Good detectives build a solid case for indictment by gathering all necessary evidence from a variety of sources. Paying careful attention to details can resolve some of the most difficult problems. In the realm of biblical studies, the identification, nature, and use of inscriptions with psalms tends to be passed off as a waste of time, because many scholars just assume that they were added much later than the actual psalm compositions. However, there is much evidence to the contrary. Let’s examine the available evidence.

Biblical Evidence

In the Psalter 116 of its 150 psalms possess inscriptions (or titles, headings). What many Bible readers fail to realize, however, is the fact that psalm inscriptions occur outside the Psalter.

- Psalm 18:Inscription compared with 2 Samuel 22:1. Note these phrases from Psalm 18: “For the choir director” and “A Psalm of David the servant of the LORD” (NASU). First, the musical inscription is first in Psalm 18 and the authorial inscription follows. Neither is found in 2 Samuel 22:1 (which does identify David as author, however). The same psalm, with minor differences in wording in some verses follows these headings. The psalm in 2 Samuel is part of the appendix to the books of Samuel in which evidence is supplied from royal archives regarding the life and work of King David. Psalm 18 was the form of the psalm used in the liturgy of the Tabernacle and the Temple (cp. 1 Chron 16 for David’s involvement in the formation of liturgy for Israel).

- Habakkuk 3:1, 19. The psalm penned by Habakkuk commences with “A prayer of Habakkuk the prophet, according to Shigionoth [unknown meaning; perhaps ‘dirge’]” (v. 1) and concludes with “For the choir director, on my stringed instruments [neginot]” (v. 19). The first verse parallels the second phrase identified above in the heading of Psalm 18, while the end of the 19th verse of Habakkuk 3 parallels the first phrase in the heading of Psalm 18. However, the musical inscription comes at the end of the composition, not the beginning.

- Isaiah 38:9, 20. Hezekiah’s psalm commences with an authorial and historical heading (superscription): “A writing of Hezekiah king of Judah after his illness and recovery” (v. 9). The composition’s final verse reads: “The LORD will surely save me; so we will play my songs on stringed instruments [neginot] all the days of our life at the house of the LORD” (v. 20). Verse 20 could be Hezekiah’s purposeful expansion of the normal musical subscription to such a composition–he incorporated it into the song itself.

- Ezekiel 19:14. “This is a lamentation, and has become a lamentation.” The subscription in this case confirms the introductory instruction in verse 1, “‘As for you, take up a lamentation for the princes of Israel.” It appears to be kind of a historical footnote to the composition, but a subscription nonetheless.

These pieces of biblical evidence all occur outside the Psalter (although 2 Sam 22 is repeated in Ps 18). Therefore, for the sake of consistency, those who choose not to read or include the psalm inscriptions in the Psalter, should not be reading or including the psalm inscriptions outside the Psalter. Why is the Church so inconsistent on this matter in the modern era–both in the pulpit, in commentaries, and in Bible translations? Skepticism. Hermeneutics of doubt. Denial of the integrity, authenticity, and inerrancy of the biblical text.

The New Testament offers its own pieces of evidence in regard to the integrity and authenticity of the psalm headings:

- Luke 20:42 and Psalm 110:Inscription. Jesus Himself spoke the following words: “For David himself says in the book of Psalms . . .” The Lord used the emphatic Greek personal pronoun (autos, “himself”) to certify that the claim of Psalm 110’s inscription is accurate and refers to David’s authorship. The statement of Davidic authorship occurs only in the psalm’s inscription, not in the body of the psalm. Peter later makes the same observation from the same psalm (Acts 2:34-35). By the way, many seek to deny the authorial force of the psalm inscriptions’ “of David.” But, when we consider all of the evidence, “of David” (or “of Solomon,” or “of Moses,” etc.) should be translated “by David.” The same authorial Hebrew lamed preposition occurs in Isaiah 38:9 (“A writing of [by] Hezekiah”), Habakkuk 3:1 (“A prayer of [by] Habakkuk”), and Psalm 90:Inscription (“A Prayer of [by] Moses, the man of God”).

- Acts 13:35-36 and Psalm 16:Inscription, 10. At Antioch of Pisidia the apostle Paul, arguing for the Messiahship of Jesus, refers his hearers to the testimony of the Old Testament. One of the texts that he cites consists of Psalm 16:10 (Acts 13:35. Paul explains how the writer/speaker of Psalm 16:10 could not be speaking of himself, but of the Messiah. Paul identifies the psalmist as David. That detail occurs only in the psalm inscription. On the day of Pentecost in Jerusalem the apostle Peter had cited the same text, made the same argument, and identified the same psalmist (Acts 2:29-32).

Thus, the accuracy, integrity, and inspiration of the psalm inscriptions should not be denied. How many witnesses does it require to establish such a fact? Aren’t the testimonies of Isaiah, Habakkuk, Jesus, Peter, and Paul sufficient? If not, what does that say about the integrity of any of these men? Above all, what does it mean with regard to the deity, truth speaking, and testimony of Jesus Himself? The implications of refusing to translate, to read, or to accept the inspiration of the psalm inscriptions go beyond just questioning the integrity of the psalm inscriptions outside the Psalter. The implications even touch upon the character of Jesus Himself.

Ancient Near Eastern Evidence

Psalm inscriptions occur outside the Hebrew Bible as well as within it. The practice of psalm inscriptions appears in a variety of ancient near eastern materials. This fact has not escaped the attention of scholars dealing with the extrabiblical evidence. Consider the observations Kenton L. Sparks makes concerning Mesopotamian hymns, prayers, and laments:

Our modern attempts to classify the Mesopotamian genres . . . are eased by the ancient tendency to place generic labels in the superscripts or subscripts of the text. The labels sometimes corresponded to musical instrumentation used with the piece, such as the BALAG (harp song), TIGI (bass drum song), and ERŠEMMA (tambourine laments), while others related to the format or purpose of the text, such as BALBALE (antiphonal recitation?), ERŠAHUNGA (lament for appeasing the heart), and ŠUILLA (incantation prayers offered with uplifted hands). Modern scholars are not always sure what to make of these terms, which is not surprising given that the ancients sometimes used the labels rather loosely and imprecisely.[1]

Confirming such ancient near eastern evidence, Yitschak Sefati points to Sumerian love poems from ca. 2100-1800 BC–near the time of the biblical patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob):

As in most of Sumerian poetic works, the following poems are ascribed to their appropriate categories by the ancient poets themselves with a special subscript at the end of the composition, resembling the superscript of the biblical psalter.[2]

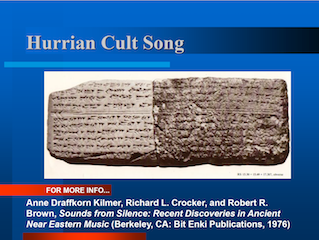

A Hurrian cult song tablet from Ras Shamra (ancient Ugarit) dating to ca. 1400 BC (near the time of the biblical Moses) includes a subscription that reads, “This is a song of the Fall-of-the-Middle, a hymn of the gods, from Urhiya, copied by Ammurapi.”[3] In other words, the ancient near eastern practice of ancient poets including superscriptions and subscriptions for their poems predates the inscriptions on hymns, psalms, prayers, and laments in the Hebrew Bible. It makes no sense at all for biblical scholars to question the authenticity and ancientness of the biblical psalm inscriptions. The Hebrew poets followed many of the same literary conventions as their neighboring cultures.

How ancient are the biblical psalm inscriptions? The meanings of some of the psalm inscriptions’ technical terms were no longer understood at the time of the translation of the Greek Septuagint (ca. 250 BC). For example, the inscription on Psalm 4 in the Hebrew reads, “For the superintendent of music on stringed instruments; a psalm by David.” The Septuagint translators understood it as reading, “Unto the end, in psalms, a song by David.” “For the superintendent of music” (or, “For the chief musician”) was repeatedly misidentified by the Septuagint translators and they also seem to have been guessing about the meaning of neginot (see above under Biblical Evidence) by translating it with the Greek en psalmois. Another example occurs in the inscription to Psalm 46 in which the Hebrew term alamot (most likely “women” or “sopranos”) became “hidden things” (tôn kruphiôn). Such evidence confirms the antiquity of the psalm inscriptions–the meaning of their technical terminology has already been lost by the Hebrew-speaking community by at least 250 BC or before.

Implications

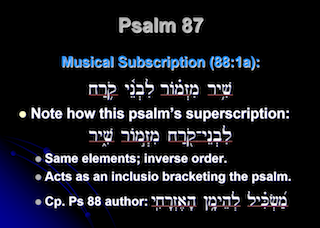

In accord with Thirtle’s theory of psalm titles,[4] musical material should be viewed as subscriptions for the preceding psalm, while the literary and historical materials are superscriptions for the following psalm. An excellent example of this division is to be found in the poem in Habakkuk 3. Such an approach also solves some of the nutty problems involving seeming contradictions in the psalm inscriptions. Just one sample will suffice for our purpose in this brief study: Psalms 87 and 88.

Current Psalm 87 Inscription

A psalm by the sons of Korah.

A song.

Current Psalm 88 Inscription

A song.

A psalm by the sons of Korah.

For the choir director;

according to Mahalath Leannoth.

A maskil by Heman the Ezrahite.

Note that the first two lines (red and blue) of Psalm 87 are repeated in inverse order as the first two lines of Psalm 88. This inverted inclusio emphatically marks off Psalm 87 as the composition of the sons of Korah–the authorial information. Then the typical musical subscription (green) commences with “For the choir director” (see Hab 3:19) and continues with musical instruction (perhaps for the tune?) “according to Mahalath Leannoth.” All of these lines belong to Psalm 87 for its superscription and its subscription. The final line (purple), “A maskil by Heman the Ezrahite,” belongs to Psalm 88 as its literary and authorial superscription. That immediately resolves the apparent conflict in the currently published translations that attributes authorship to the sons of Korah and to Heman the Ezrahite. In addition, Psalm 88 is one of the gloomiest psalms in the Psalter, making a potential mismatch for the tune Mahalath Leannoth that might refer to dancing–a reference more fitting for Psalm 87:7 speaking of singing, flutes (or dancing), and “springs of joy.” Thus, the following pattern provides a more accurate representation:

Note that the first two lines (red and blue) of Psalm 87 are repeated in inverse order as the first two lines of Psalm 88. This inverted inclusio emphatically marks off Psalm 87 as the composition of the sons of Korah–the authorial information. Then the typical musical subscription (green) commences with “For the choir director” (see Hab 3:19) and continues with musical instruction (perhaps for the tune?) “according to Mahalath Leannoth.” All of these lines belong to Psalm 87 for its superscription and its subscription. The final line (purple), “A maskil by Heman the Ezrahite,” belongs to Psalm 88 as its literary and authorial superscription. That immediately resolves the apparent conflict in the currently published translations that attributes authorship to the sons of Korah and to Heman the Ezrahite. In addition, Psalm 88 is one of the gloomiest psalms in the Psalter, making a potential mismatch for the tune Mahalath Leannoth that might refer to dancing–a reference more fitting for Psalm 87:7 speaking of singing, flutes (or dancing), and “springs of joy.” Thus, the following pattern provides a more accurate representation:

Correct Psalm 87 Superscription

A psalm by the sons of Korah. A song.

Correct Psalm 87 Subscription

A song. A psalm by the sons of Korah.

For the choir director; according to Mahalath Leannoth.

Correct Psalm 88 Superscription

A maskil by Heman the Ezrahite.

Conclusion

Bible editors, Bible translators, and commentators[5] alike have perpetuated wrongly divided psalm inscriptions. When properly understood (using Hab 3 for our pattern), the musical subscriptions can be properly identified and moved to the end of the preceding psalm while the literary and historical superscriptions can be kept with the subsequent psalm. The psalm inscriptions are ancient, authoritative, and accurate. The evidence supports their inspiration. We must preserve them, correctly apportion them to their respective psalms, read them privately and publicly, and expound them as we do when they occur in the Old Testament outside the Psalter.

Footnotes

[1]Kenton L. Sparks, Ancient Texts for the Study of the Hebrew Bible: A Guide to the Background Literature (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2005), 85. Sparks indicates that some of those superscripts and subscripts correspond to musical instrumentation and others to the format or purpose of the text.

[2]Yitschak Sefati, “Love Poems,” in The Context of Scripture, 3 vols., ed. by William W. Hallo and K. Lawson Younger (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2003), 1:540-43.

[3]For a full description and explanation of this fascinating tablet, see Anne Draffkorn Kilmer, Richard L. Crocker, and Robert R. Brown, Sounds from Silence: Recent Discoveries in Ancient Near Eastern Music (Berkeley, CA: Bit Enki Publications, 1976).

[4]James William Thirtle, The Titles of the Psalms: Their Nature and Meaning Explained (London: Henry Frowde, 1904). See, also, John Richard Sampey, “Psalms, Book of,” in The International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia, 5 vols., edited by James Orr, 4:2487-94 (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1939), available here online. More recently, see Bruce K. Waltke, “Superscripts, Postscripts, or Both,” Journal of Biblical Literature 110, no. 4 (1991): 583-96. Unfortunately, many evangelical scholars have ignored Waltke’s article as well as Thirtle’s seminal volume In Hebrew Whiteboard all psalms will be divided in accord with the principles demonstrated by this study.

[5]One commentator published his volume with the psalm inscriptions properly arranged in their correct locations as superscriptions and subscriptions: W. Graham Scroggie, The Psalms (reprint, Old Tappan, NJ: Fleming H. Revell, 1973).