Tel Arad

Arad sits on the southern border of Old Testament Judah along the ancient caravan route to Edom. When Israel first came to Arad, the Canaanites together with the Amalekites withstood their assault and drove the Israelites as far as neighboring Hormah (Numbers 14:44–45; Deuteronomy 1:44). Later, when the Israelites returned to this Canaanite fortress in the final year or so of their wilderness journey, the king of Arad resisted them, but the Israelites destroyed the city and named it Hormah (Numbers 21:1–3), like its neighboring city. Then they continued along the route to Edom (Numbers 21:4). Joshua 12:14 lists both Arad and Hormah among the cities defeated in the conquest of Canaan by Israel.

After the conquest, some of Moses’ relatives (the Kenites) settled in the “Negev of Arad” (Judges 1:16). Shishak (Sheshonq), pharaoh of Egypt, conquered Arad in around 920 BC. His records mention both “Arad the Great” and “Arad of the House of Yrhm” (perhaps Yrhm refers to Jerahmeel, 1 Samuel 27:8–10; 30:26–31).

Yohanan Aharoni and Ruth Amiran both led archaeological excavations of Tel Arad (1962–1967). Amiran continued directing excavations until 1980. In 1976 Ze’ev Herzog conducted a season of excavation in the upper city (see “The Fortress Mound at Tel Arad: An Interim Report,” Tel Aviv 29, no. 1 [2002]). At that time Jack Campbell worked at reconstructing the fortress. Starting in 1977, the National Parks Authority commenced restoration and preservation work on the site under Herzog’s supervision. The lower city and its walls and towers enclose about 22 acres.

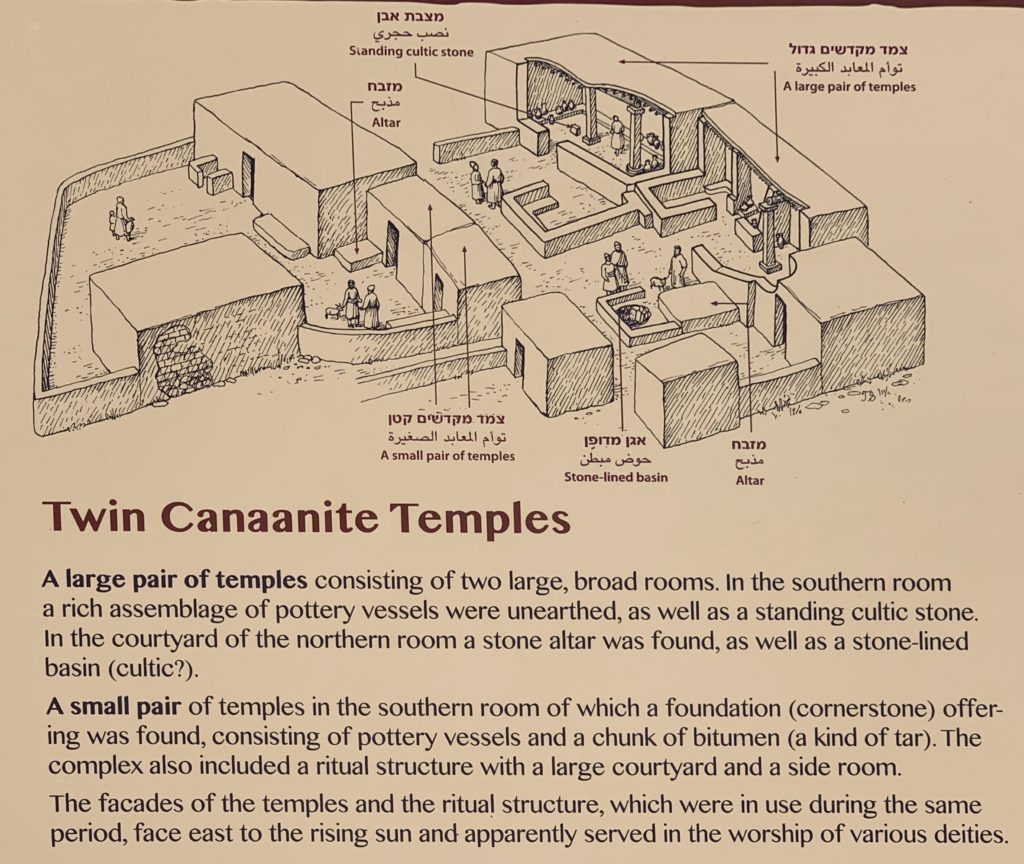

Even in the Early Bronze Age (2900–2700 BC) a large walled city sat on this location. Its wall was about 8 feet thick and eleven semicircular towers provided support and protection. Excavated structures include Canaanite twin temples (see figure below) sharing a common wall and opening into courtyards facing east.

Early Canaanites (3rd millennium BC) collected runoff water in the depression where this well (photo above) is located. When the Israelite occupation of the site got under way, they dug 68 feet through the rock to reach the upper aquifer. Laborers would descend from the fortress with jars and goatskins, draw water from the well, carry it about 400 feet to a channel cut in the rock, and dump the water into the channel through which it flowed into the two cisterns within the fortress. See Ruth Amiran, Rolf Goethert, and Ornit Ilan, “The Well at Arad,” Biblical Archaeology Review 13, no. 2 (March/April 1987): 40–44.

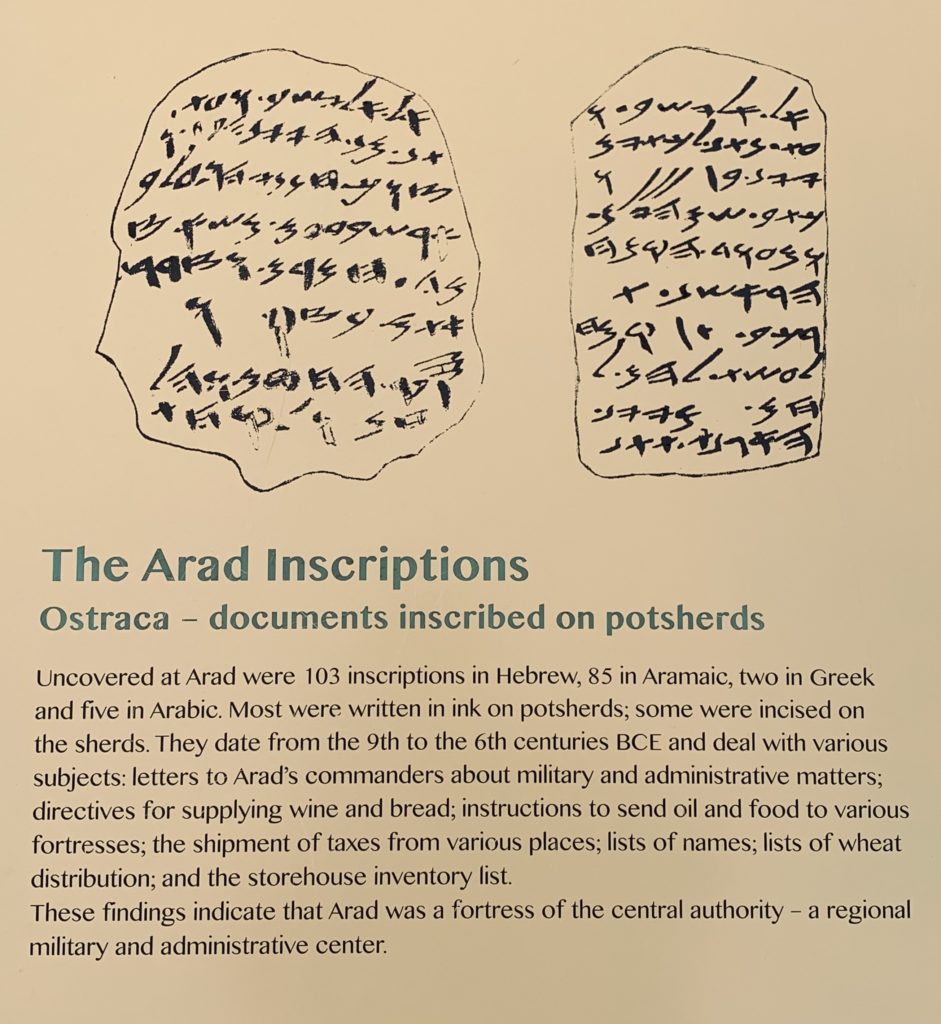

During the 11th and 10th centuries BC the upper city experienced renewed construction with a royal citadel enclosing a temple as well as official buildings for a royal, administrative, and military center. Destroyed by Pharaoh Shishak, the same citadel was rebuilt, destroyed, and rebuilt six times. A border fortress remained here until the collapse of the Nabataean kingdom in AD 106. The names Meremoth and Pashhur appear on two Hebrew ostraca found in the temple area. Both names occur in Nehemiah 10:3, 5. Pashhur is also the name of a priest who persecuted the prophet Jeremiah (Jeremiah 20:1–6). The existence of the biblical names in the ostraca does not mean they refer to the same persons as the Bible, but confirm contemporary usage of such names.

The two Arad ostraca depicted on the plaque above (displayed at Tel Arad) consist of #1 (right) and #3 (left). Here is what #1 says:

To Eliashib. And now give to the Kittim 3 bath of wine and write down the date [lit., name of the day]. From what remains of the first ground grain, have one homer of flour loaded up so they can make bread for themselves. It is wine from the mixing vessels that your are to give.

Ostraca #3 reads:

To Eliashib. And now give 3 bat of wine.for Hannanyahu gives you commands concerning Beersheba: you yourself load up and take there two donkey loads of dough. Calculate the wheat and count the bread. Take …

The name Eliashib occurs in Ezra 10:36. Robert B. Lawton, “Arad Ostraca,” in The Anchor Bible Dictionary, ed. David Noel Freedman et al., 1:337 (New York: Doubleday, 1992) rightly warns us to avoid basing historical statements on the Arad ostraca without sticking to what the inscriptions themselves actually say. See Anson F. Rainey, “The Saga of Eliashib,” Biblical Archaeology Review 13, no. 2 (March/April 1987): 36–39 for Rainey’s account of the discovery of these ostraca in the fortress of Arad.

The shrine at Tel Arad sits within the fortress on the acropolis. All kinds of disputes and hypotheses have swirled around its presence. Due to a reference to a person “staying in the house of Yahweh” in Arad ostracon #18, some scholars claim this shrine was dedicated to Yahweh. However, other scholars believe the reference is to the Temple in Jerusalem where someone from Arad might have been seeking refuge (cp. 1 Kings 1:50–51; Nehemiah 6:10). Comparing its presence with the contents of the Arad ostraca indicates the shrine was in use while Solomon’s Temple was standing. It includes a courtyard (with an altar for animal sacrifice), a main hall (holy place), and a holy of holies (reached by ascending three steps). A standing stone (massebah) sits in the back right corner (one of three found in the shrine). Two limestone incense altars sit at the top of the three steps. When archaeologists uncovered them, they still had burnt material (from incense) on their tops. It appears to date from the 10th century BC.

The fortress and the ostraca of Arad provide evidence for the strategic location of Arad and its relationship to the royal administrations at the times of both the United Monarchy and the Southern Kingdom. Arad provided protection for lines of communication, trade routes, and administrative/national borders. Visiting the site drives home the importance of Arad. The ostraca themselves testify to the accuracy of the biblical text, especially in regard to the events in the 6th century BC just prior to the collapse of the Southern Kingdom.

For a brief (5 minutes) video introduction to Tel Arad within its biblical contexts, watch TBN’s Watchman with Danny “the Digger” Herman. A video on YouTube (10 minutes) offers a good visual introduction to Tel Arad and its surroundings. The wind you hear seems constant — we encountered it during our own visit. Apart from a few inaccuracies (e.g., exaggerating the depth of the well, misidentifying the massebah as representing the tablets of the Ten Commandments, etc.) the video is worth taking the time to watch.