This final post reporting on my research trip to Jordan includes two sites we visited on our first day. I’ve done so in order to tie together some of the significance aspects of our visit to Gerasa and our later examination of sites in Israel.

Elijah’s Hill / Tell Elias

In order to identify sites related to biblical persons and events, we must give biblical evidence its proper primacy. The historical record in Scripture should be treated as historically accurate in light of its divine inspiration, the Holy Spirit’s superintendence of its writing, and its inerrancy. As we pursue lines of evidence outside Scripture, we need to give due consideration to the role of historical memory and commemoration. The biblical text identifies the location of Elijah’s ascent to heaven in a fiery chariot as being across the Jordan River opposite Jericho (2 Kings 2:1–14). The text describes Elijah and Elisha entering Moab on the east bank of the Jordan. The intertextuality of the account points back to the account of Moses’ departure from the mountain (Mt. Nebo) overlooking this current location (Deuteronomy 34:1–6).

Ruins of a 5th–6th century Byzantine church on this site reveal it was built upon layers of AD 1st century Jewish occupation and early Roman structures — including a well under the church’s floor. The memory of this significant and miraculous event in Israel’s history certainly would have been firmly established, perhaps even by a memorial or settlement on or near the site. It’s no surprise, therefore, that Christians would also memorialize the event, given the prophetic announcement of Malachi 4:5–6 and the expectation that continued even with the disciples of Jesus (Mark 9:11–13; Luke 1:17).

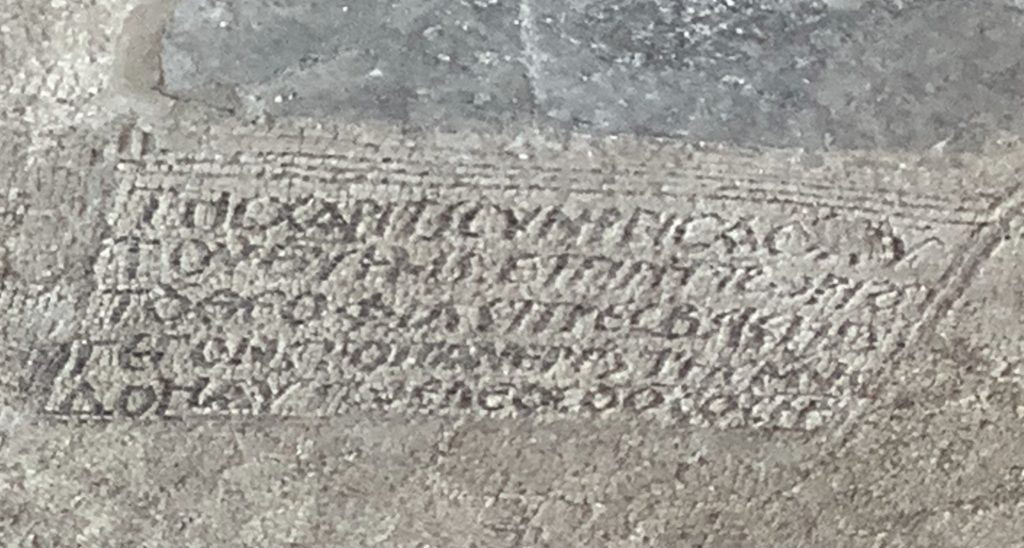

In the apse of the church a colored mosaic floor includes an inscription commemorating the founder of the monastery, Rhotorios. In the time following the conversion of the Roman Emperor Constantine, three sites were established in close proximity to one another: this monastery at Tell Elias, the cave of John the Baptist, and the church at Bethany Beyond the Jordan where Jesus was baptized. An informative web site with pictures and historical information provides a great visual summary — its map of the vicinity allows the visitor to see the overall setting more clearly.

Bethany Beyond the Jordan / Baptism Site

John 1:28 specifies that John was baptizing “in Bethany beyond the Jordan.” Although John also baptized at Aenon near Salim (John 3:23), it was at Bethany that he baptized Jesus (John 1:29–34). John places this particular Bethany “beyond the Jordan” — in other words, on the east bank of the Jordan River in Moab. The very fact that John the Baptist was identified with Elijah (Matthew 11:14; Luke 1:17; John 1:19–21) may be related to the proximity of the baptism site to Tell Elias (the Hill of Elijah).

Walking up to the Jordan River this far down its course to the Dead Sea, we were all struck by how small and muddy it was. It was the rainy season, which accounted for the muddiness. Farmers use its waters for agriculture in the Jordan Valley and both Israel and Jordan have dammed up some of the water sources of its tributaries. Therefore, the Jordan has shrunk in its flow and the Dead Sea has likewise decreased in its water level. The use of the water for agriculture has turned the Jordan Valley on both sides of the border (Jordan, Palestine, and Israel) into a fruitful plain growing olives, citrus, bananas, grapes, dates, barley, wheat, tomatoes, cucumbers, garlic, onions, and melons. The Jordan River flows more than 223 miles, but, because its course below the Sea of Galilee is meandering, the Dead Sea sits a mere 124 miles downstream from the Jordan’s source on Mt. Hermon.

“Beyond the Jordan” refers to the administrative region known as Perea (the name itself means “the land beyond”; Matthew 4:15, 25; 19:1; Mark 3:8; 10:1; John 1:28; 3:26; 10:40) in which Abel-shittim was located (see Post #1, Tell el-Hamman). Messengers from the official in Jerusalem went there to question John the Baptist (John 1:19–28) and the first disciples to follow Jesus started in this same area (John 1:35–51). Origen chose to insert “Bethabara” for “Bethany” in John 1:28 (Bethabara means “house of crossing,” perhaps a reference to the fords across the Jordan River). The textual critical issues continue to be thorny. The location we visited sits on the Wadi el-Charrar opposite Jericho. The 4th century AD Byzantine church whose ruins have been excavated at this site include a baptismal built on the east side of the Jordan River where the wadi empties into the river (see depiction above on the tourist plaque). No one can say for certain that the location of the Byzantine church was truly the place where John was baptizing or where he baptized Jesus, so the discussions and searches continue. Rainer Riesner, “Bethany Beyond the Jordan,” trans. Siegfried S. Schatzmann, in The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, David Noel Freedman, 1:703–5 (New York: Doubleday, 1992), provides one of the best summaries of the views and issues.

Gerasa / Jerash / Antioch

Our final day in Jordan included visits to Gerasa (modern Jerash, about 20 miles north of Amman) and Ramoth-Gilead. Gerasa was one of the cities of the Decapolis (see Matthew 4:25 and Mark 5:20), all located east of the Jordan River except Scythopolis. The title denotes ten cities. However,

Pliny (Nat. Hist. v, 74) enumerates Damascus, Philadelphia (Rabbath-Ammon), Raphana, Scythopolis (Beth-Shean), Gadara, Hippos (Sussita), Dium, Pella (Pehel), Gerasa and Canatha (Kanath) but admits that other writers give a different list. Ptolemy (Geography v, 14, 18) lists different cities, omitting Raphana but adding Abila, Lysianae and Capitolias. Stephan of Byzantium (Gerasa) mentions fourteen cities instead of the original ten.

— Avraham Negev, The Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land (New York: Prentice Hall Press, 1990), “Decapolis”

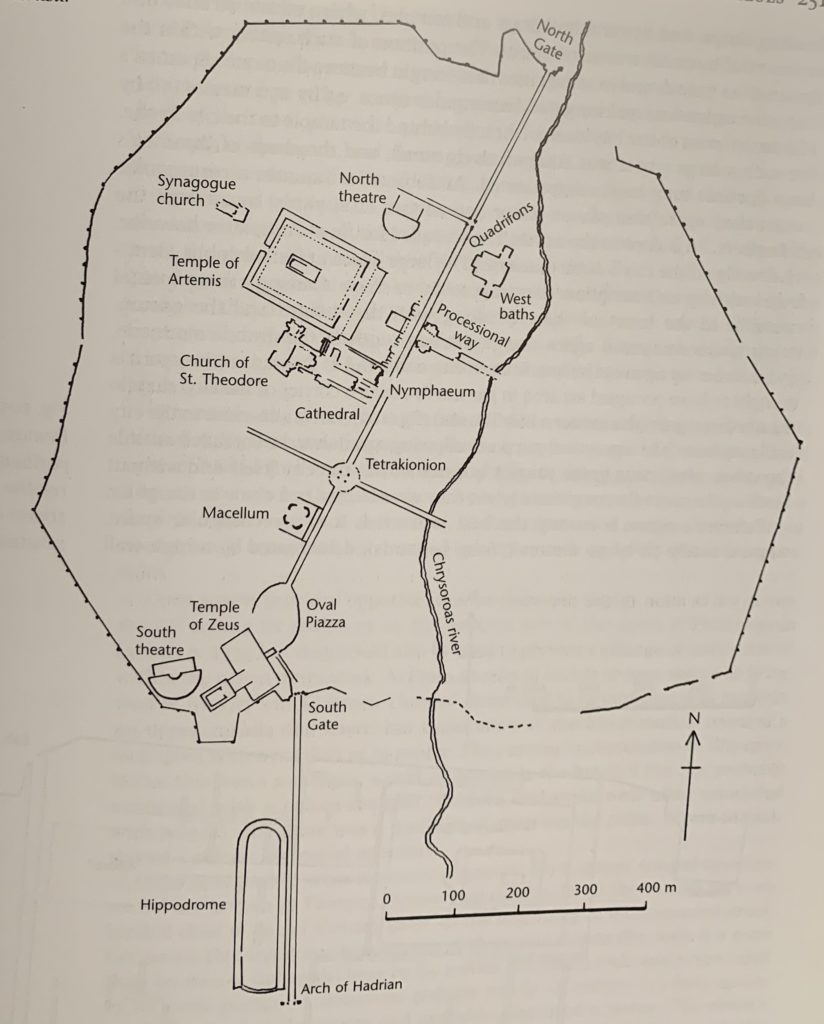

Gerasa sits on the King’s Highway with its Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine ruins covering over 200 acres. The city was the major center for travel between the cities of the Decapolis forming the connection to Adraha (Derʿa) to the north, Pella to the northwest, and Philadelphia to the south. Extensive excavations exposed one of the largest and most complete cities of its type. The Nabataean king Aretas III controlled the city when Pompey took the city from him in 63 BC. Pompey made Gerasa a member of the Decapolis. It was sometimes known as Antioch (or, Antioch on Chrysorrhoas — due to the river providing its water). During the First Jewish Revolt (AD 66–70) against the Romans, the Jews took control of Gerasa. Vespasian regained destroyed the city. By AD 75–76 a Hippodamian grid was adopted whereby streets met at right angles intersecting with the Cardo Maximus.

Gerasa presented us with evidence which would influence how we understand the Roman layout of Aelia Capitolina (Jerusalem) and its effect upon events in the life of Christ. The key individual in regard to the layout of both cities was the Emperor Hadrian (AD 117–138). Hadrian ordered the erection of triumphal arches in those cities of the Roman Empire where he had influence.

Hadrian typically honored Jupiter (Zeus) and built temples to him in many locations throughout the Roman Empire. He changed the name of this region to Syria Palestina, “which looks like a deliberate attempt to disassociate the name of the province from the Jewish people” — Kevin Butcher, Roman Syria and the Near East (London: British Museum Press, 2003), 46. Hadrian opposed Christianity as well as Judaism and sought to obliterate their holy sites by erecting Roman monuments over the top of them. Gerasa serves as the parade example of how Hadrian laid out the Roman cities he built — including the placement of temples in relationship to the Cardo Maximus. The Cardo Maximus is the major north-south road beginning at the oval piazza near the temple to Jupiter (Zeus) and running to the North Gate. Two temples dominate the city and sit at opposite ends of the Cardo Maximus. At Gerasa the temple to Artemis (Diana) serves as the second of the two.

The food market reminds the reader of Scripture of the issue Paul raised regarding eating meat offered to idols (1 Corinthians 10:25–33). The city required water as much as it did food, so a water system was constructed to meet that need. The city’s architects designed an elaborate spring house (Nymphaeum) for collecting and protecting the water and provide access to the populus. The overall water system included the means of getting the water to a reservoir. A wall or façade protected the reservoir and provided spouts and basins for filling containers.

The most elaborate structure of this type in the ancient Middle East was the Nymphaeum at Gerasa, constructed in the late 2d century A.D. The two-story Corinthian facade was a paradigm of Roman baroque architecture, combining rich architectural decoration with sculpture, jets of water, and a large pool. Similar monumental fountains were built during the Empire at Petra, Miletus, and Corinth.

— John Peter Oleson, “Water Works,” in The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, ed. David Noel Freedman (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 6:885

The temple at Gerasa to Artemis (Diana) brings to mind the biblical account involving her temple at Ephesus (Acts 19:21–41). For Gerasa’s possible relationship to a Gospel account regarding a demoniac, see “The Synoptic Gospels’ Inerrancy: Geographical Realities.”

Ramoth-Gilead / Tell er-Rumeith

Ramoth-Gilead is located in lower Gilead and tentatively identified with Tell er-Rumeith about 40 miles north of Amman (a little less than 20 miles northwest of Gerasa) not far from the Syrian border. According to Deuteronomy 4:43, Moses designated Ramoth-Gilead as a city of refuge for the tribe of Gad (cf. Joshua 20:1–9). Joshua designated it as a Levitical city for Merari (Joshua 21:38; 1 Chronicles 6:80). Under Solomon (971–931 BC), Ramoth-Gilead became an administrative district city with Ben-geber as governor over Gilead and Bashan (1 Kings 4:13). During the war with Ben-Hadad of the Arameans who had gained control of Ramoth-Gilead, Ahab (874–853 BC) attacked Ramoth-Gilead with the aid of Jehoshaphat king of Judah and died from wounds he suffered (1 Kings 22:1–40). Twelve years later, Ahab’s son, Joram, was also wounded in battle with the Arameans and their king Hazael (2 Kings 8:28–29). The prophet Elisha anointed Jehu as king over Israel (841–814 BC) at Ramoth-Gilead (2 Kings 9:1–13). Jehu then drove his chariot from there to Jezreel across the Jordan to the west to kill Joram (2 Kings 9:14–26). Thus the prophecies against the dynasty of Ahab were fulfilled (1 Kings 21:19–24; 2 Kings 9:7–10). The Tel Dan Stela attests to the historicity of these events in which Jehu participated.

The relationship of the biblical text to the archaeological evidence demonstrates again and again how the Bible’s records are historically accurate and reliable.

Tell er-Rumeith provides valuable information about a time and place poorly understood relative to the immediately surrounding regions (especially southern Syria). They reveal a small, yet well-fortified, site on the border of the kingdoms of Israel and Aram-Damascus, both at the peak of their power during the latter part of the tenth, ninth, and beginning of the eighth centuries BCE. The stratigraphy of Rumeith can also be correlated with military events in the region, as known especially from biblical texts.

— Tristan Barako, “Reconstructing Tell er-Rumeith,” The Ancient Near East Today 4, no. 4 (April 2016), ASOR website

Resources:

- Barako, Tristan. “Reconstructing Tell er-Rumeith,” The Ancient Near East Today 4, no. 4 (April 2016), ASOR website.

- Kennedy, Merrit. “Scientists Use Lasers To Map An Ancient City In Jordan.” NPR CapRadio, May 29, 2019. Enlightening article talking about LIDAR mapping of the ruins at Jerash.

- Lapp, Paul W. “The Importance of Dating,” Biblical Archaeology Review 3, no. 1 (March 1977): 13–17, 19–22. Lapp led excavations at Tell er-Rumeith until the spring of 1967. His article on archaeological dating, published posthumously, mentions Ramoth-Gilead. The topic of that article relates directly to our purpose for the research trip to Jordan.

Hi! This is my 1st comment here so I just wanted to give a quick shout out and tell

you I really enjoy reading through your blog posts.

Can you recommend any other blogs/websites/forums that cover

the same topics? Thanks a ton!

Thank you for the shout out. So far I have focused on resources in blogs and websites specific to each individual site I have been writing about. There are some, however, that provide information on a broad range of sites. Among those are the University of Melbourne’s Classics and Archaeology Virtual Museum, the BiblePlaces Blog by Todd Bolen, and the Biblical Archaeology Society’s Bible History Daily blog.