Due to the amount of information I desire to communicate about Beth-shean, this site will require two posts: this post covers Old Testament Beth-Shean and Post #16 will cover New Testament Scythopolis.

Beth-shean / Beth-shan / Tell el-Husn

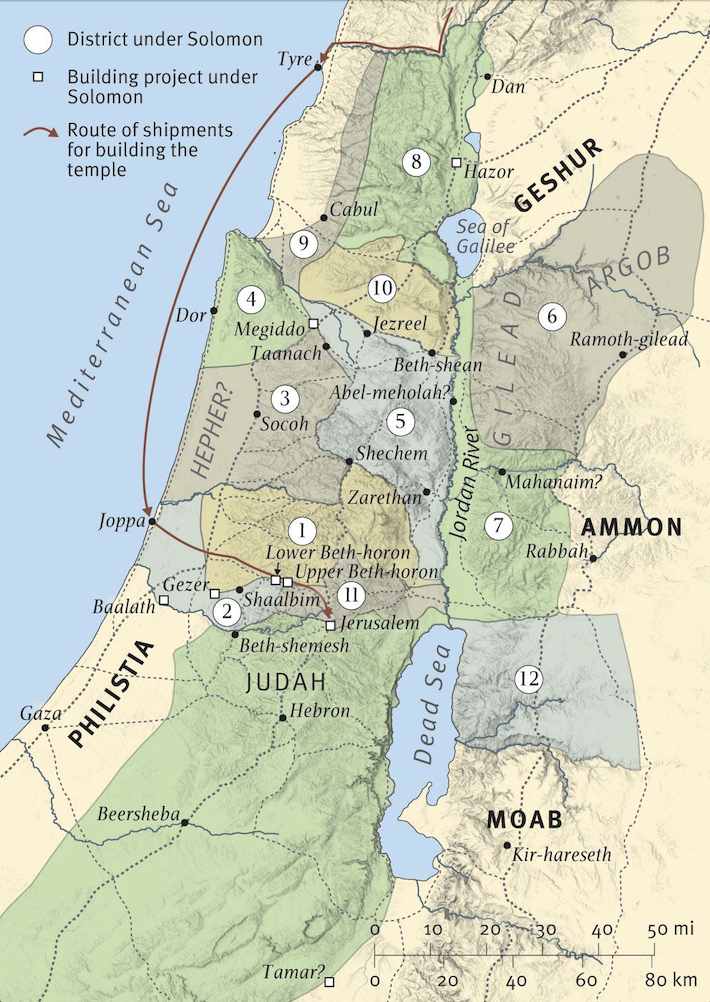

One of my favorite sites to visit in Israel is Beth-Shean (בֵּית שְׁאָן) — alternative spelling, Beth-Shan (בֵּית שַׁן), also known in New Testament times as Scythopolis. Its significance lies in the fact that it sits at the junction of the main east-west road from the Via Maris through the Jezreel Valley and the north-south road running along the Jordan River from Jericho. The tell is also known as Tell el-Husn. The tell rises to 350 feet below sea level, a surprise to visitors coming to it from the west, but no surprise to those coming to it from the Sea of Galilee (about 640 feet below sea level itself) to the north or from the south along the Jordan River. To give the location a bit of geographical perspective, look at a map and the photo below. Find the Jezreel Valley (running northwest and southeast) and note where it meets the well-watered Harod Valley (running farther southeast) and then where it empties into the Jordan Rift Valley. Mt. Gilboa sits southwest of Beth-shean on the south side of the Harod Valley. Across the Jordan River are the Transjordanian Hills of Gilead on the east side of the Jordan Valley.

George Adam Smith eloquently describes Beth-shean’s natural advantages:

The broad Vale of Jezreel comes gently down between Gilboa and the hills of Galilee. Three miles after it has opened round Gilboa to the south, but is still guarded by the northern hills, it suddenly drops over a bank some three hundred feet high into the valley of the Jordan. This bank, or lip, which runs north and south for nearly five miles, is cut by several streams falling eastward in narrow ravines, in which the black basalt lies bare, and the water breaks noisily over it. Near the edge of the lip, and between two of the ravines, rises a high, commanding mound that was once the citadel of Bethshan, the other quarters of which lay southward, divided by smaller streams. The position, which may be further fortified by scattering the abundant water till marshes are formed, is one of great strength and immense prospect. The eye sweeps from four to ten miles of plain all round, and follows the road westward to Jezreel, covers the thickets of Jordan where the fords lie, and ranges the edge of the eastern hills from Gadara to the Jabbok. It is almost the farthest-seeing, farthest-seen fortress in the land, and lies in the main passage between Eastern and Western Palestine. You perceive at a glance the meaning of its history. Bethshan ought to have been to Samaria what Jericho was to Judæa—a cover to the fords of the Jordan, and a key to the passes westward. But there is this difference: while Jericho lies well up to the Judæan hills, and has no strength apart from them, Bethshan is isolated, and strong and fertile enough to stand alone. Alone it has stood—less often an outpost of Western Palestine than a point of vantage against it.

— George Adam Smith, The Historical Geography of the Holy Land, 7th ed. (New York: A. C. Armstrong and Son, 1901), 357–58

Historical Background

Excavations at Tell el-Husn reveal the site had been occupied since the 5th millennium BC (by conventional dating methods). It existed as a large inhabited site in the Middle Bronze Age (2000–1550 BC, which includes the era of the biblical patriarchs). Egyptian influence is especially strong in the artifactual evidence from the Late Bronze Age (1550-1200 BC).

Beth-shean is mentioned in the Egyptian Execration Texts (as Bait-shar), Thutmose III’s (1479–1425 BC) topographical lists, the El Amarna letters (once, as Bit-sani, in Letter 289 to Akhenaten from Abdi-Hepa of Jerusalem reporting that the men of Gath maintain a garrison at Beth-shean), and the topographical lists of Seti I (1289–1278 BC). A stela found at Beth-shean dates from the 14th century BC — one of three locally made basalt royal Egyptian stelae). Three stelae date from Rameses II (1279–1212 BC). In addition, a life-size statue of Rameses III (1184–1153 BC) was recovered. As an Egyptian administrative center Beth-shean was second only to Gaza.

When the Israelites under Joshua entered Canaan, they were unable to conquer Beth-shean (Joshua 17:11; Judges 1:27). Somehow Beth-shean finally became a major Israelite city in Solomon’s fifth district (1 Kings 4:12), 965–928 BC but, soon after, Pharaoh Shishak (Sheshonq) conquered it in 918 BC. The city was destroyed at time of Tiglath-pileser III’s invasion, 732 BC.

Biblical Background

The Old Testament city sat on the highest tell in Israel. Thus it has been referred to as the “Acrocorinth” (upper city). Beth-shean’s name appears nine times in the Hebrew Bible, starting with the apportioning of the land of Canaan to the tribes of Israel under Joshua’s leadership. The Canaanite city’s chariot force prevented the tribe of Manasseh (Joshua 17:11, 16) from taking possession of it (Judges 1:27). Over three centuries later, Philistine chariot warriors took the city from the Canaanites in the 11th century BC. In 1004 BC the Philistines hung the bodies of Saul and Jonathan on Beth-shean’s walls (1 Samuel 31:8–13). Twin Late Bronze Age temples uncovered at Beth-shean might be “the house of Ashtoreth” (1 Samuel 31:10) and “the house of Dagon” (1 Chronicles 10:10) associated with the display of Saul’s and Jonathan’s weapons and bodies. See David’s lament: 2 Samuel 1:17–27. Mt Gilboa, the battleground between the Philistines and Israelites, stands nearby — on its heights the Philistines had defeated Israel’s army and Saul and Jonathan had died. The men of Jabesh-Gilead in Gad’s tribal territory (east of the Jordan Valley) rescued the bodies of Saul and Jonathan from the Philistines and took them to Jabesh-Gilead for an honorable burial following the cremation of their remains.

After the incidents of Judges 19–20, Jabesh-Gilead was the source for 400 wives for the surviving Benjamite men (Judges 20:1–12). Saul came from the tribe of Benjamin (1 Samuel 9:1–2) and early in his reign he had rescued the people of Jabesh-Gilead (1 Samuel 11:1–11).

The map above depicts the administrative divisions during Solomon’s reign. Beth-shean was included among those cities placed under the administration of Baana, son of Ahilud, at Megiddo (1 Kings 4:12).

Archaeological Notes

From 1921 through 1933 excavations at Tell el-Husn were conducted by the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania under the direction of Clarence S. Fisher (1921–1923), Alan Rowe (1925–1928), and Gerald M. FitzGerald (1930, 1931, and 1933). In 1983 Yigael Yadin and Shulamit Geva directed work on the tell. Amihai Mazar (Hebrew University) continued the work (1989–1996).

Level XVIII comprises the bottom-most layer of occupation on the mound comprising the upper city of Beth-shean. That layer provides occupational evidence from the Pottery Neolithic Period (5000–4300 BC). In Level XIII buildings appear in the tell in the Early Bronze Age II (starting ca. 2900 BC) as well as pottery tied to the 1st Dynasty of Egypt (ca. 2850 BC). This level is also distinguished by “long ribbon-like flint knives. Although the ‘Bronze Age’ was well along by this time, flint continued to be used at Beth-shan, as in other parts of Palestine, until the Iron Age.”[1]

The Middle Bronze Age (2200–1550 BC) city at Beth-shean might have been visited by Abraham on his way to Shechem, since it sat at such a significant crossroads.

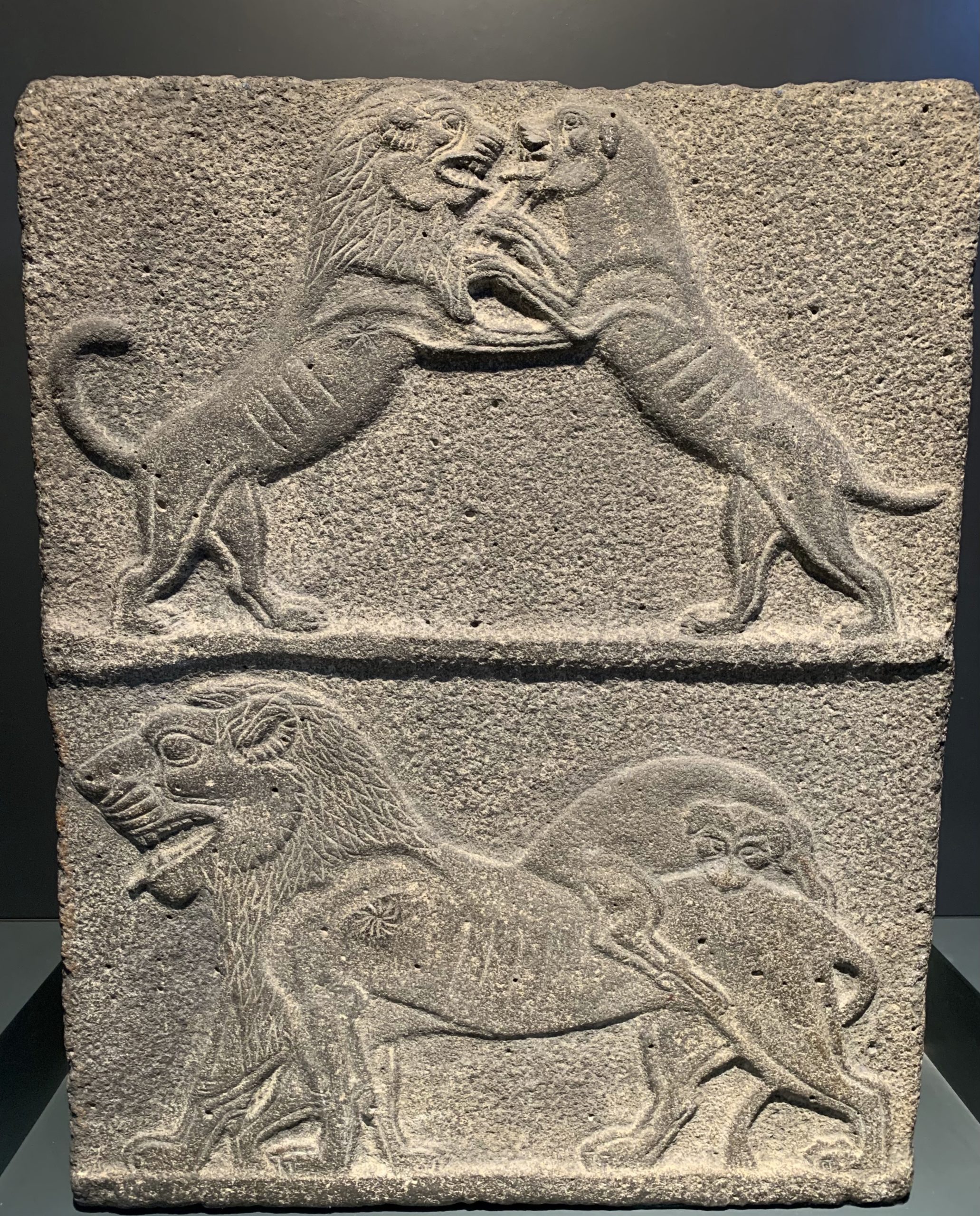

In the Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 BC) the Egyptians controlled Beth-shean. In Level IX archaeologists recovered a 14th century BC basalt relief of a lion and lioness at play (top) and a lion and dog fighting (bottom — see photo below). Excavators have also identified hieroglyphic inscriptions naming Thutmose III (1479–1425 BC) and Amenhotep III (1390–1352 BC), as well as a victory stela belonging to Seti I (1289–1278 BC). Foundation deposits reveal the names of Rameses I (1295–1294 BC) and Rameses II (1279–1212 BC), while a lintel displays the name of Rameses III (1184–1153 BC, a statue of this Pharaoh was also recovered).

A stunning variety of cult objects have been recovered from the excavations at Beth-shean. They include scarabs, figurines, reliefs, and vessels. The animals they depict include lions, dogs, gazelles, ibexes, goats, hippopotami, donkeys, bulls, pigs, elephants, and crocodiles. A variety of plant motifs (including vines and lotuses) as well as stars have been found.

Levels VIII and VII have been variously dated anywhere from as early as the 15th century BC or as late as the 13th century. These layers represent significant Egyptian occupation. A stele by Amenemopet, perhaps the architect of the palace, is dedicated to “Mekal, the god, the lord of Beth-shan.” In the North Cemetery archaeologists recovered anthropoid coffins combining both Philistine and Egyptian elements of style (see photo below).

Recommended Resources

- “Glorious Beth-Shean.” Biblical Archaeology Review 16, no. 4 (July/August 1990): 16–31.

- Mazar, Amihai. “Was King Saul Impaled on the Wall of Beth Shean?” Biblical Archaeology Review 38, no. 2 (March/April 2012): 34–41, 70–71.

- Mullins, Robert A., and Efraim Orni. “Bet(h) Shean, Israel.” Encyclopedia Judaica, 2008. Jewish Virtual Library.

- Sergio and Rhoda. “Beit-Shean and Scythopolis — The Ancient Roman City.” Season 2, Episode 1. September 2, 2018. YouTube video. [11.50]

- Thompson, Henry O. “Tell el-Husn — Biblical Beth-shan.” Biblical Archaeologist 30, no. 4 (December 1967): 109–35.

Footnotes

[1] Henry O. Thompson, “Tell el-Husn — Biblical Beth-shan,” Biblical Archaeologist 30, no. 4 (Dec. 1967): 114.