soon manifested itself within the camp of Israel (Numbers 25:6–15).

During our tour of archaeological sites in Jordan we visited the site of ancient Peor. We found some excavation had taken place, but mainly just looting — evidenced by holes dug here and there in search of treasures. In fact, three local men had driven to the site and were sitting there as we walked atop the tell. One of the men noticed me looking through my small pair of binoculars and asked to look through them. Upon doing so, he offered a glass of spiced tea (marmaraya) to myself and Tim Sigler, who did the translating in Arabic. We both drank the tea and thanked them for their hospitality. The site needs excavating. Some of the lines for the city walls could be picked out without difficulty as well as several locations for additional buildings on nearby hills. We looked down at Tell el-Hamman (Abel-Shittim) and grieved over the sins of the Israelites at the time they were about to enter the Promised Land.

Heshbon

Our visit to Heshbon came at the end of an already long day including Medeba, Mt. Nebo, and Peor. We climbed up on the tell just as the sun was going down over the Jordanian hills. The Bible mentions Heshbon 38 times. The ancient city has been identified with the mound at Tell Hesban located on the Medeba Plain a little over 12 miles southwest of Amman and a little under 4 miles from Mt. Nebo. Andrews University excavated at the site 1968–1976. In 1978 Baptist Bible College of Pennsylvania excavated the Byzantine church at the site. These excavations did not discover any remains dating prior to 1200 BC.

Four potential solutions might be offered to the puzzling absence of remains from the time of Sihon’s Amorite capital (see Numbers 21:21–25; Deuteronomy 2:16–37; Judges 11:12–28): (1) Lack of evidence prior to 1200 BC could be the result of the seminomadic nature of the Amorites whereby they left behind very little physical evidence of their having been at the site. (2) The biblical record could be in error or anachronistic. (3) Another site might better fit the history and location of ancient Heshbon. (4) The archaeological evidence might require a more accurate and careful analysis. The final two of these four options are better than the previous two options.

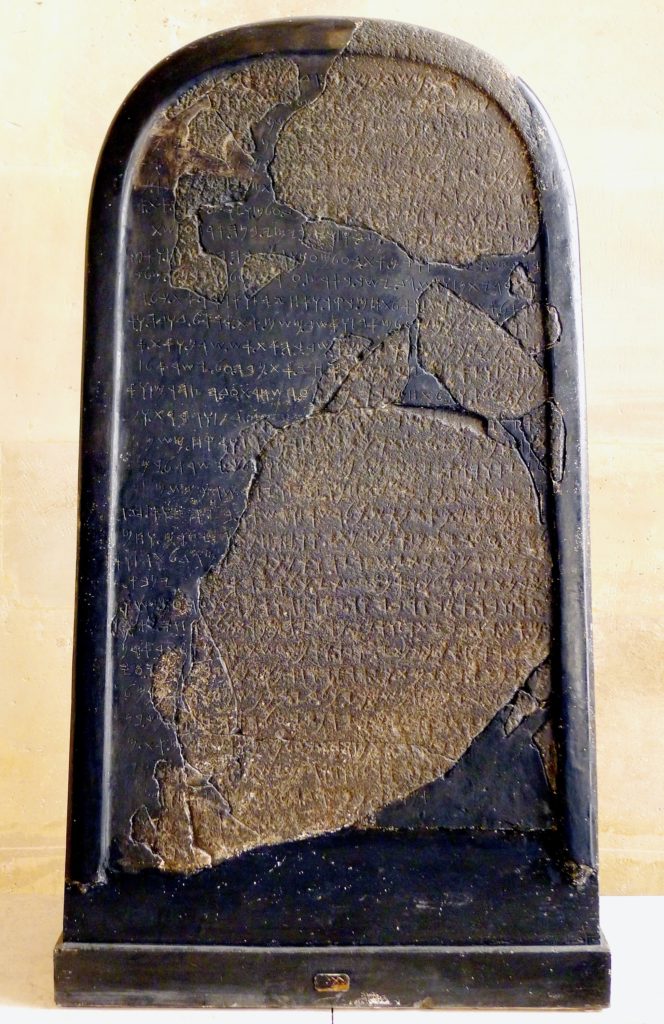

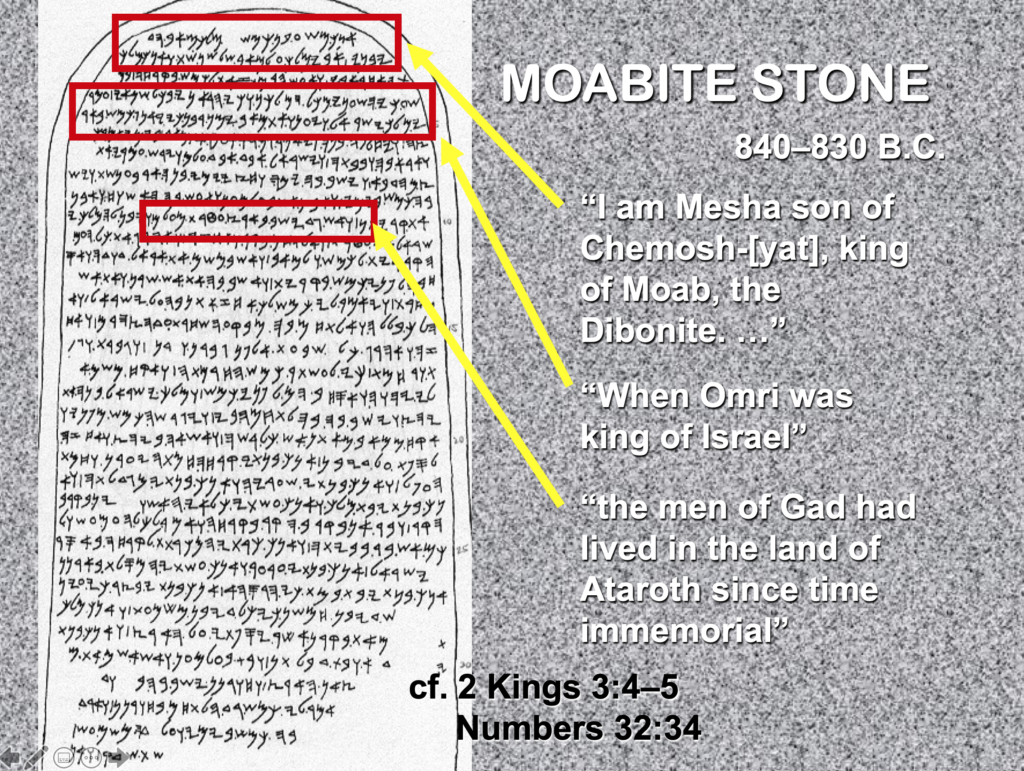

Dibon / Dibon-Gad

Dibon (the modern day village of Dhiban) was the capital city of the ancient Moabites. It sat just west of the King’s Highway (cf. Numbers 20:17; 21:22) about 40 miles south of Amman and about 2 miles north of the Arnon River. The Amorite king Sihon had taken Dibon from the Moabites before Israel took it from him. After Israel’s conquest of Moab, the tribe of Gad built up Dibon (Numbers 32:34; 33:45). The Mesha Inscription (also called the Moabite Stela or Moabite Stone) dating to 840–830 BC was found here in 1868. Before French archaeologists moved it to the Louvre in 1873, local men had broken it while attempting to get at a treasure they thought would be inside it. The following translation follows that of W. F. Albright:

I (am) Mesha, son of Chemosh-[ … ], king of Moab, the Dibonite — my father (had) reigned over Moab thirty years, and I reigned after my father, — (who) made this high place for Chemosh in Qarhoh [ … ] because he saved me from all the kings and caused me to triumph over all my adversaries. As for Omri, king of Israel, he humbled Moab many years, for Chemosh was angry at his land. And his son followed him and he also said, “I will humble Moab.” In my time he spoke (thus), but I have triumphed over him and over his house, while Israel hath perished forever! (Now) Omri had occupied the land of Medeba, and (Israel) had dwelt there in his time and half the time of his son (Ahab), forty years; but Chemosh dwelt there in my time. And I built Baal-meon, making a reservoir in it, …. Now the men of Gad had always dwelt in the land of Ataroth, and the king of Israel had built Ataroth for them; but I fought against the town and took it and slew all the people of the town as satiation for Chemosh and Moab. … And Chemosh said to me, “Go, take Nebo from Israel!” So I went by night and fought against it from the break of dawn until noon, taking it and slaying all, seven thousand men, boys, women, girls and maid-servants, for I had devoted them to destruction for (the god) Ashtar-Chemosh. And I took from there the [things] of Yahweh, dragging them before Chemosh. And the king of Israel had built Jahaz, and he dwelt there while he was fighting against me, but Chemosh drove him out before me. And I took from Moab two hundred men, all first class (warriors), and set them against Jahaz and took it in order to attach it to (the district of) Dibon. … I built Aroer, and I made the highway in the Arnon (valley); I built Beth-bamoth, for it had been destroyed; …

— in Ancient Near Eastern Texts, 3rd ed., ed. James B. Pritchard (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1969), 320–21

Compare the Mesha Stela text (the oldest extrabiblical text mentioning both Israel and Yahweh) with 2 Kings 3. Although Omri had succeeded in taking the region of Medeba (including Dibon) from Moab, Mesha rebelled after the death of Ahab. Kings Jehoram (of Israel) and Jehoshaphat (of Judah) joined forces to attack Mesha. During the battle Mesha sacrificed his eldest son on the city wall of Kir-hareseth. According to 2 Kings 3:27, it resulted in “great wrath against Israel, and they departed from him and returned to their own land” (NASU). On the one hand I think Mesha’s desperate act might have galvanized his army so that they counter-attacked the Israelite joint forces with such ferocity the Moabites succeeded in breaking the siege. On the other hand, the “great wrath” could have been God’s own rage by which He turned the Israelites’ near victory into the beginning of the Omride dynasty’s decline as judgment for their continued rebellion against Him. Meanwhile, according to the Mesha Stela, Mesha launched strikes against Israelite holdings north of the Arnon Gorge, devoted some kind of objects used in worshipping Yahweh to his god Chemosh, captured Jahaz, and established Dibon as his own capital. Even though Moab’s power waned at times in subsequent history, the prophets mention Dibon as one of the Moabites’ chief representative cities (Isaiah 15:2; Jeremiah 48:18).

A number of archaeologists conducted excavations at Dibon in the 1950s as well as a season in 1965. Carbon-14 dating and ceramic typology produced a date of approximately 850 BC for charred grain found during excavation. Extensive architectural remains can be dated to the time of Mesha’s rebuilding the city and making it his capital. Archaeological evidences recovered at Dibon indicate later Nabatean influence or rule as early as the first century BC. Trajan (AD 98–117) brought the city into the Roman province of Arabia in AD 106.