Megiddo

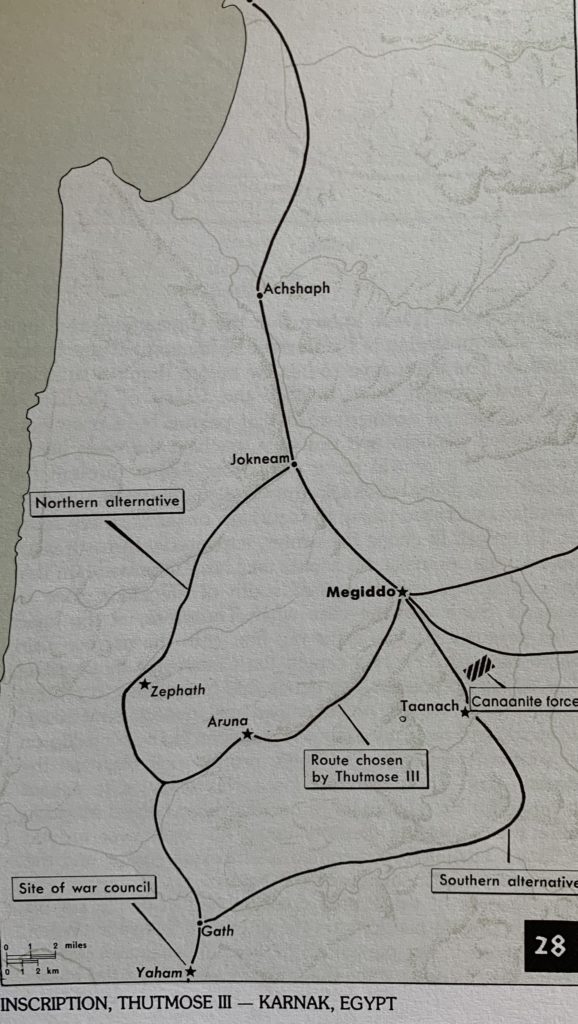

Introduction. Some scholars date the city of Megiddo from as early as 5000 BC. Of all the sites excavated in Israel, this represents the richest of all. The history of Biblical archaeology, together with the progressive development of a variety of methods and techniques finds expression in the archaeological excavations conducted at Megiddo. Its long history includes 25–30 destructions and reconstructions.. Pharaoh Thutmose III (1479–1425 BC) mentioned Megiddo in his annals. He defeated a Canaanite armed rebellion here in 1468 BC. An excellent account appears in Yohanan Aharoni et al., The Carta Bible Atlas, 4th ed. (Jerusalem: Carta, 2002), 31–32 (see map below). The Taanach tablets (image) and the El Amarna letters indicate that Megiddo served as a significant Egyptian garrison. Eight of the Amarna letters were sent from Megiddo (##242–48 and 365) These date from the reign of Amenhotep III (1391–1353 BC) or from that of Amenhotep IV (1353–1335 BC)..

(Jerusalem: Carta, 2002), 32 (Map 28). Note especially the three passes leading to Megiddo through the Carmel Ridge.

Biblical history. Megiddo’s significant location, abundant water supply, and proximity to Wadi Ara’s narrow passage on the main highway gave the city’s governing power control over the Via Maris (Way of the Sea), the trade route between Egypt and Asia. During the Israelites’ conquest of Canaan (ca. 1405 BC), they captured the city and its king (Joshua 12:21). Although Joshua allotted Megiddo to the tribe of Manasseh, the tribe failed to take Megiddo from its Canaanite population (Joshua 17:11–12; Judges 1:27). Deborah (ca. 1240 BC) mentions “the waters of Megiddo” in her song after she defeated Jabin, the king of Canaan (Judges 4:23–24; 5:19). When Israel finally succeeded in gaining control of Megiddo, Solomon (ca. 970 BC) assigned the city to his fifth administrative district under Baana the son of Ahilud (1 Kings 4:7–12). His strategic fortifications included the strengthening of the walls of Megiddo along with those of Jerusalem, Hazor, and Gezer (1 Kings 9:15).

Later, Shishak (924 BC), an Egyptian pharaoh, destroyed the city (1 Kings 14:25–28; 2 Chronicles 12). However, King Ahab of Israel rebuilt Megiddo. King Ahaziah (a.k.a. Azariah, 2 Chronicles 22:6, and Jehoahaz, 2 Chronicles 21:17; 25:23) of Judah (843–842 BC) died here at the hands of Jehu’s (842–814 BC) soldiers (2 Kings 9:27). A small seal belonging to Shema, servant of Jeroboam II (784–748 BC) or Jeroboam I (928–907 BC), was found at Megiddo by the German excavators (1903–1905; see below). In 733–32 BC Tiglath-Pileser III captured Megiddo and made it an Assyrian satrapy. Egyptian forces under Pharaoh Neco killed King Josiah of Judah (640–609 BC) in battle in the valley of Megiddo (2 Kings 23:29–30). The final mention of Megiddo in the Old Testament (Zechariah 12:11) refers to the mourning of King Josiah following his death.

Armies will gather for battle here in the future; Armageddon = the mountain of Megiddo (Revelation 16:12–16).

Archaeology. Archaeological remains at Tell el-Muteselim (with the auspicious meaning, “the tell of the governor”) make its identification as ancient Megiddo fairly certain. The German Oriental Society sent Gotlieb Schumacher there to conduct excavations (1903–1905). In 1908 Schumacher excavated a 60–75 foot wide trench through the entire north-south length of the 15-acre mound.

In 1925–1935 the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago began excavations, first under James H. Breasted, then later under Clarence S. Fisher, P. L. O. Guy, and Gordon Loud. Guy developed a system of aerial photography using a balloon. Unfortunately, these expeditions from the Oriental Institute omitted any correlation with the German finds, produced superficial reports, failed to accurately understand and identify occupational strata, and neglected many details. They uncovered the top four major strata in extensive digging. They succeeded in identifying 25 different levels of occupation extending back to the pre-Pottery Neolithic period (according to the standard system, approx. 8500–6000 BC) in a cave containing some bones and flint tools.. The first city wall appears to date to Early Bronze Age II (3000–2600 BC). The earliest city gate to be excavated is from the Middle Bronze IIA (2000–1800 BC). The palace discovered next to the Late Bronze Age I (1550–1400 BC) gate yielded a hoard of gold jewelry and carved ivories. A later palace from Later Bronze Age II (1400–1200 BC) likewise yielded treasures including 200 carved ivories.

Megiddo’s carved ivories (nearly 400 total), form the largest and most valuable assemblages in all the Near East. The styles include Canaanite (locally produced), Egyptian, Aegean, Assyrian, and Hittite. Evidently these represent a gathering of these decorative pieces over a period of perhaps two centuries of Megiddo’s history, but all from the Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 BC). The featured image for this post at the top of the page is a Canaanite furniture ivory of the 13th century BC from Megiddo (photo by Todd Bolen, “Photo Companion to the Bible: Judges,” BiblePlaces.com, 2020).

In the Solomonic era construction of a strong casemate wall and a large gate (allowing direct approach) strengthened the city’s fortifications — this particular find has, however, been questioned and is still being debated (see below). It appears that the sophisticated and extensive water system construction began in the time of Solomon (971–931 BC) and may have been completed in Ahab’s reign (873–852 BC). The vertical shaft descends 75 feet and a horizontal tunnel of 210 feet protected access to the water source.

Following Tiglath-pileser III’s conquest of Megiddo, the city was rebuilt with well laid out streets and large houses, with the stables converted to two large public buildings. At about the same time a large circular grain silo was constructed with two flights of steps for ingress and egress. It is 35 feet in diameter and 22 feet deep.

Yigael Yadin (Hebrew University) led archaeological excavation at Megiddo in 1960–1972. His discoveries involving superimposed structures, walls, and gates produced a new set of identifications correlating finds with the times of Solomon and of Omri. Abraham Eitan performed further analysis of Iron Age materials in 1974. A number of archaeologists have attempted to unravel the many strata at Megiddo. Proper identification faces the challenges of a variety of factors contributing to confusion: (1) tombs within the city consist of vertical shafts not easily identified with any particular occupation and probably being used over and over again by multiple periods, (2) continuous occupation of the site with reuse of previous materials for any reconstruction, (3) and no evidence of any massive destruction by fire.

Israel Finkelstein and David Ussishkin have directed the Megiddo Expedition for Tel Aviv University working together with Pennsylvania State University. The Megiddo Expedition started in 1992 and continues to the present..More recently, Mario Martin (Tel Aviv University) and Matthew Adams (W. F. Albright Institute of Archaeology) have directed excavation work at Megiddo (1998–2018).

Tombs. Schumacher discovered a spectacular tomb at Megiddo described as follows:

“Burial chamber I,” measuring ca. 2.6 by 2.15 m, was entered through a vertical shaft leading to a horizontal corridor. It contained a skeleton lying on a bench with a variety of adornments and scarabs mounted in gold. Four more skeletons, probably of his family or entourage, and many burial presents were found on the floor. The largest tomb was found empty and hence was not considered by Schumacher as a tomb (“chamber f”). This hypogeum is 5.6 m long, 3.7 m wide, and 3.1 m high and was entered through a shaft. It is beautifully built. … vaulted by fine-stone rudimentary corbeling—an early example of this building technique. … compared to the corbeled burial chambers from Ugarit.

— David Ussishkin, “Megiddo (Place),” in The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, 6 vols., ed. David Noel Freedman (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 4:670

In 2016 archaeologists discovered a previously unknown and undisturbed tomb of a prominent family dating to ca. 1700–1600 BC (the Late Middle Bronze Age). Its location lies near the Bronze Age palace uncovered in the 1930s. Dozens of ivory plaques in the tomb evidently once adorned a wooden box. Writing for National Geographic, Philippe Bohström describes the tomb as follows:

The chamber contained the undisturbed remains of three individuals—a child between the ages of eight and 10, a woman in her mid 30s and a man aged between 40-60—adorned with gold and silver jewelry including rings, brooches, bracelets, and pins. The male body was discovered wearing a gold necklace and had been crowned with a gold diadem, and all of the objects demonstrate a high level of skill and artistry.

— Philippe Bohström, “Exclusive: Royal Burial in Ancient Canaan May Shed New Light on Biblical City,” National Geographic News (online) March 18, 2018 (see link below in Recommended Resources)

Sacred area (in trench). The cult structures at Megiddo include a round stone altar measuring 12 feet by 36 feet and dating from about 2700 BC (Early Bronze). Uncut field stones were used in its construction. It includes a flight of seven steps to the top and an enclosure wall. Three temples of uniform plan sit nearby.

photo by Todd Bolen, “Pictorial Library of Bible Lands,” vol. 2 (BiblePlaces.com, 2012)

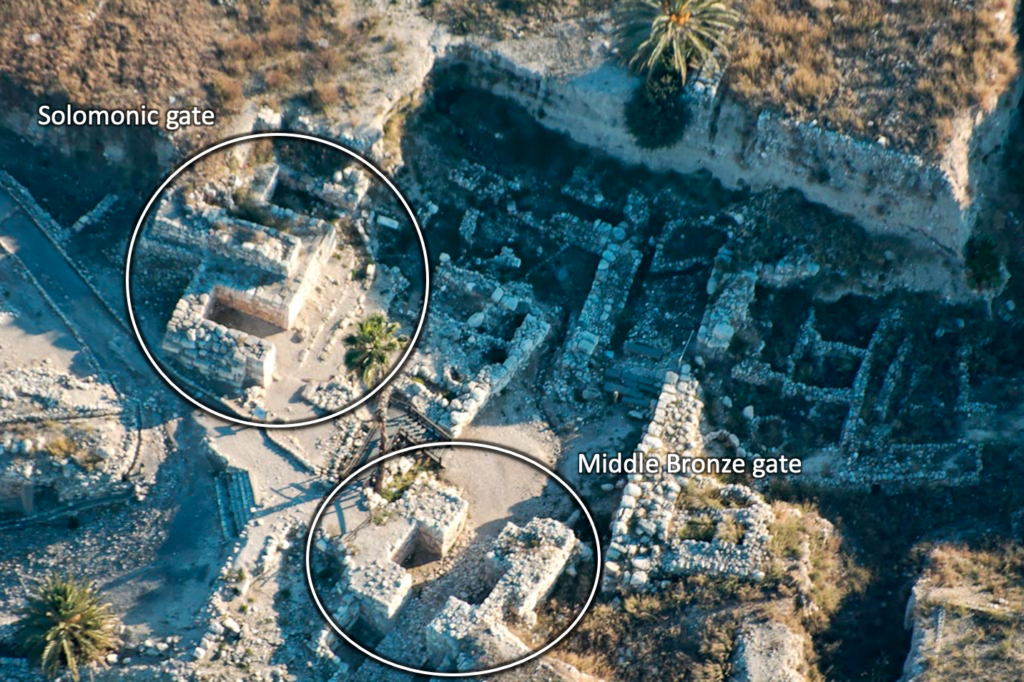

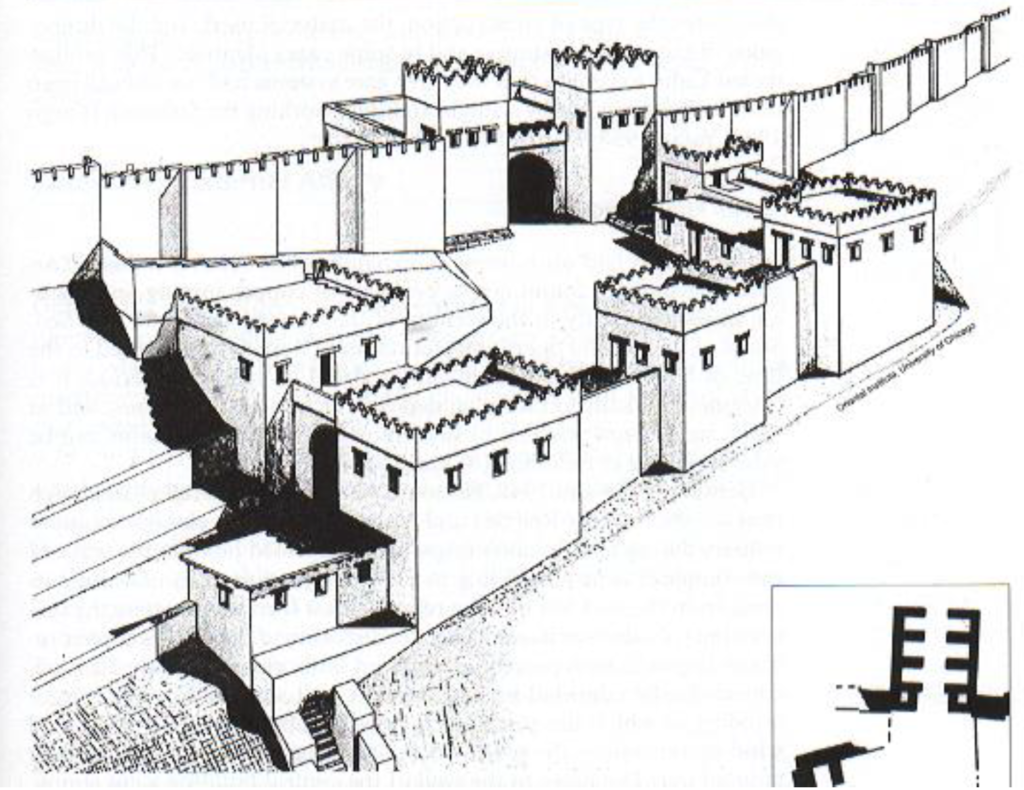

City gates. This particular element of Megiddo’s fortification still creates a large amount of debate. Archaeologists now believe what Yadin called the Solomonic gate is actually an earlier Canaanite gate. Another gate has been excavated above and offset from this gate — it may be the true Solomonic gate. The record in 1 Kings 9:15 confirms that Solomon did, indeed, fortify Megiddo and the gate here matches those found from the same period of time at Hazor and Gezer. Archaeologists are conducting a re-examination of all evidence and comparing it with recent finds at Hazor and Gezer.

photo by Todd Bolen, “Pictorial Library of Bible Lands,” vol. 2 (BiblePlaces.com, 2012)

Water system. The current form of the water system was recovered by excavation. Its construction began under Solomon (971–931 BC) and was probably completed under Ahab (873–852 BC). The system includes a vertical shaft 75 foot deep and a horizontal 210-foot tunnel. The Canaanites were probably the first inhabitants of the site to identify the water sources and provide some sort of water system.

Southern stable area. Or, could this have been a storage area? Some archaeologists date it to the time of Ahab, rather than to Solomon’s time. Guy (1931) first identified the structures as stables related to Solomon. Subsequent archaeologists (James Pritchard, Yohanan Aharoni, and Ze’ev Herzog) identified the structures as storehouses or military barracks. Later, Yadin and William Holladay returned to the idea the structures served as stables. As stables, the two structures could have housed up to 480 horses total for the city.

Large grain silo. This silo dates from the time of Omri (882–871 BC) and Ahab. It sits near the structures identified as stables, so might have contained feed for the horses. William Holladay calculated that this silo could have contained enough grain to feed over 300 horses for up to 150 days.

Seals. Three seals of quality make date back as far as the 9th century BC.

Schumacher … uncovered two seals near the gate to the Palace 1723 compound. The first is a jasper seal portraying a roaring lion and inscribed “(belonging) to Shema, servant of Jeroboam,” obviously Jeroboam II, king of Israel. The second, carved of lapis lazuli, portrays a griffin and is inscribed “(belonging) to Asaph.” The third seal, uncovered by Guy on the surface of the site …, is cut of serpentine. It depicts a griffin and a locust and is inscribed “Haman.”

— David Ussishkin, “Megiddo (Place),” in The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, 6 vols., ed. David Noel Freedman (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 4:677

Flood tablet. A shepherd from Kibbutz Megiddo discovered a broken cuneiform tablet in the excavation dump from the Oriental Institute excavations. Part of the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh is contained in the 37 lines of text on both sides of this clay tablet. Part of the epic includes an account of a great flood. The forms for the cuneiform signs date the tablet to the Late Bronze Age (1550–1150 BC). Some believe the find might indicate an archive at Megiddo, perhaps still buried and undiscovered. No such archive has ever been discovered in Israel. It’s a discovery many archaeologists dream of finding.

Recommended Resources

- Beck, John. “Ep. 8: The Holy Land / Megiddo: Built for War.” Video. Our Daily Bread Films, November11, 2019.

- Bohström, Philippe. “Exclusive: Royal Burial in Ancient Canaan May Shed New Light on Biblical City.” National Geographic News, March 18, 2018.

- Braun, Eliot. Early Megiddo on the East Slope (The “Megiddo Stages”): A Report on the Early Occupation of the East Slope of Megiddo. Oriental Institute Publications 139. Chicago: Oriental Institute, 2013.

- Cline, Eric H. “In Pharaoh’s Footsteps.” Archaeology Odyssey 1, no. 2 (1998): 32–34, 36–41.

- “I. The Debate Continues.” Biblical Archaeology Review 2, no. 3 (1976): 1, 12–18.

- Davies, Graham I. “King Solomon’s Stables—Still at Megiddo?” Biblical Archaeology Review 20, no. 1 (1994): 45–49.

- Finkelstein, Israel, and David Ussishkin. “Back to Megiddo.” Biblical Archaeology Review 20, no. 1 (1994): 26–33, 36–37, 39–43. Both of these men have directed the Megiddo Expedition (1994–present) for Tel Aviv University.

- Hansen, David G. “Megiddo, the Place of Battles.” Associates for Biblical Research, 5 November 2014.

- Harrison, Timothy P. “The Battleground.” Biblical Archaeology Review 29, no. 6 (2003): 28–35, 60, 62.

- Weintraub, Pamela. “Rewriting Tel Megiddo’s Violent History.” Discovery Magazine (online). September 30, 2015.

- Yadin, Yigael. “II. In Defense of the Stables at Megiddo.” Biblical Archaeology Review 2, no. 3 (1976): 18–22.

Thank you for sharing your findings that develop my understanding of biblical places and their history.

Thank you, Virgil. As I continue to produce posts from my recent trip to Jordan and Israel, I hope you will find the remaining sites and material of equal interest. Next stop, Jezreel.