Hazor

Tell el-Qedah (Hazor) is one of the most thoroughly excavated sites in all Israel, joining Megiddo with a similar reputation. The site sits about ten miles north of the Sea of Galilee in a well-watered pass between the Sea of Galilee and the Huleh basin. It watches over an ancient crossroads of major branches of the Via Maris from the north (Sidon to Beth-shan) and the east (Damascus to Megiddo). The setting established Hazor as a leading city among its neighboring Canaanite kings (Joshua 11:1–5).

Biblical References

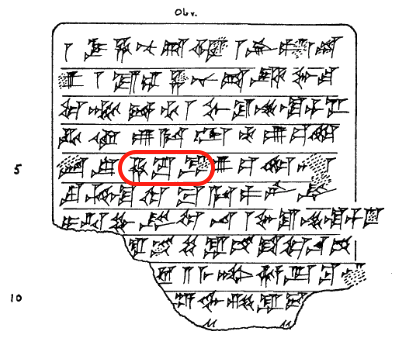

The name Jabin appears to have existed as a dynastic name for the kings of Hazor (Joshua 11:1, in the 15th century BC; Judges 4:2, in the 13th century BC). In 1992 excavators discovered a cuneiform tablet with the king’s name given as Jabin-Addu (“Ibni-Addu, king of Hazor”) in the 18th–17th centuries BC (in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem).

The northern campaign under Joshua targeted Hazor and destroyed it (Joshua 11:10–13). Thus Hazor is listed among the conquered cities (Joshua 12:19) and is subsequently allotted to the tribe of Naphtali (Joshua 19:32, 36). The seeming success of Joshua’s campaign, however, does not indicate a swift and total subjection of the Canaanites within the land Israel began to occupy. Exodus 23:29–30; Deuteronomy 7:22; and Joshua 11:18 provide testimony that Israel’s conquest of Canaan took time to accomplish and remnants of the Canaanites continued to test Israelite resolve.

During the time of the judges, Hazor emerges again as a threat to Israel when the city fields 900 iron chariots (Judges 4:13).[1] That results in Deborah and Barak meeting the Canaanite forces led by Sisera at Mount Tabor and, with God’s help, defeating them (Judges 4:14, 15, 23). Later, Samuel refers back to this battle during his final speech to Israel (1 Samuel 12:9).

During his reign, Solomon rebuilds the fortifications at Hazor along with Megiddo and Gezer (1 Kings 9:15). During Pekah’s reign in 733 BC Assyria’s Tiglath-pileser III leaves the city in ruins (2 Kings 15:29). One of the last historical references to Hazor occurs when Jonathan Maccabeus defeats Demetrius II (a Seleucid governor) on the plains near Hazor (1 Maccabees 11:67).

Historical Notes

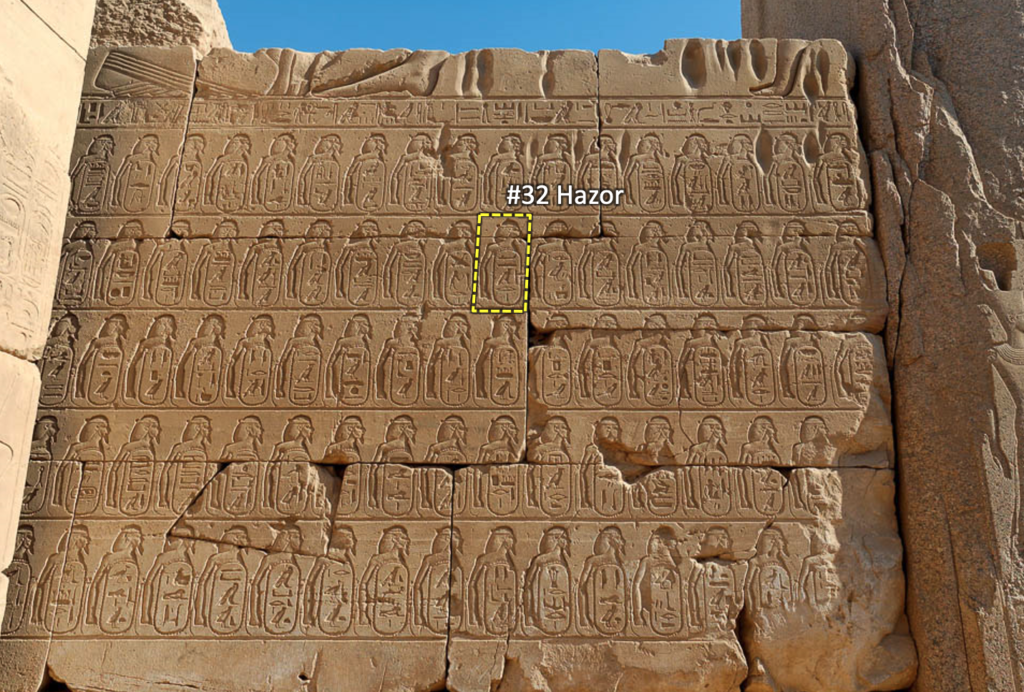

Tablets from Mari in Mesopotamia mention Hammurapi’s (1792–1750 BC) ambassadors who resided at Hazor. Following the Babylonian influence, the Egyptians exerted control over Hazor around the 15th century BC. The Egyptian execration texts (the Brussels Group, ca. 1800 BC) mention 64 places or peoples in Canaan. Hazor is included in the list, indicating that it was among the city-states emerging around that time in Canaan. Other pharaonic lists mentioning Hazor include those of Amenhotep III (1390–1352 BC), Set I (1294–1279 BC), and Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC). Three Amarna letters (1350–1330 BC) refer to the king of Hazor and one describes him as having authority over a number of cities — something somewhat unusual for that time.[2] Joshua 11:10 confirms Hazor’s significance and influence by referring to it as “the head of all those kingdoms.”

The first occupation of the site took place in the Early Bronze Age (ca. 2900–2300 BC). Successful Israelite occupation did not occur until about 950 BC (Solomon’s reign). The Neo-Assyrian annals list Hazor along with Abel Beth-Maacah and Dan as the prominent fortresses encountered by Assyrian troops moving through the region. After Tiglath-pileser III captured the city in 732 BC (2 Kings 15:29), Hazor never recovered.

Archaeological Notes

Hazor was a city of great size — perhaps as many as 30,000+ in the 18th–14th centuries BC. The site takes up about 200 acres — the largest tell in all Israel (ten times the size of the Old City of Jerusalem). The tell is so big that Israeli archaeologists had a hard time conceiving of a city 10–15 times greater than contemporary Canaanite cities. The main tell (mound) covers about 30 acres while the larger area comprising the lower city takes up 170–180 acres. (See picture above for the extent of the upper and lower cities.) Archaeologists have identified at least 22 different occupation levels (in which evidence has been found indicating 15 destructions) in the upper city. The lower city was occupied for about 500 years (18th–13th centuries BC).

John Garstang was the first to excavate Hazor (1928). Yigael Yadin directed the archaeological excavations on the site (1955–1959 with the J. A. Rothschild Expedition, and 1968–1972 with Hebrew University, Palestine Jewish Colonization Association, and Anglo-Israel Exploration Society). Amnon Ben-Tor began the Selz Foundation Hazor Excavations (in memory of Yigael Yadin) in 1990 and continues today (Hebrew University, Complutense University of Madrid, and Israel Exploration Society).

As mentioned above, the earliest occupation level at Hazor dates to the Early Bronze Age (ca. 2900–2300 BC). In Middle Bronze I (1900–1750 BC) the evidence of a city appears in some structures and tombs uncovered during excavations in the lower city. Then, in Middle Bronze II (1750–1650 BC) the city began to grow and prosper. Dever mentions the following discoveries from this period:

... domestic structures, accompanied by rock-cut cisterns (some with numerous scarabs), a system of underground tunnels (originally tombs?), and intramural jar burials, especially of infants. A large, but only partially cleared, mud brick palace or citadel ... A jar inscribed with a personal name is the earliest-known Akkadian inscription found in Israel ... multiple-entryway city gates, and ... city defenses ...

— William G. Dever, "Qedah, Tell el-," in The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, ed. David Noel Freedman (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 5:579

Around the large lower city archaeologists uncovered a large rampart (up to 50 feet high and 290 feet thick in some places along its two-mile long perimeter)[3] and moat as well as two city gates.

Among the structures of the lower city were a number of temples exhibiting a variety of styles, designs, and features. One of the temples of the lower city (Area H) included two finely worked orthostats (upright stones or slabs forming part of a structure or set in the ground) shaped like crouching lions flanking the entrance. Yadin uncovered one of them in the temple’s ruins. Ben-Tor found the other one on the acropolis where Israelites had later used in in constructing a different building.[4] These orthostats may have been remnants of a previous Canaanite king’s palace (Abdi-Tirshi, 14th century BC). Discoveries in the ruins of this temple include bronze figurines, a bronze plaque depicting a priest (with Syro-Mesopotamian parallels), and a liver model for divination.

On the acropolis were two temples in the area around the palace. As the first of a number of fiery destructions, the city of Hazor was burned in the mid-16th century BC. Then a second destruction by fire took place at the end of the 14th century BC — some scholars associate this destruction with Pharaoh Seti I (ca. 1294–1279 BC).

The acropolis (upper city) contains the chief administrative and religious facilities, as well as controlling access to the all-important water system so necessary to sustain the city, especially during a siege. The palace dates from the Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 BC) and was constructed with mudbrick walls atop a massive stone foundation (see picture below). Cedar of Lebanon was used for the floor and to provide planks placed in the mudbrick walls for support. Within the ruins of the palace, archaeologists discovered a large amount of decorative ivories similar to those found only a little more abundantly at Megiddo.

One of the ash layers from Hazor’s destructions measures around 3 feet deep (cf. Joshua 11:11, 13; Judges 4:1–3, 23–24). Evidence for the fiery destruction can be seen in the two photos above. But, when did this destruction take place? That is the debate in which archaeologists have divided into several camps with their opinions. With several burn layers, archaeologists have a lot of evidence to identify and to interpret in sorting out the sequence of the layers and their individual dates and events. According to Kaiser and Wegner, “The case for a 1400 BC destruction of Jericho is just as strong as the 1400 BC date for the destruction of Hazor, despite the subsequent ravages of weather and the debate over chronological issues at Jericho.”[5] Schlegel describes two Israelite destructions supported by the biblical text with the burn layer belonging to the earlier of the two:

Biblically, credit for the final destruction of Canaanite Hazor should go to the Israelites following the victory of Deborah and Barak (Judg. 4:24; Map 4–5). Earlier destruction-by-burning evidence at Hazor could be associated with Joshua. The Bible shows that during the 170 years separating Joshua and Barak, the Canaanites were able to resettle Hazor. That the Israelites in Joshua’s day took ‘all the spoil of these cities and the cattle’ (Josh. 11:14) suggests that they were not able to immediately or successfully inhabit many of the conquered cities (cf. Josh. 13:13; Map 4–2). In any event, it should be emphasized that the destruction of the Canaanite cities by the Israelites was the exception rather than the rule. Only Hazor was burned during the northern campaign, as Jericho and Ai were earlier. The Israelite policy was to preserve the physical structures of the city in hope of inhabiting them.”

—William Schlegel, Satellite Bible Atlas (N.p.: William Schlegel, 2013), 42

Among the palace ruins excavators also discovered a number of mutilated figurines, images, and statues (see the two photos above). Archaeologists have characteristically attributed such evidence to the zeal of the Israelites to eradicate the idolatry of Hazor’s Canaanite inhabitants.

After the site had lain in ruins for nearly 200 years, Israelite occupiers began reconstruction on the acropolis. Under King Solomon the reconstruction of an entirely new city took place. Typical of Solomonic fortified cities, Hazor had a casemate wall and a large gate with six chambers (cp. Megiddo and Gezer; 1 Kings 9:15).

This city also was destroyed, perhaps by Ben Hadad of Damascus (cf. 1 Kings 15:18–20; 2 Chronicles 16:4). After that, either Omri or Ahab rebuilt Hazor once again. Israel needed the fortress to help protect the nation from Assyrian invasion from the north. It seems likely that it was during this time that engineers with expert geological advice dug a 62-foot rectangular shaft through solid rock and then an 82-foot stepped tunnel to find the aquifer in the hill — the same technique as followed at Gezer. A 4-roomed building controlled its entrance. The following description gives a fairly good picture of what the water system entailed:

The system is situated just above the springs that issued from the foot of the mound and consists of a huge pier, a tunnel and the approach to the pier. The pier was cut through the early strata of occupation, down to bedrock. Its upper part was supported by huge retaining walls, while the lower part was excavated in the soft limestone. The pier measures 40 feet by 55 feet at its upper end and narrows to about 25 feet by 30 feet at the bottom. The tunnel, 15 feet high and 15 feet wide, slopes down in a series of steps over a distance of more than 90 feet. At the outer end of the tunnel is a small pool from which water was drawn. The vertical measurement of the whole system from top to bottom is about 140 feet. An intricate system of approaches, terminating in a monumental gate, leads from the city to the pier.

— Avraham Negev, ed., The Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land, rev. ed. (New York: Prentice Hall Press, 1990), 171

Archaeologists always hope to come upon an archive of texts on a site within ancient Canaan or within ancient Israel. No archive has been found at Hazor to date, but more cuneiform texts have come to light at Hazor than any other site in Israel. The Center for Online Judaic Studies mentions a total of eight cuneiform tablets found at Hazor. One of those texts is the Jabin-Addu letter shown above (under Biblical References). During the 2009 excavations two small pieces of an Old Babylonian law code tablet were discovered on the surface between Area M (the entry area ascending from the lower city into the upper city) and Area A (the acropolis). The fragments contain portions of up to seven laws related to treatment of slaves, similar to the Law Code of Hammurapi.

Given that the fragments of Hazor 18 were written on local clay and recovered on the acropolis of the city, we may hypothesize that the laws of Hazor come from a royal law collection that was promulgated in the name of the king of Hazor. It seems much less likely that our fragment is a school tablet where laws from Hazor or elsewhere were copied onto Hazor clay as part of the school curriculum for training cuneiform scribes. The tablet seems well formed, the signs on Hazor 18a–b are well written, and the sign selection seems faultless, with repeated examples of the same sign drawn almost identically. Moreover, the scribe carefully structured his tablet so that each of the laws seems to occupy the same amount of space, with ample space for each and every sign, even without the use of horizontal rulings to divide the tablet face into manageable units. These are the markings of an experienced scribe, rather than a novice. Thus, we believe that our fragments ultimately come from a genuine copy of a local royal Hazor law collection.

— Wayne Horowitz, Takayoshi Oshima, and Filip Vukosavovic, "Hazor 18: Fragments of a Cuneiform Law Collection from Hazor," Israel Exploration Journal 62 (2012): 174

Perhaps one of the most significant of the cuneiform finds has a history reading like some sort of mystery novel mixed with some political intrigue. In 1962 a honeymooning couple from America literally stumbled across a clay tablet in the dirt road at Hazor. Being told it was probably just some sort of clay seal, they took it home with them. Years later they found out that it was a legal document written in cuneiform and that it actually mentioned Hazor and its king! The tablet finally made it to Israel. The handwritten transcription and translation below were made by William Hallo.

Mar-Hanuta and Irpa-Addu and Sum-Hanuta, three(?) servants(?), brought a lawsuit against the woman Sumu-la-ilu, in the matter of the house and orchard in the city Hazor and the orchard in the city Giladima. They came before the king for litigation. The king [judged] the case of the woman Sumu-la-ilu. Henceforth, whoever [shall bring] a lawsuit shall pay 200 (shekels?) of silver. (Witnesses and data formula largely lost.)

— William W. Hallo and Hayim Tadmor, "A Lawsuit from Hazor," Israel Exploration Journal 27, no. 1 (1977): 4 [bold emphasis added]

Another find appeared during excavations of the gate leading from the lower city to the upper city. Below the ascent into the upper city sits a basalt pavement with an elevated podium containing four small depressions into which a chair/throne might be set (see photos below). This could indicate a bêma where a judge might sit to hear a citizen’s case (cp. Job 29:7; Joshua 20:4; 1 Samuel 4:18; 9:18; 2 Samuel 18:24; 19:8; 2 Chronicles 32:6; Jeremiah 38:7). Or, the platform might have served as a miniature “high place” (bamah) for an idol or images involved in a cult installation (2 Kings 23:8).

An earthquake wreaked havoc with Hazor in the 8th century BC. The occupants quickly rebuilt it, but it was soon destroyed by Tiglath-pileser III in 732 BC (2 Kings 15:29; 1 Chronicles 5:26). When the Assyrians destroyed Samaria in 722 BC, the Northern Kingdom’s economic and political center shifted to Dan, skipping over Hazor, which never recovered. Its ruins were manned by an isolated post of Assyrian soldiers late in the 8th century and into the 7th century BC. In much the same manner, in the 4th century BC the ruins were altered for a Persian outpost. In the Hellenistic period the fort went out of use and the tell was finally abandoned.

Recommended Resources

- Aharoni, Yohanan. “Hazor and the Battle of Deborah—Is Judges 4 Wrong?” Biblical Archaeology Review 1, no. 4 (December 1975): 3–4, 26.

- Bechar, Shlomit. “How to Find the Hazor Archives (I Think).” Biblical Archaeology Review 43, no. 2 (March/April 2017): 55–60, 70.

- Ben-Tor, Amnon. “Excavating Hazor, Part One: Solomon’s City Rises from the Ashes.” Biblical Archaeology Review 25, no. 2 (March/April 1999): 26–28, 30–33, 35–37, 60.

- Ben-Tor, Amnon. “Who Destroyed Canaanite Hazor?” Biblical Archaeology Review 39, no. 4 (July/August 2013): 28–36, 58–59.

- Ben-Tor, Amnon, and Maria Teresa Rubiato. “Excavating Hazor, Part Two: Did the Israelites Destroy the Canaanite City?” Biblical Archaeology Review 25, no. 3 (May/June 1999): 22, 24–29, 31–36, 38–39.

- Hadashot Arkheologiyot: Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Online e-journal of the Israel Antiquities Authority. [I present the following three entries as examples of the wealth of reports available on this site. The Search (just type “Hazor” in the “Site” designation) will reveal a list with links to 21 reports from 2004 until 2020.]

- Bechar, Shlomit, and Amnon Ben-Tor. “Tel Hazor — 2016.” Hadashot Arkheologiyot 129 (2017).

- Bechar, Shlomit, and Amnon Ben-Tor. “Tel Hazor — 2017.” Hadashot Arkheologiyot 130 (2018).

- Bechar, Shlomit, and Amnon Ben-Tor. “Tel Hazor — 2018.” Hadashot Arkheologiyot 132 (2020).

- Hallo, William W., and Hayim Tadmor. “A Lawsuit from Hazor.” Israel Exploration Journal 27, no. 1 (1977): 1–11.

- Horowitz, Wayne. “Two Late Bronze Age Tablets from Hazor.” Israel Exploration Journal 50, nos. 1/2 (2000): 16–28.

- Horowitz, Wayne, Takayoshi Oshima, and Filip Vukosavovic. “Hazor 18: Fragments of a Cuneiform Law Collection from Hazor.” Israel Exploration Journal 62 (2012): 158–76. This article includes photos, drawings, transcriptions, translations, and analysis of these cuneiform tablet fragments.

- Israel Museum. Online photo archive of objects from Hazor.

- Lanser, Scott, and Henry Smith. “Hazor’s Destruction in Joshua/Judges (Part One).” Digging for Truth, Episode 60. July 14, 2019. Associates for Biblical Research. Video. [26:00]

- Lanser, Scott, and Henry Smith. “Hazor’s Destruction in Joshua/Judges (Part Two).” Digging for Truth, Episode 61. July 21, 2019. Associates for Biblical Research. Video. [26:00]

- Rosenberg, Danny, and Jennie Ebeling. “Romancing the Stones: The Canaanite Artistic Tradition at Hazor.” Biblical Archaeology Review 44, no. 1 (January/February 2018): 46–51,70.

- Wiemers, Galyn. “Archaeologist Amnon Ben-Tor Explains Hazor on Site.” YouTube Video. July 10, 2012. [14:58]

- Yadin, Yigael. “Hazor and the Battle of Joshua—Is Joshua 11 Wrong?” Biblical Archaeology Review 2, no. 1 (March 1976): 3–4, 44.

- Yadin, Yigael. “Yigael Yadin on ‘Hazor, the Head of All Those Kingdoms’.” Biblical Archaeology Review 1, no. 1 (March 1975): 3–4, 15.

- Zuckerman, Sharon. “Where Is the Hazor Archive Buried?” Biblical Archaeology Review 32, no. 2 (March/April 2006): 28, 30–37.

Footnotes

[1] “The reference to iron chariots (Judg 4:3) not only emphasizes this strategic advantage but also helps to date the account, since iron did not come into common use in Canaan until around 1200. A date of 1240–1220 for this oppression is not out of keeping with the biblical data or extrabiblical information gleaned from archaeological research.” Eugene H. Merrill, Kingdom of Priests: A History of Old Testament Israel, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2008), 183.

[2] “Moreover, note that it is the ruler of Ḫaṣura who has taken 3 cities from me. From the time I heard and verified this, there has been waging of war against him. Truly, may the king, my lord, take cognizance, and may the king, my lord, give thought to his servant.” EA 364:17–28; William L. Moran, The Amarna Letters (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), 362.

[3] Joel F. Drinkard, Jr., “Cities and Urban Life,” in Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary, ed. by Chad Brand et al. (Nashville, TN: Holman, 2003), 3o2.

[4] Garth H. Gilmour, “Hazor,” in Dictionary of the Old Testament: Historical Books, ed. by Bill T. Arnold and H. G. M. Williamson (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2005), 362.

[5] Walter C. Kaiser and Paul D. Wegner, A History of Israel from the Bronze Age through the Jewish Wars, rev. ed. (Nashville, TN: B&H Academic, 2016), 177.

This is one place, I would like to visit if able to return to Israel. We did not visit this area. It looks to be a beautiful spot with alot of early history.

Indeed, Hazor is well worth visiting. Unfortunately, many of the commercial group tours do not include it in their itinerary — there’s so much to see in Galilee that they have to cut out something, unless it’s a longer tour or a site requested at the time of booking a tour.