After one week of research on the ground in Jordan, we turned our attention to Israel for the next two weeks. On our first day, six of us drove a rented van south to the Negev and the Gulf of Aqaba. We went with two purposes in mind: (1) to visit the site of ancient Gerar and (2) to locate the Great Unconformity in the geologic column at Timna’. We accomplished both and also visited Tel Arad, the full-scale model of the Tabernacle at Timna’, and the Gulf of Aqaba. The daylong journey proved its worth several times over.

Gerar

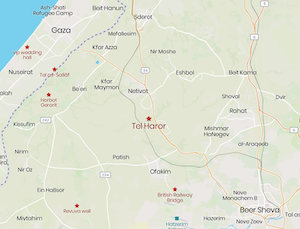

Archaeologists have identified ancient Gerar as one of four different tells located between Gaza and Beersheba: Tell Jemmeh, Tell Abu Hureira (= Tel Haror), Tell el-Shariah, or Tell et-Tuwail. The most likely site seems to be Tel Haror, about 12 miles southeast of Gaza and 12 miles northwest of Beersheba. It covers about 40 acres and sits on the north bank of Nahal Gerar. Since none of us had ever been to the proposed site for ancient Gerar, it took a little bit of map reading and driving along a dirt road until we came to what we believed to be the best option in the area.

As we walked around the tell, we became convinced we must have found the correct location. Excavations had obviously taken place over a fairly extensive area, including what could have been both lower and upper city sections. Eliezer D. Oren describes Tell Haror in The Anchor Bible Dictionary, ed. David Noel Freedman (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 2:989, as having 36 acres in the lower city and 4 acres of upper city in the northeast corner of the mound. The acropolis sits at about 425 feet above sea level and the lower city at 32 feet above sea level. I confirmed this with my cell phone GPS when I found a broken grinding stone on the edge of an excavated area on the acropolis and took the GPS reading and photo — I left the artifact where I found it.

Gerar’s connection to the patriarchs makes it a significant site. Genesis 10:19 gives Gerar as a geographical marker for the southern border of Canaan and indicates an association with Gaza. The same biblical text reveals a geographical alignment with Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah, and Zeboiim. The simplest and most likely understanding would indicate those cities should form the eastern anchor point of Canaan’s southern boundary.

Both Abraham (Genesis 20) and Isaac (Genesis 26) had lived for a time at Gerar. Abraham spent time there after living for awhile in the Negev between Kadesh and Shur (Genesis 20:1). His encounter with the king of Gerar, Abimelech, resulted in Abraham’s lie about Sarah being merely his “sister” (Genesis 20:2), because Abraham thought there was “no fear of God” in the city (Genesis 20:11). Later, during Isaac’s lifetime, a famine drove him to go to Gerar over which Abimelech king of the Philistines ruled (Genesis 26:1; see Note at end of this post). Isaac chose Gerar rather than to go to Egypt, because the Lord expressly prohibited Isaac from going to Egypt (Genesis 26:2). Isaac attempted to use the same lie his father had tried to use (Genesis 26:7). His lie was also discovered (Genesis 26:8–9). Isaac farmed the land at Gerar and gained a lot of wealth, prompting the envy of the Philistines (Genesis 26:12–14). The area around the tell is still being farmed today — its soil is still as fertile as the days of Isaac. Abraham had dug wells at Gerar during his sojourn there and Isaac discovered that the Philistines had filled them with dirt (Genesis 26:15). Isaac over away from the city and settled elsewhere in the same valley, but disputes over the wells he dug continued to create disharmony with the Philistines (Genesis 26:17–22). Eventually Isaac moved to Beersheba where he built an altar, dug a well, and reached a peaceful agreement with Abimelech of Gerar (Genesis 26:23–33).

When an Ethiopian army invaded Judah during the reign of Asa (911–870 BC), the Judean forces defeated them in battle at Mareshah and pursued them as far as Gerar (2 Chronicles 14:8–15), At that time Judah’s soldiers destroyed the cities around Gerar and looted them. That is the final mention of Gerar in Scripture. It does appear as a district marked on the Medeba map.

Oren directed excavations at Tell Haror for five seasons (1982–1988). He found that the city at this site possessed elaborate earthen ramparts and defense walls similar to those found at Tell el-Ajjul and Tell el-Fara. Tell Haror also had a temple complex dating back to the Middle Bronze. By Late Bronze the inhabited section had been confined mainly to the upper city. Philistine pottery and implements were recovered from the northwest corner of the lower city and dated to the 11th century BC. The acropolis areas destruction was dated to the 7th century BC. The site appears to have been occupied in the Persian period (5th–4th centuries BC).

Note regarding mention of Philistines in Genesis 26

Some biblical scholars identify the mention of the Philistines in this patriarchal account as an anachronism (e.g., John Skinner, Genesis, ICC, Scribner 1910, p. 364; E. A. Speiser, Genesis, ABC, Yale Univ. 1974, p. 159). The patriarchal narratives also mention the Philistines in Genesis 21:32, 34. Gleason L. Archer provided an excellent response to this supposed anachronism in his Encyclopedia of Bible Difficulties (Zondervan 1982), pp. 94–96. Nahum Sarna also offers a cogent argument against viewing these patriarchal references to the Philistines as anachronistic:

Unlike the depiction of the Philistines in Judges and Kings, these of the patriarchal period do not inhabit the Shephelah but are situated inland in the south. There is no pentapolis with seranim but a king of a single city who acts alone. The king has a Semitic name. Relationships between this people and the patriarchs are governed by formal treaties of friendship, whereas the later Philistines are inveterate enemies of Israel. Unless the Narrator had some particular reason for consciously falsifying history—and no such is forthcoming, especially since the ethnic identity of Abimelech and his subjects is of no significance for the understanding of the story—the references to the Philistines in the patriarchal narratives cannot be anachronisms. No later Israelite writer could possibly be so ignorant of the elementary facts of the history of his people as to perpetrate such a series of blunders, and to no purpose whatsoever.

Accordingly, the “Philistines” of patriarchal times may have belonged to a much earlier, minor wave of Aegean invaders who founded a small city-state in Gerar long before the large-scale invasions of the Levant, which led to the occupation of the Canaanite coast. The Narrator may be using a generic term for the sea peoples. At any rate, the Philistines of patriarchal times adopted Canaanite culture and lost their separate identity.

— Nahum M. Sarna, Genesis, The JPS Torah Commentary (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1989), 390

Moses could have used the name of the people occupying the area of Gaza and Gerar in his day as a way to describe an earlier people (Allen P. Ross, Genesis, Cornerstone Bible Commentary, Tyndale 2008, p. 138; R. A. S. Macalister, The Philistines: Their History and Civilization, Milford 1914, p. 39; Trude Dothan, The Philistines and Their Material Culture, Israel Exploration Society 1982, pp. 13–14). But that provides an unsatisfactory guess that assumes we now know all there is to know about the peoples inhabiting Canaan in the patriarchal period.

Rather than taking up the hermeneutics of doubt to explain away something we find difficult to understand, we should trust the historicity and accuracy of the biblical text and patiently await more evidence to confirm its accuracy. Bruce Waltke agrees with Archer and Sarna, rather than taking the anachronism view: “Probably these people should be identified as the descendants of the Caphtorites of 10:14. They differ from the Philistines of Judges in locale and government style” (Genesis, Zondervan 2001, p. 368). In other words, the group living in that region in patriarchal times were related to the Philistines as earlier colonists from Crete.

Kenneth A. Kitchen (On the Reliability of the Old Testament, Eerdmans 2003, p. 341) points out that Oren reported finding Cypriote pottery with Minoan characteristics at Tel Haror in strata centuries earlier than the Philistine pottery finds. he Aegean connection for the “Philistines” at Gerar fits archaeological evidence testifying to a very early (in the 3rd millennium BC) influence of Aegean culture in the eastern Mediterranean (see Edwin M. Yamauchi, Greece and Babylon: Early Contacts between the Aegean and the Near East, Baker 1967, pp. 26–32; see also, Edward E. Hindson, The Philistines and the Old Testament, Baker 1971, pp. 14–21).

Great post. Keep them coming please. It is so wonderful that the Bible again and again show it’s truthfulness on level of archaeology. Thsnk you for the update. God Bless your journey.

Thank you for your encouragement, Thomas. Post #2 will be up soon.