Capernaum

The city of Capernaum in Galilee gained its greatest attribute when Jesus chose it as the location of His residence after leaving His boyhood home in Nazareth. The name of the city is more accurately Kepher Nahum, “the village of Nahum.” Capernaum was the seat of customs for goods entering Galilee and then on into the rest of Israel. Everyone stopped in Capernaum. By moving to Capernaum, Jesus positioned Himself not only for spreading His message in Galilee, but even throughout the Mediterranean region.

Capernaum in the Bible

The New Testament refers to Capernaum by name in sixteen verses within the Gospels (Matthew 4:13; 8:5; 11:23; 17:24; Mark 1:21; 2:1; 9:33; Luke 4:23, 31; 7:1; 10:15; John 2:12; 4:46; 6:17, 24, 59) and one time as “His own city” (Matthew 9:1). Jesus performed more of the Gospels’ 35 recorded individual miracles at Capernaum than at any other site. Nine of those miracles were in Capernaum itself and one probably just offshore on the Sea of Galilee (stilling the stormy sea, Matthew 9:18, 23–27).

- Casting out the unclean spirit (Mark 1:21–28)

- Healing Peter’s mother-in-law (Mark 1:29–34)

- Healing the paralytic whose friends broke open the roof on a house to lower him down in front of Jesus (Mark 2:1–12)

- Healing the centurion’s servant (Luke 7:1–10)

- Raising Jairus’ daughter (Mark 5:21–24)

- Healing the woman who touched the hem of His robe (Mark 5:25–34)

- Healing two blind men (Matthew 9:27–31)

- Healing a dumb demoniac (Matthew 9:32–34)

- The stater coin in the fish’s mouth (Matthew 17:24–27)

Jesus made His home in Capernaum and began His public ministry in the synagogue (Matthew 4:13; Mark 1:21–29; Luke 4:31–37). Perhaps He chose Capernaum because two of His first converts lived here as fishermen (Peter and Andrew; Mark 1:29 — but, see John 1:44, which could indicate Bethsaida as another name for Capernaum). Jesus called his first disciples here (Matthew 4:18–22) and Peter also owned a house here (Matthew 8:14–17; Mark 1:29–34; Luke 4:38–39). Below is a photograph of what has been identified as Peter’s house, discovered beneath a Byzantine era octagonal church.[1]

The Romans established a small military post in Capernaum (Matthew 8:5–13 // Luke 7:1–10; John 4:46–53). The centurion stationed here sponsored the building of the synagogue (Luke 7:5). Capernaum also had a customs house (Matthew 9:9) for which Matthew served until Jesus called him to be His disciple.

After His first miracle at Cana, Jesus took His mother, His brothers, and His disciples to Capernaum for a few days (John 2:12). His second miracle involved the healing of a nobleman’s son ill in Capernaum (John 2:46–54).

Following a tour of Galilee, Jesus and His disciples returned to Capernaum where He questioned them about what they had been arguing with one another about as they traveled (Mark 9:30–37). Jesus and His disciples were on their way to Capernaum (the disciples by boat) when Jesus came to them walking on the water (John 6:16–21) — this miracle, if close enough to Capernaum, might be counted as the tenth at or near this location.

Jesus’ ministry around the Sea of Galilee connected with Capernaum (John 6:24–59) — it was in the synagogue there that Jesus said, “I am the bread of life” (John 6:48).

Jesus later condemned Capernaum, along with Chorazin and Bethsaida (Matthew 11:23; Luke 10:15). At Capernaum tax collectors from the Jerusalem Temple asked Peter if Jesus paid the temple tax. Jesus told Peter to go down to the Sea of Galilee, cast a fishing line and hook, and take the first fish — in its mouth Peter would find a coin to pay the tax (Matthew 17:24–26).

Archaeological and Historical Notes

Excavations at Capernaum have revealed houses built of basalt with small rooms surrounding an open courtyard. In the photo above, note the stairway at lower right. Such a stairway would lead to the roof. It was that kind of access that the men used to carry their paralyzed friend to the roof before they opened the roof and lowered him into the house in front of Jesus (Luke 5:17–26). Pertinent to this account, archaeological remains of homes in Capernaum reveal the following:

One major architectural difference between the buildings at Capernaum and those at contemporaneous sites (such as Chorazin and Meiron, as well as sites on the Golan and in Transjordan) is that the Capernaum builders did not roof their structures with basalt slabs (at least none were found in the remains). The Capernaum roofs were probably made of wood, covered with grass/straw and earth.

— John C. H. Laughlin, “Capernaum: From Jesus’ Time and After,” Biblical Archaeology Review 19, no. 5 (September/October 1993): 60

History of Capernaum

A jetty existed at Capernaum in the 1st century AD and fishing implements have been found among remains. Taken to Capernaum, Josephus received medical care for his battle wounds during the First Jewish Rebellion.

Three centuries after Jesus lived in Capernaum, Joseph, a convert to Christianity, probably built a church over what was thought to be Peter’s house (AD 330–337). Today a modern Roman Catholic church covers it. In the 4th or 5th century AD, a synagogue was built opposite the church. Today visitors see that synagogue’s remains (see discussion and pictures below). Synagogues normally were located in the center of a city, on a height, and facing Jerusalem. This 4th- to 5th-century synagogue (dated by coins found beneath the flooring) was built atop a 1st-century synagogue (basalt stones used for the earlier synagogue are visible on the south side of the synagogue’s outer wall).

The catastrophic earthquake of 749 AD brought Capernaum to an end although habitation by some people continued until the 11th century.

Archaeology of Capernaum

Captain Charles Wilson (British engineer and explorer) was the first to identify the ancient ruins of Tel-Hum with Capernaum in 1866. The Arab name Tal-Hum preserved the ending of Nahum (the Hebrew name of Capernaum, Kepher Nahum, means “the village of Nahum”). Not until 1894 did the ancient ruins at Capernaum gain the attention of archaeologists, even though Edward Robinson noted the ruins of a synagogue on the site in 1852. Robinson, however, did not identify the site with Capernaum, which he placed at Khirbet Minya about two miles to the southwest. The Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land acquired the western section of the site from the As-Samakiyeh Arabs in 1894. Eleven years later, in 1905, Heinrich Kohl and Carl Watzinger (Deutsche Orient Gesellschaft) began the first excavations. By means of probes they made in the synagogue ruins they were able to reconstruct the building’s plan. F. V. Hinterkeuser also commenced excavations in 1905 until 1914. From 1918 until 1921, Gaudentius Orfali carried on exploration at Capernaum. He had already excavated an ancient church under the present Church of All Nations at Gethsemane. He published some of his findings at Capernaum and initiated restoration of the synagogue before he died. He erroneously dated the synagogue ruins to the 1st century A.D. Virgilio Corbo and Stanislao Loffreda directed excavations through eighteen seasons (1968–1985). Their excavations rediscovered Simon Peter’s house and uncovered the foundations of the 1st-century synagogue beneath the ruins of the 4th-century synagogue (for an early report on this find, see Recommended Resources below, article by James F. Strange and Hershel Shanks).

The Greek Orthodox Church of Jerusalem acquired the northeastern section of the site a few years following the Franciscan acquisition of the western section. Up until 1930 the northeastern section failed to be excavated. The Greek patriarch of Jerusalem built a small church on that section in 1931. However, a few years later the church and a residence were abandoned. Located in a no-man’s land in 1948 between the Syrians and Israelis, the site faced more neglect. Following the Six-Day War in 1967, the Greek Orthodox Church regained control of the section archaeological work began in 1978 and continued through 1987 under the Israel Antiquities Authority and a consortium of schools from America and Canada (Averett College, Danville, VA; British Columbia University, Vancouver; Hardin-Simmons University, Abilene, TX; Notre Dame University, IN; Pepperdine University, Malibu, CA; Southwest Missouri State University, Springfield, MO.). Vassilios Tzaferis directed these excavations.

According to one report, the Franciscan archaeological work had to be stopped when a springtime level of the Sea of Galilee flooded the area of St. Peter’s house.[2] That provided evidence indicating that the Sea pf Galilee is higher today than it was in ancient times. From the available archaeological evidence it appears that a Jewish-Christian house-church, a synagogue, and a Roman bathhouse all existed simultaneously in 1st-century Capernaum. With excavations continuing at the site, someday a more complete picture of Capernaum at the time of Jesus might come to light.

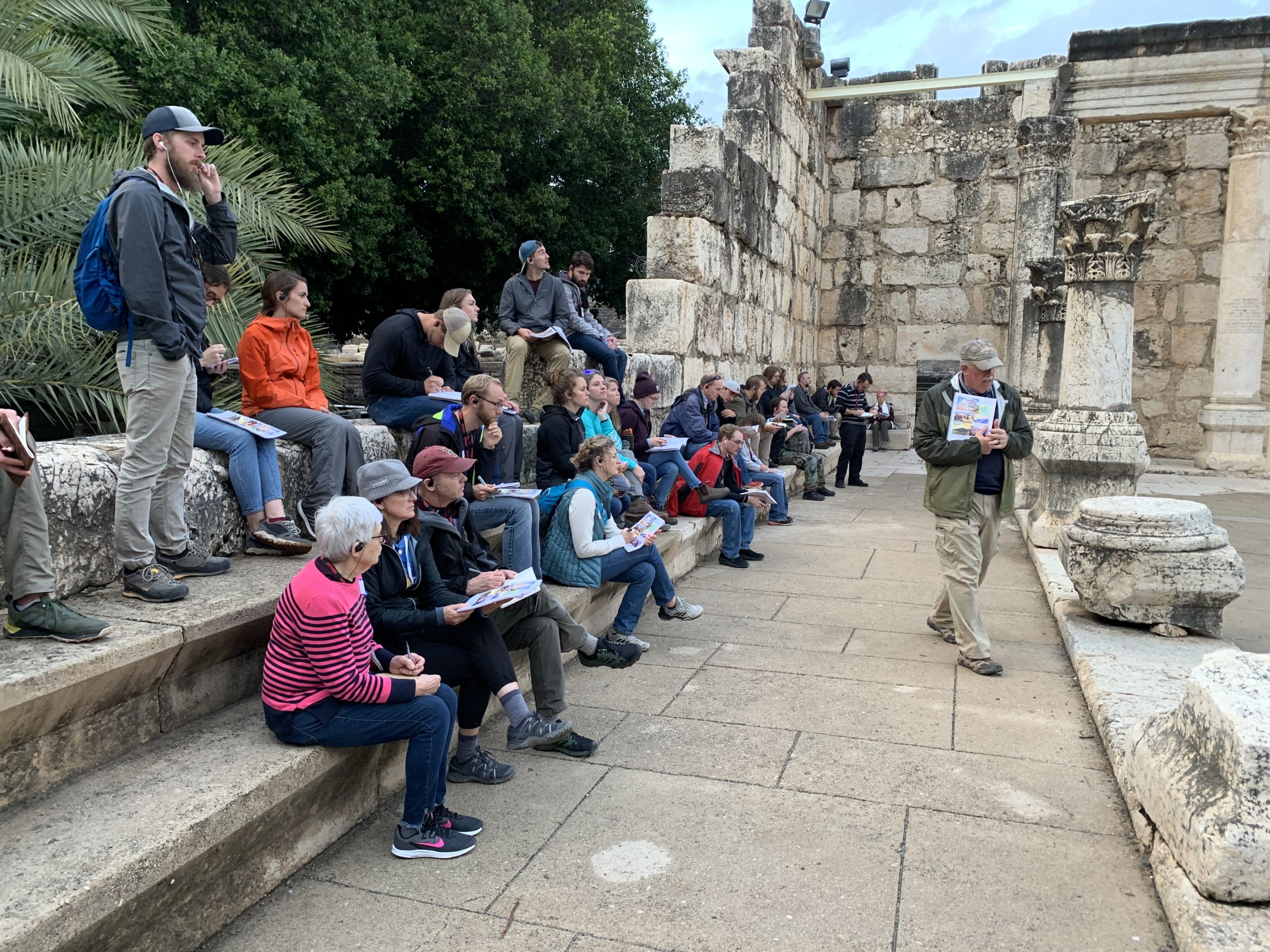

Ancient Synagogue

The ancient synagogue that visitors enter, sit in, and where they talk about Jesus’ life and ministry does not contain any first century artifacts. This structure dates from sometime after A.D. 350. However, outside the synagogue, if you look closely at the black basalt layer of stone below the current limestone ruins, you can observe what remains from the synagogue of Jesus’ day.

Of all the ancient synagogues partially restored in Galilee, this synagogue at Capernaum remains the largest. For example, the synagogue at Gamla is two-thirds the size of this one, the synagogues at Masada and the Herodium are each less than half the size of Capernaum’s. An attractive comparative photographic study of a number of the early synagogue ruins in Israel is contained in Todd Bolen’s Photo Companion to the Bible: Gospels (BiblePlaces.com, 2017); see, also, the article by Rachel Hachlili in Recommended Resources below.

Note in the photo above that the black basalt wall beneath the 4th-century synagogue’s white limestone wall sits at a slight angle — the limestone wall sits about nine inches off the lower wall at its southern end. This set of western walls for the two synagogues measures about 78 feet in length.

Roman Bathhouse

In the northeast section excavators discovered a 2nd-3rd century Roman bathhouse measuring 64 x 20 feet. They found clay hypocaust[3] tiles for raising the floor of the caladium (heated room). Three tiles were found still embedded in the floor of the caldarium (hot room), where they served as bases for the hypocaust pillars. In addition, they located the tepidarium (tepid room) and the frigidarium (the cool room). Another room’s function might have been as a swimming pool) or a dressing room. According to John Laughlin,

Beneath the bathhouse at Capernaum were earlier remains belonging to the first century A.D. (our stratum IX). Since we did not want to destroy the later building on top, the full plan of this earlier structure is still unknown. In general, however, the outline of the lower building is similar to the bathhouse above it. If this first-century building was also a bathhouse, then this may confirm the existence of the Roman centurion and garrison at Capernaum referred to in the Gospels.

— Laughlin, “Capernaum: From Jesus’ Time and After,” 57

Below the 1st-century A.D. remains at the bathhouse the excavation found an Early Bronze Age wall (3300–2200 B.C.). Similar finds have been elsewhere under Capernaum’s 1st-century ruins. In addition to those early finds, remains of a Late Bronze (1550–1150 B.C.) dwelling were found under the synagogue. Other dwellings as well as some ceramics have been encountered from the Middle Bronze Age (2200–1550 B.C.) and the Persian Period (538–332 B.C.).

Harbor

Mendel Nun discovered the harbor at Capernaum by looking for areas where rocks from its rocky shoreline had been removed. Here’s his description of the harbor:

Along the shore ran a 2,500-foot-long promenade, or paved avenue, supported by an 8-foot-wide seawall. …

To protect the shore from storms, a promenade must be at least 2 feet above the maximum sea level. A modern promenade at Tiberias, built in 1932 on the western shore, is about 2 feet higher (684 feet below sea level) than the sea’s maximum level (686 feet below sea level). The ancient Capernaum promenade is about 3 feet lower (687 feet below sea level). …

Vessels at Capernaum could load and unload cargo and passengers on several piers that extended about 100 feet from the promenade into the lake. Some of the piers are paired and curve toward each other, forming protected pools. Others are triangular in shape.

— Mendel Nun, “Ports of Galilee,” Biblical Archaeology Review 25, no. 4 (July/August 1999): 26–27 (See this article for a drawing by archaeological draftsman Leen Ritmeyer depicting Capernaum’s harbor. )

Miscellaneous Artifacts

Strolling around ancient Capernaum presents visitors with an opportunity to view many stone artifacts that reveal some of the opulence of Capernaum prior to its destruction. Roman and Jewish motifs in stone carvings, as well as commercial and household stone implements (e.g., millstones). Below are a few samples.

Among the household furnishings uncovered at Capernaum archaeologists recovered white limestone vases, black basalt mortars, a variety of basalt containers, and a lot of ceramic pottery. The pottery finds included lamps, plates, bowls, pans, amphorae, pots, and cups.

Recommended Resources

- “Capernaum: City of Jesus and Its Jewish Synagogue.” Archeological Sites No. 8. Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs website. 26 November 2003. [Accessed 28 Nov 2020]

- Chancey, Mark A. “Capernaum.” Bible Odyssey website. [Includes links to related articles, videos, maps, and photos. Accessed 28 Nov 2020]

- Corbo, Virgilio C. “Capernaum (Place).” In The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, ed. David Noel Freedman New York: Doubleday, 1992. 1:866–69.

- Hachlili, Rachel. “Synagogues: Before and After the Roman Destruction of the Temple.” Biblical Archaeology Review 41, no. 3 (May/June 2015): 30–38, 65.

- Laughlin, John C. H. “Capernaum: From Jesus’ Time and After.” Biblical Archaeology Review 19, no. 5 (September/October 1993): 54–61.

- Nun, Mendel. “Ports of Galilee.” Biblical Archaeology Review 25, no. 4 (July/August 1999): 18–23, 25–31, 64.

- Strange, James F., and Hershel Shanks. “Synagogue Where Jesus Preached Found at Capernaum.” BiblosFoundation.org website. PDF reproduction of article from Biblical Archaeology Review 9, no. 6 (November/December 1983): 24–31.

- “Ten Top Discoveries.” Biblical Archaeology Review 35, no. 4 (July/August, September/October 2009): 74, 76, 78, 80–82, 84, 86, 88–92, 94, 96.

- Voitenko, Sergio and Rhoda. “Capernaum, the town of Jesus.” Sergio and Rhoda in Israel, Season 2, Episode 5, September 30, 2018. Video [10:38]

Footnotes

[1] See “Ten Top Discoveries,” Biblical Archaeology Review 35, no. 4 (July/August, September/October 2009): 74, 76, 78, 80–82, 84, 86, 88–92, 94, 96 for a good explanation of the site’s discovery and evidence leading to the identification.

[2] Mendel Nun, “Ports of Galilee,” Biblical Archaeology Review 25, no. 4 (July/August 1999): 25–26.

[3] “Hypocaust” refers to the hollow space for heated air, steam, or water under a floor in an ancient Roman building. Such construction occurs commonly in Roman bathhouses.