Magdala

For myself personally, Magdala provided a new opportunity to visit a site I had not previously visited. I was enthralled with the archaeological finds at this location and enjoyed walking through the excavations. The site sits on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee about one mile north of Tiberias. As the supposed hometown of Mary Magdalene and the proven site of a synagogue existing in Jesus’ lifetime, the site stirs up interest among readers of the Bible and students of the life and ministry of Jesus Christ.

Magdala History

Magdala’s founding, according to archaeological evidence, appears to have taken place around 363–332 B.C. in the Hellenistic era of Israel’s history. “Magdala” refers to a “tower” (Hebrew מִגְדָּל, migdol, cp. Isaiah 5:2) and comprises a common element in Hebrew place names (e.g., Migdol-‘Eder, Genesis 35:21 and Migdal-gad, Joshua 15:37). Indeed, a stone tower at the site stands approximately 20 feet in height and has walls 7 feet thick. Archaeologists have tentatively classified it as a water tower and might be a later form of a much earlier tower. Passing by the tower there is a street 13 feet wide. The Talmud (b.Pesaḥ. 46b) refers to Magdala as Nûnnaya (“Tower of Fish”). Josephus (Jewish Wars, 2.21.8; 3.9.7–3.10.5) identifies the town with Taricheae (Greek for “salted [or “pickled”?] fish”).[1] Magdala-Taricheae became a significant fish export center during the Roman period. During the First Jewish Rebellion Josephus fortified Magdala-Taricheae (A.D. 66), but Vespasian conquered it just one year later. It was also the site of “the only sea battle between the Romans and the Jewish rebels. It was a disaster for the Jews” (Strange, “Magdala,” in ABD, 4:464). Magdala’s inhabitants fled to Tiberias after its fall to Vespasian’s troops. But they could not escape his determination to crush the rebellion. Vespasian ordered 12,000 of Magdala’s former residents to be slaughtered in Tiberias’ stadium, 6,000 to be exported to Corinth to build a canal for Nero, and 30,400 to be sold into slavery (Jewish Wars, 3.10.10). Magdala’s citizens had torn down some of the synagogue structure to use for making a fortification wall. They also covered the more important rooms and furnishings of the synagogue with debris to protect them. They left the city without the Romans needing to raze it or burn it. That accounts for the high degree of preservation for the artifacts and structures currently being recovered by archaeologists.

Sometime before A.D. 518, Theodosius visited Magdala, which he identified as the birthplace of Mary Magdalene. Although the site of the New Testament town never was rebuilt the way other towns (e.g., Tiberias), Christian pilgrims continued to visit the site and associate it with Mary Magdalene.

Magdala and the Bible

No direct mention of Magdala appears in the New Testament. However, some Greek manuscripts in Matthew 15:39 substitute τὰ ὅρια Μαγδαλα [or Μαγδαλαν] (ta horia Magdala [or, Magdala]), “the region of Magdala [or, Magdalan]” for τὰ ὅρια Μαγαδάν (ta horia Magadan), “the region of Magadan.” The earliest of those manuscripts dates from the fourth century, but most date from the eighth or ninth centuries. Mark 1:39 reports that Jesus spoke “in the synagogues of the whole of Galilee.” Matthew 4:23 repeats this report and adds that Jesus also healed many sick people who came3 to him at the time of such visits. Since a synagogue existed in Magdala during Jesus’ lifetime, He probably came to this synagogue. In addition to the synagogue, the discovery of port facilities at Magdala agrees with the fact that Matthew 15:39 speaks of Jesus arriving in that region by boat. These details make the site of great interest to us as His followers. And, of course, the association of Mary Magdalene (Matthew 27:56, 61; 28:1; Mark 15:40, 47; 16:1, 9; Luke 8:2; 24:10; John 19:25; 20:1, 18) with the town adds to its importance.

Magdala served as a center for processing and selling fish from the Sea of Galilee. Many of the fish were salted and dried or even pickled. Fish and bread formed the typical diet for those living in Galilee, especially the poor. Therefore, the two fish in the young lad’s lunch may have come from Magdala. Jesus miraculously multiplied the two fish to feed more than 5,000 people (Matthew 14:15–17). Although Matthew 14:17, Mark 6:41, and Luke 9:13 all read ἰχθύας/ἰχθύες (ichthuas/ichthues, “fish”), John 6:9 has ὀψάρια (opsaria, “preserved fish”). Interestingly, a Greek document from A.D. 57 associates opsarion with τᾰρῑχεία (taricheia — whence the name of Magdala-Taricheae).[2]

Magdala Archaeology

Excavations

The Franciscans of the Custody of the Holy Land directed surveys and excavations at Magdala (1971–1976, 2007, 2008). During the latter period of time, the Israel Antiquities Authority also worked at the site to preserve significant ruins and artifacts (2002–2015). More recently, Anahuac University of Mexico South (Universidad Anáhuac México Sur) has led a project at Magdala (2010 to the present).

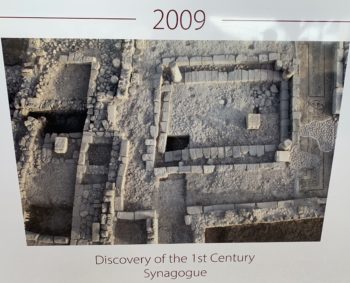

First-Century Synagogue

The most important find at Magdala is the synagogue dating from the first century A.D. In 2009 the Israel Antiquities Authority (under the direction of Dina Avshalom-Gorni and Arfan Najar) uncovered the synagogue. The evidence indicates its founding took place around A.D. 5–11. The rosette mosaic (photo below) dates from sometime after A.D. 43 — determined by a coin found under the tiles of the mosaic. The Magdala synagogue is one of only about seven first century A.D. synagogues discovered in Israel.

One of the first items to be uncovered by the archaeologists in 2009 consisted of the beautifully carved stone table in the photos at right and below. Its purpose remains a mystery, but few scholars question the idea that it depicts the temple in Jerusalem. On one end (photo below) the carving of a seven-branched menorah on a triangular stand is flanked by amphora. The top of the box has a rosette of 12 petals, perhaps representing the 12 tribes of Israel. Some scholars believe the top also bears a depiction of the table of shewbread. Another of the side panels appears to depict two wheels of the divine chariot (merkaba) with tongues of fire below each — providing a representation of the divine presence or throne.

If He visited the Magdala synagogue, Jesus did not see the rosette mosaic in the next photo, because it was not laid until sometime after A.D. 43, the date of a coin found under the mosaic.

Miqwaʾot / Ritual Baths

About 230 feet south of the synagogue a few upper class Jewish houses sit on both sides of a street. On one side of the wall bordering the street is a narrow alley (see photo below). Next to the alley are two miqweh apparently belonging to one house and entered from flagstone pavements inside the house. Each miqweh received (and still receives) groundwater directed by stone-encased openings.

Migdal is relatively close to the western shore of the Sea of Galilee, at the foot of the steep eastern slopes of nearby Mount Arbel. Consequently, the water in the three submerged miqwaʾot probably did not reach the site from the lake in the east, but instead, were sub-surface run-off waters of the last rains, coming from the adjacent mountain. These would create the uppermost layer of groundwater. When water is pumped out of one installation, the water recedes somewhat from the other two as well. This clearly shows that all three are fed by the same water table.

— Ronny Reich and Marcela Zapata Meza, “A Preliminary Report on the Miqwa’ot of Migdal,” Israel Exploration Journal 64, no. 1 (2014): 69.

Water System

Magdala’s main aqueduct began at Ain el-Mudawwara nearly three miles to the northwest. In addition, the structural evidence reveals ground-level channels from the Sea of Galilee (sometimes connected with the harbor) along with ground-water filled miqwa’ot (see above) and cisterns. The fresh water supply was abundant and enabled the town to grow rich on its fish processing capabilities.

Ports on the Sea of Galilee

Two different stone-built harbors have been discovered at Magdala — a small port and a a larger one. The larger has several perforated mooring stones (photo at left) where boats could be tied up. Archaeologists estimate that as many as 23 boats could have tied up at the larger port. One of the mosaics found at Magdala depicts a boat that would have sailed the Sea of Galilee (photo below).

Two different areas have been identified with regard to Magdala’s port: a promenade and a sheltered basin. “The promenade, which runs parallel to the shore, starts below the ruins of the Arab village of Migdal and continues to the north for about 300 feet. In the early 1970s, the outlines were clear and complete, but rapid silting and development have since altered the topography.”[4]

Something Else to See at Magdala

If you visit Magdala, don’t ignore the modern church, Duc in Altum (“Put out into the deep”; Luke 5:4 Latin Vulgate). Its architecture and the artistic contributions found within will reward the time you spend there. The pulpit surprised me with more than its size or even the view through the window behind it. Go down the stairs to the lower level for a chapel designed to reflect the synagogue and the stunning painting pictured below.

Recommended Resources

- Dell-Acqua, Antonio. “The Use of the Heart-Shaped Pillar in the Ancient Architecture: Examples and Circulation.” In SOMA 2012: Identity and Connectivity, Proceedings of the 16th Symposium on Mediterranean Archaeology, Florence, Italy, 1–3 March 2012, vol. 2, ed. by Luca Bombardieri et al. BAR International Series 2581/II. Oxford, England: Archaeopress, 2013. 1139–50.

- deSilva, David A. “Magdala: Mary’s Hometown.” Video; Bellingham, WA: Faithlife/Logos Bible Software Media, 2017. [Time: 8.25] A superb narrated media presentation providing a fairly complete tour of the archaeological finds at Magdala.

- “Explore Magdala.” Video; Appian Media, 2017. [Time: 10.47]

- Futers, Jeff. “Magdala: Head Archaeologist and Synagogue Expert.” Video, First Century Foundations, Season 8, Episode 12, 2018. [Time: 28.31]

- Israel Antiquities Authority. “Ancient harbors and anchorages.” (Accessed Nov 20, 2020)

- “Magdala: Home Town of Mary Magdalene.” Video; Voice of Faith Tours, 2020. [Time: 31.47]

- Nun, Mendel. “Ports of Galilee.” Biblical Archaeology Review 25, no. 4 (July/August 1999): 18–23, 25–31, 64.

- Reich, Ronny, and Marcela Zapata Meza. “A Preliminary Report on the Miqwa’ot of Migdal.” Israel Exploration Journal 64, no. 1 (2014): 63–71.

- Rudd, Steve. “Freestanding Columns: Antitype of Church and Christians” (accessed Nov 20, 2020).

- Strange, James F. “Magdala.” In The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, ed. David Noel Freedman. New York: Doubleday, 1992. 4:463–64.

- Zapata-Meza, Marcela, and Rosaura Sanz-Rincòn. “Excavating Mary Magdalene’s Hometown.” Biblical Archaeology Review 43, no. 3 (May/June 2017): 37–42.

Notes

[1] “τᾰρῑχεία, Ion. -ηΐη, ἡ, a preserving, pickling: in pl., αἱ Ταριχεῖαι factories for salting fish” H.G. Liddell, A Lexicon: Abridged from Liddell and Scott’s Greek-English Lexicon (Oak Harbor, WA: Logos Research Systems, Inc., 1996), 793.

[2] William Arndt, Frederick W. Danker, Walter Bauer, and F. Wilbur Gingrich, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 746.

[3] For discussion and pictures, including those at Magdala, see Steve Rudd, “Freestanding Columns: Antitype of Church and Christians” (accessed Nov 20, 2020). Also, see Antonio Dell-Acqua, “The Use of the Heart-Shaped Pillar in the Ancient Architecture: Examples and Circulation,” in SOMA 2012: Identity and Connectivity, Proceedings of the 16th Symposium on Mediterranean Archaeology, Florence, Italy, 1–3 March 2012, vol. 2, ed. by Luca Bombardieri et al., BAR International Series 2581/II (Oxford, England: Archaeopress, 2013), 1139–50.

[4] Mendel Nun, “Ports of Galilee,” Biblical Archaeology Review 25, no. 4 (July/August 1999): 29.