Petra

Match me such a marvel save in Eastern clime, a rose-red city half as old as time.

— John William Burgon

Biblical Connections

Preparing for a tour of Petra provides an opportunity to think about its biblical connections. Petra and its peoples’ histories begin with the history of Abraham’s descendants. When Abraham’s wife Sarah appeared to be barren, she gave him her handmaiden Hagar, so he could produce an heir (Genesis 16:1–14). Therefore, with Hagar Abraham produced Ishmael (Genesis 16:15–16). Thirteen years later, however, God promised Sarah would give birth to Isaac (Genesis 17), and about a year later, Sarah’s son was born (Genesis 21:1–8). This is the setting out of which the Nabataeans originated. Nebaioth, the father of the Nabataeans was the firstborn son of Ishmael (Genesis 25:13).

Prior to Ishmael’s birth, God told Hagar her son would be “a wild donkey of a man, / His hand will be against everyone, / And everyone’s hand will be against him; / And he will live to the east of his brothers” (Genesis 16:12 NASU). First of all, these four poetic lines form a chiasm (ABB’A’) with the two central lines being the focus and the two external lines (1st and 4th) parallel each other. Lines 1 and 4 speak of where Ishmael shall dwell. Wild donkeys didn’t just survive, they prospered in wildernesses, deserts, and mountains (Job 24:5; 39:5–8). Ishmael possessed the survival skills of a wild donkey. So he and his descendants resided in the great expense of wilderness, desert, and mountains east of Canaan (specifically, east of the residences of Isaac in the Negev near Beer-lahai-roi; Genesis 24:62; 25:11; cp. 16:14), Gerar (Genesis 26:6), and Beersheba (Genesis 26:23). That region includes the Arabah south of the Dead Sea and the mountainous region of Seir southeast of the Dead Sea (see map in Post #7 under Edom, Edomites). The Ishmaelites inhabited the region between Havilah east of Egypt and extending toward Assyria including cities or villages like Dumah, Tema, and Kedemah (Genesis 25:12–18).

That’s but half of the story, since sixty years later, Isaac and Rebekah produced twins: Jacob and Esau (Genesis 25:19–26) who would divide the family over their sibling rivalry. Since Esau’s father Isaac was Ishmael’s half-brother, Ishmael was Esau’s uncle. Due to Esau’s alienation from Isaac and Jacob, he chose to marry his cousin Mahalath, daughter of Ishmael and sister of Nebaioth (Genesis 28:9). Thus the descendants of Nebaioth (the Nabataeans) descended from Ishmael, but were cousins to the descendants of the Edomites whose ancestral head was Esau. Esau, like his uncle Ishmael, was an expert outdoorsman and hunter (Genesis 25:27), perfectly suited for living in the wilderness, deserts, and mountains — places without fertile soil and abundant dew (Genesis 27:39). Such environments required the development of water systems conserving what little water would fall as rain (only 3–6 inches annually). The Edomites and Nabataeans excelled at such water conservation (see Post #7 under Sela).

In 1812 Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, disguised as an Arab merchant, discovered the ancient city of Petra, which he had heard about from Bedouins. The rose red ancient city of Petra sits about 50 miles south of the Dead Sea in Jordan. It occupied a key location along the ancient route by which camel caravans carried spices, perfumes, frankincense, myrrh, and silks throughout the eastern Mediterranean world. The queen of Sheba followed the same spice route to bring her valuable collection of gifts to Solomon (1 Kings 10:1–2; cp. Psalm 72:8–11). According to Scripture, nobles will bring such gifts to Messiah (Isaiah 60:1–7; cp. Matthew 2:1–12).

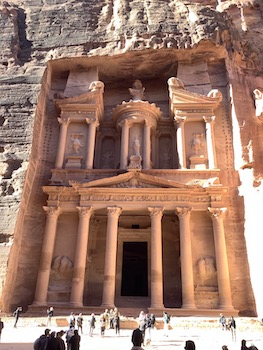

The Apostle Paul’s reference to Aretas of Damascus (2 Corinthians 11:32) indicates a king of the Nabataean dynasty of that name. The dynasty centered its power in Petra. A 2nd century BC Nabataean Aramaic inscription on the Petra-Gaza road in the Negev mentions “Aretas, King of the Nabataeans.” Aretas IV (9 BC–AD 41) nurtured the formation of Nabataean material culture with its distinctive art, architecture, pottery, and peculiar Aramaic script. During his long reign many of Petra’s rock-hewn monuments were constructed (e.g., the Theater and Qaṣr al-Bint). Some have proposed that Al-Khazneh (The Treasury) was his tomb. In many respects, Aretas IV’s cultural achievements parallel those of his contemporary, Herod the Great, whose mother was of Edomite (Idumean) descent. Herod Antipas may have married one of Aretas’ daughters (Shaʿudat?), though he later divorced her and married Herodias. John the Baptist condemned Antipas’ marriage to Herodias and Aretas sought to avenge his daughter’s divorce. Mark 3:8 includes people from Idumea who joined the crowds to hear Jesus’ teaching. It is possible some of those from Idumea actually were inhabitants of Petra. In addition, it is possible that Paul’s Arabian sojourn (Galatians 1:17) might have included a visit to Petra.

Obverse: Jugate busts of Aretas laureate and Queen Shaqilath (facing right) ḥeth and shin flanking.

Reverse: Two cornucopiae, crossed; between them, Aramaic/Nabataean legend: “Aretas, Shaqilath” in three lines. (Photo: Jared Clark)

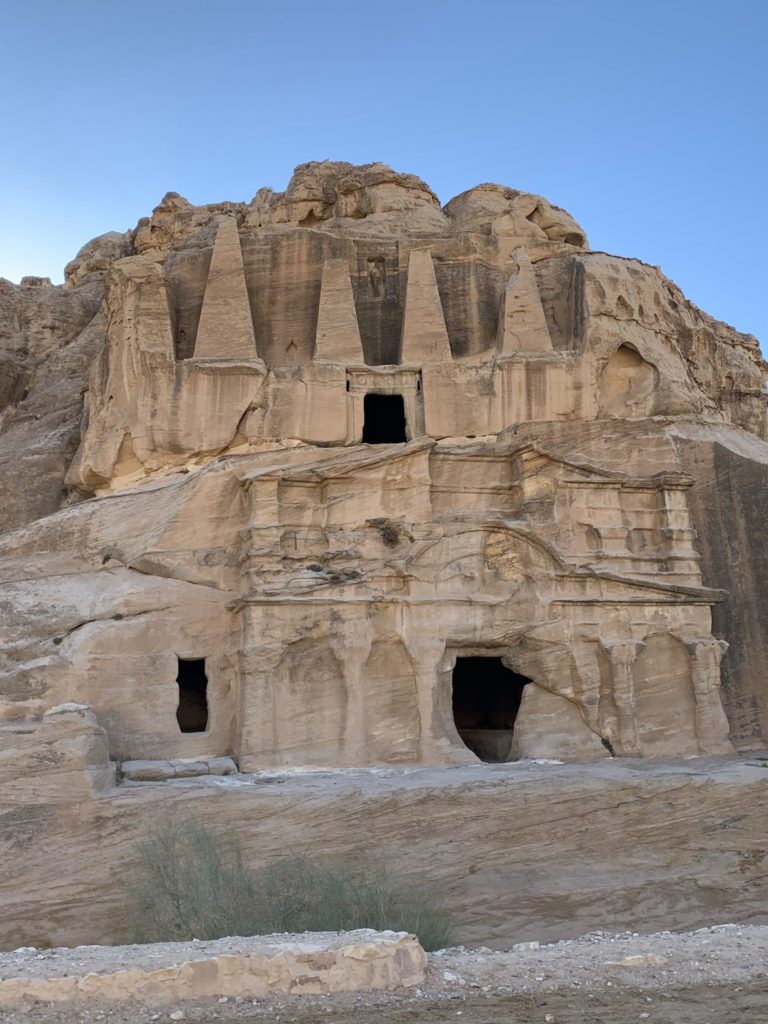

The area contains over 800 rock-hewn tombs. Petra’s tombs might remind Bible readers of Isaiah’s declaration concerning Shebna, one of Hezekiah’s officials (Isaiah 22:16): “What right do you have here, / And whom do you have here, / That you have hewn a tomb for yourself here, / You who hew a tomb on the height, / You who carve a resting place for yourself in the rock?” (NASU).

Eusebius (Onomasticon 36:13; 142:7; 144:7) and some present day scholars (e.g., Michael Avi-Yonah) identify Petra with the biblical Edomite city of Sela (Judges 1:36; 2 Kings 14:7) — for which, however, there is little evidence (see Sela in Post #7). So, even though Scripture never speaks of Petra specifically, the biblical connections are fairly numerous and significant.

Approach to Petra

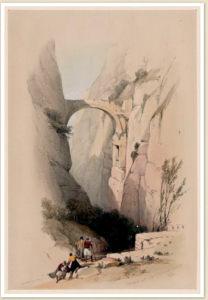

Reaching the city itself requires walking (or riding in a rented horse-drawn cart) through the Siq, a narrow ravine slicing through deep horizontal layers of sandstone. Most of Petra’s monuments have been carved out of the 975–1140-foot thick Umm Ishrin Sandstone Formation. Although many tourists focus on the abrupt and spectacular exit from the Siq revealing Al-Khazneh (The Treasury), the wonders commence as soon as one sets foot inside Petra National Park’s entrance and starts down the path leading to the Siq.

Although inhabitants have populated Petra from the Iron Age (1200–586 BC) to the 20th century, most scholars focus mainly on its role as the ancient capital of the Nabataeans during the Hellenistic period (332–63 BC). In fact, archaeologists and historians recognize a period of time known as the Nabataean Period (100 BC–AD 300). Crystal Bennett’s excavations proved Petra was inhabited in the Iron Age. Petra contains a Greco-Roman style theater (capable of seating an estimated 6,000–8,000 people), a Roman bath house (Nymphaeum), a huge temple (Great Temple), a colonnaded street, and many tombs. Excavations in 2002, directed by Philip C. Hammond (Arizona State University) and David J. Johnson (Brigham Young University) focused on the conservation of Petra and expanded past examinations of the architecture of the Temple of the Winged Lions.

Our guides conducted us into the park through the ticket kiosk and along the trail separated from the horse cart road by a rock median. Their interpretive explanations introduced us to the monuments, the Siq, the water system, the Treasury, and the Street of Facades. Arriving at the foot of the trail to the High Place of Sacrifice at 11:00 AM, the guides set us free to explore on our own. Along with a number of other members of our party, I started with the hike up to the High Place of Sacrifice. Then I descended to the Wadi Farasa and back into Petra Valley at Qasr al-Bint. After touring the colonnaded Cardo Maximus, Great Temple, Nymphaeum, and Theater, I purchased lunch and a drink at one of the Bedouin restaurants. Then I toured the Royal Tombs and wandered about a little more before heading back out the Siq, stopping at the recommended shop at Bab as-Siq.

In the 1st century BC the Nabataeans built a dam and diversion tunnel at the entrance to the Siq. The tunnel cuts through the rock for 290 feet to divert flash flood water through the Wadi Muthlim and the Wadi Mataha to the north around Jabal al-Khubtha. Then the water rejoins Wadi Musa in the Petra Valley.

Access to the interior of The Treasury has been curtailed after excavations in 2003 discovered eleven human burials in three different rock-hewn chambers below the main monument. Steps leading down into the chambers had been carved into the rock. Skeletal remains and Nabataean pottery confirm a date of the 1st century BC for the facade and tombs. Excavators found an altar in front of the northern burial chamber with possible frankincense residue (burned as incense) intact.

After picking out some gifts at the Bedouin shop, I walked out of the park and back to the hotel. Then I went back out to tour the Petra Museum — a beautiful facility packed with superb artifacts and a wealth of interpretive information on plaques and in digital presentations. Don’t skip the museum. Many of our party logged between 10 and 15 miles of walking (much of it ascending) on the day. The six major monuments I did not visit included the Monastery (Ad Deir), the Byzantine church, the Crusader fort, the Winged Lion Temple, the Palace Tomb, and the Lion Triclinium. In addition, I would love to take the trail to the summit of Rekem. These are on my list for any future visit.

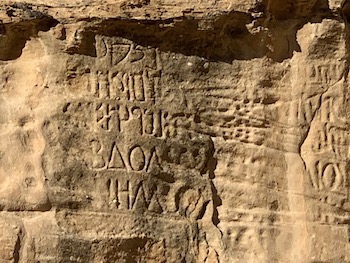

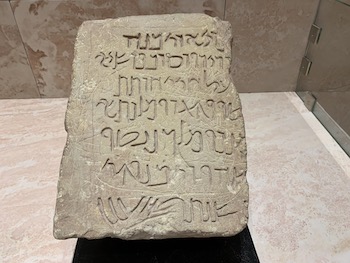

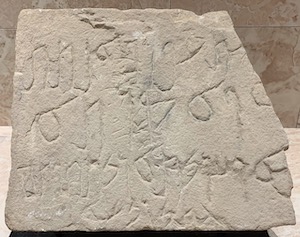

Nabataean Inscriptions

Nabataean (or, Edomite) writing occurs on a number of fragmentary inscriptions on both sides of the Arabah. The largest inscription consists of an ostracon from Tel el-Kheleifeh containing a list of names. Joseph Naveh (Hebrew University) first identified Nabataean/Edomite script as West Semitic influenced by contemporary Aramaic script. Just beyond the Djinn Blocks stands a sandstone cliff with a bilingual inscription. It relates to the Obelisk Tomb and Bab as-Siq Triclinium on the other side of the path.

The Nabataean text (the upper register) in Aramaic script announces:

ʿAbdmanku son of Akayus son of Shullay son of ʿUtayhu … built this burial-monument (for himself) and his descendants and their descendants for ever and ever (in the year…) of Maliku, during his lifetime.

Maliku refers to Malichos II (AD 40–70) during whose reign the tomb was prepared. The lower register provides an abbreviated version in Greek with the names Hellenized:

Abdomanchos son of (Ach)aios made this (funeral) monument for (himself) and for his (chi)ldren.

The az-Zantur inscription, written in Aramaic script, says, “These are the places which were made by son of Diodorus, the commander of the Cavalry for the safety of Aretas, king of Nabataea, and of Queen Hagru … Maliku and his children in the month of Shebat …”

Recommended Resources

Biblical Archaeology Review articles: Hershel Shanks, “The Petra Scrolls,”BAR 23, no. 1; Avraham Negev,“Understanding the Nabateans,”BAR 14, no. 6; Philip C. Hammond, “New Light on the Nabateans,”BAR 7, no. 2, and Judith W. Shanks, “A Plea for the Bedoul Bedouin of Petra,”BAR 7, no. 2.

Susan Orlean, “Zooming in on Petra,”Smithsonian Magazine (October 2018) provides a good overview of Petra and explanation of the use of drone photography and LIDAR for mapping.

Online Videos: The Smithsonian Channel produced the newest documentary on Petra in its Secrets Series, “Riddle of Petra” — if you have time for only one video documentary, choose this one. “Nova: Petra, Lost City of Stone” — 70 minutes; providing an updated reproduction demonstrating how the Nabateans carved these stone monuments and a scientific examination of Petra’s water system. “Petra, Jordan” — 20 minutes; spectacular views covering a wide sampling of Petra’s sites; no narration, some titles identifying locations. “In Search of History: The Hidden Glory of Petra” — 42 minutes; some interviews with archaeologists. “Civilizations, BBC Two: Petra, Jordan” — 4 minutes; purely introductory. “Who Carved These Incredible Structures in the Desert?” — 37 minutes; 2019 documentary.

Your thoughts on whether or not Obadiah refers to Petra ? We visited the Conovers who took a group of us down to Petra. Fantastic, but it was July and extremely hot. It has been interesting to see some of the footage from the Dakar Rally in Saudi Arabia and see the Nabatean tombs carved in the mountains there. Never realized their influence was so large!

Bob, Obadiah probably refers to all the major Edomite fortresses, not just one of them. Sela fits the picture just as well as Petra. The thing for us to remember about Petra is that the Nabataeans constructed (carved) the bulk of its spectacular physical structures during the intertestamental era. Also, the major fortress of Petra in the Iron Age was known as Rakmu or Rekem, which involves the large mesa on the northwestern edge of Petra Valley. There is very little difference between Rekem and Sela as far as Iron Age water systems and other structures. Both Sela and Petra fit Obadiah’s description beautifully — high rocky crags.